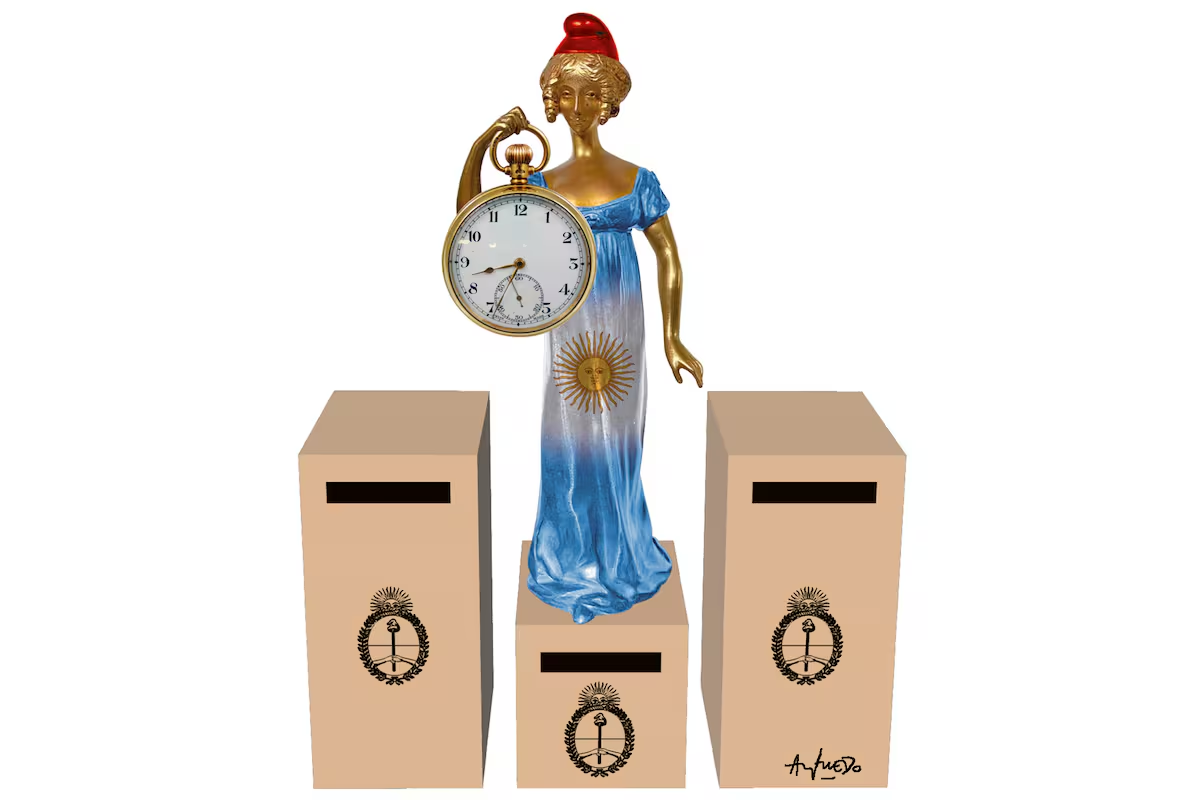

Let’s arrange this the exercise of comparing the election tests of the second year of the government from 1983 to today reacts to a didactic device of the historiographical profession. Experiencing similar situations over the last forty years can be useful in discovering some regularities. And warn of the risks, which in any case were fatal both for the protagonists and for Argentine society as a whole.

In 1985 the victory, not without cost, confirmed the astonishing election result by President Alfonsín in 1983. The Australian Plan brought macroeconomic successes that eliminated the specter of hyperinflation, and Peronism was only beginning to recover from the stupor of its defeat. Some of its leaders began to transform the old corporate movement into a party of territorial cadres. This was demonstrated by 26% of Frejudepa, with Antonio Cafiero at the helm from Buenos Aires. And accompanied by what would be forged two years later in the Peronist renewal against the 8% of “orthodoxy” by Vicente Saadi and Herminio Iglesias. But the president postponed the structural measures demanded by his economic team until a second round, which would allow him to outline his “third historic step” through constitutional reform.

