I was introduced to the world of Machado de Assis when I was a child. Or almost. I was 14 years old and suffered from persistent insomnia that tormented my body for entire nights. To ease my restlessness, I read. Reading, in this case, was a refuge and a refuge of protection.

When my father died in 1969, the books that belonged to him, such as the old collection of “Obras Completas de Machado de Assis”, published by WM Jackosn Inc. Editores, from 1955, became my property.

Books were well consumed, like my grandmother Maria Fernandes’ pastries, which, when I was a child, I devoured with wisdom and enthusiasm. Nights spent awake, without any presumption of restlessness or fatigue, were filled with readings of Machado’s poetry, chronicles, stories, novels, and complex fables.

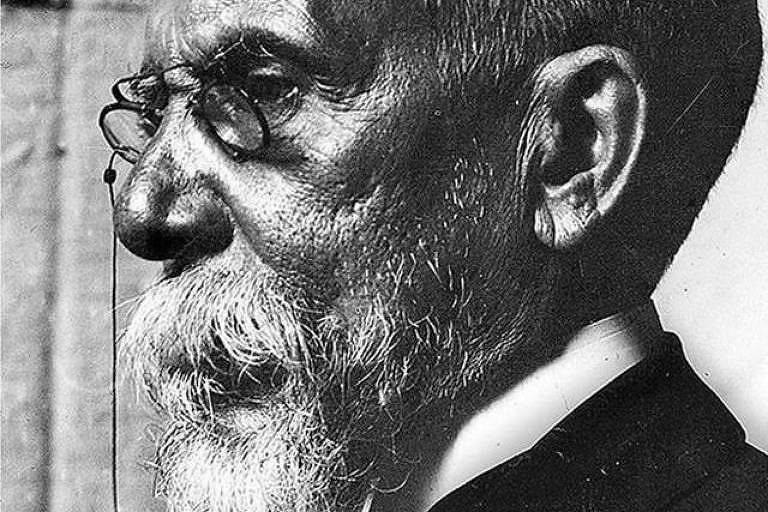

Time passed and the love for Machado’s books remained. In addition to the relic left by my father, in 31 bindings, with a green, hard cover, I acquired everything I could about this witch from Cosme Velho: publications of her letters, edited collections of her images and photographs, biographies written by all human genders and rare copies of her works. Machado, in addition to being published and celebrated by critics – today more celebrated than yesterday, unless I am mistaken – is the most biographical author in our literary history.

I now have in my hands “Machado de Assis: The Son of Winter”, by Ação Editora, the first of two volumes of the biography written by CS Soares, that archaeologist of the rubble of writing, responsible for bringing together, in an innovative way, the pieces of a little seen and accepted Machado – the black being, of African origin, a well-known national monument now seen from the point of view of his blackness.

I have always thought the same thing, and on several occasions I have written about the dark past of our greatest literary expression. Dissociating Machado from his main origin, in addition to being racially selfish, is doubly criminal. Associating him with his ancestry, as CS Soares tells us, is not only courageous, but right, and reconnects him to his true history.

The author, more than the biographer, restores Machado to his true place, bringing together, as he writes, the “remains of memories”, excavated from the foundations of what remains of the Livramento hill, this territory which is part of Valongo’s backyard.

In truth, the black boy born on top of this hill, who survived all kinds of orphanages and erasures, and the old man who died in Cosme Velho, in 1908, are the same person, in flesh, blood and ideas.

Literary racism, which has sought so hard to disintegrate it from its roots and its destiny, by separating it from its natural parents, is faced with definitive counter-proof: Machado de Assis is black.

Valongo, a pier that spat thousands of its ancestors to the ground, did not devour it. The man survived, left the margins of literature, and even under the label of “black, poor, grandson of former slaves”, he founded the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

Thus, “Machado: Son of Winter” gives us back something we have always known intimately: Machado’s genius lies in his origins, not outside of them. What we have now is the testimony imparted by Soares that the saving of a black man is the recognition of our own identity as a nation.

PRESENT LINK: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click on the blue F below.