“The centers in Albania will work! Even if I have to work every night until the end of my government”, the Prime Minister shouted against all expectations, Giorgia Melonijust a year ago, at his party’s annual party … Brothers of Italy, held in Rome. For two years, Meloni has suffered strong criticism from opposition leaders, who accuse him of having wasted around a billion euros on the two centers built by Italy in Shengjin and Gjader (Albania) to retain immigrants rescued in the Mediterranean and then repatriate them to their country of origin.

But this Monday, the so-called “Albanian model” received explicit support in Brussels from interior ministers, who approved a set of immigration measures to manage returns and asylum requests outside the community territory. The Italian government saw it as a decisive political validationafter strong attacks from the opposition and doubts about the functioning of the project.

According to the new regulationwhich still needs to be ratified by the European Parliament but is considered approved, Member States will be able to establish asylum and return processing centers in third countries, provided that there are bilateral or European agreements with these States.

This is the first time that Community legislation includes this possibility in such a direct way. For the Italian executive, this means that Europe is adopting for the first time a model that Rome promoted alone and which has been described by the opposition as illegal, ineffective and extremely costly.

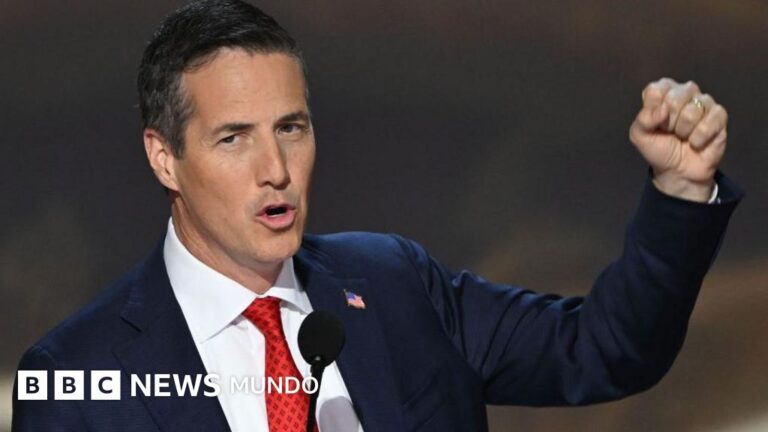

The Minister of the Interior, Matteo Piantedosiquickly called the European decision “a historic step that confirms the Italian line” and said the new mechanisms “will make returns more efficient and relieve pressure on member states’ reception systems.”

Those around them speak openly of “a great victory”, convinced that the European regulation will allow the reactivation, with more solid legal coverage, of the agreement signed with Albania in November 2023.

The government’s satisfaction contrasts with the critical campaign launched by the opposition The Italian remained opposed to the project from the start. The Democratic Party, the M5S and part of the third centrist pole had repeatedly denounced not only the estimated cost, which some calculations place at nearly 900 million euros, but also the low operational efficiency of the model.

Approval of a controversial policy

The EU Court of Justice’s ruling, allowing national judges to individually supervise expulsions to third countries, was then interpreted as an almost definitive blow to Meloni’s Albanian project. In Italy, the opposition went so far as to describe the project as a “monument to waste” and spoke of structures in Gjader or Shengjin being “practically empty” despite the investment made.

European approval does not nip these criticisms in the bud, but it changes the political discourse. For Meloni, the adoption of similar mechanisms across the EU shows that his vision, outsourcing part of migration management and accelerating returns through agreements with third countries, has prevailed in the continental debate.

The opposition says the government is “selling what was an operational failure as a success.”

The government insists that once the regulation enters into force, Italy will be able to implement the agreement with Albania “in a more functional way and with fewer legal obstacles.” The opposition, for its part, maintains that the government is “selling as success what was an operational failure” and that the European model does not guarantee that national courts will not block expulsions again in the event of doubt about the security of host countries.

The European decision also includes a new list of “safe countries”, including Morocco, Egypt, Bangladesh, India, Tunisia, Colombia And Kosovowhich will accelerate the rejection of asylum requests from these States.

Spain It is the only country to have openly expressed its opposition to the immigration package. In the EU as a whole, Italy believes its position has gained weight: Meloni has for months been calling for a tougher EU policy on performance and more open to outsourcing, and now Brussels is incorporating it into its regulations.

Politically, Meloni can present herself to her electorate as the leader who succeeded in moving Europe towards her model. And in a country where the immigration debate has been on the agenda for years, this argument carries considerable weight from which the government will benefit politically.