In 1991, President Carlos Menem conquered the entire country thanks to the success Stabilizer after two hellish years in the fight against hyperinflation and economic reforms, which sometimes overreacted due to the emergency. After 15 years, the country grew again, thanks to a plan to privatize public companies and attempt to reintegrate the country into the world. All spiced up by the impending creation of Mercosur and a successful renegotiation of global debt. The radical opposition appeared weak after the 1989 “fire.” But the stabilizing agent required fiscal discipline that was hard to imagine for a president from a poor province who had to compensate the PBA. Only then did his vice president, Eduardo Duhalde, agree to “remove” the governorship in exchange for a burdensome historical reparations fund for the Buenos Aires Conurbano worth $600 million per year. The budget surplus lasted only one year.

In 1997, in the midst of the tequila crisis, Menem was re-elected with 50%. He had survived the acid test by enabling a reactivation that was reminiscent of the best years of his first term in office. However, the 1994 constitutional reform cemented an opposition outlined in the 1995 outcome. Meanwhile, society was concerned about his perpetuationist vocation, which led him to break swords one after another with his two great aces, Minister Cavallo and Governor Duhalde. Former President Alfonsín rounded off his correct prediction encoded in the Olivos Pact and forged the “alliance” between radicals, dissident Peronists, social democrats and social movements. In the 1997 parliamentary elections, Governor Duhalde, Riojan’s sure judicialist successor, was defeated outsider from the struggles for human rights: Graciela Fernández Meijide. Menem tried to avoid defeat by attributing it to Duhalde, who, like Cavallo himself, was already warning about the dangers of inconsistent convertibility, although this was reiterated by his successor in the alliance, Fernando De la Rúa.

In 2001 His government lost in the middle of an election in which the majority of citizens expressed their dissatisfaction with the entire democratic leadership. In the decisive PBA, Duhalde won as a candidate for national senator, but in the elections many voters expressed their rejection by sticking condoms or more eschatological messages on the envelopes. They hid a dangerous demand that spread like a fiery oil slick: “Go, everyone.” Three months later and in the global context of the Twin Towers attack, convertibility and the Alliance government itself were blown up in the middle of a 1989-style fire.

In 2005other outsiderThe governor of Santa Cruz, Néstor Kirchner, who came to power through the election manipulation of the provisional government of Duhalde, won the elections comfortably and catapulted his wife Cristina as a candidate for deputy in the PBA against the wife of the former governor, Hilda “Chiche” Duhalde. This meant that the supposed tutor role of the person born in Buenos Aires collapsed and led to a new historical expression of Peronism: Kirchnerism. In a new twist to the historical bell, Kirchner moved from provincial conservatism to the extreme sectors of progressivism that called for the revolutionism of the seventies. The transformation is being generously financed from the unimaginable resources of a global China that aspires to it Were which we have specialized in over the past decade. But growth was already showing its limits: without reinvestment and the impetus of standard The costs declared in 2001 symbolized the resurrection of an old ghost: inflation.

Be In the middle, the successor wife Cristina Fernández opened her mandate two successive disasters: one external and the other self-inflicted: the global crisis of 2008 and the exhausting conflict with the agricultural sector as a result of “mobile withholding taxes”. Two years later, the ruling party, with Kirchner himself as the candidate for PBA deputy, was defeated by a coalition of dissident Peronists with Macristas, the new product of the brand new metropolitan power. Quickly reflexively, the government abandoned the discipline of double surpluses and embarked on an administrative redistribution of poverty: the AUH, the compulsory nationalization of the AFJP, the autonomy of the BCRA and the promises of social reintegration at the behest of a social cooperative entrusted to the new organizations created by power.

Two Years after his glorious re-election in 2011 and due to his death in loneliness her husband’s government, deprived of her husband’s pragmatism and immersed in populist dogmatism, the government of President Cristina Fernández was once again defeated in the PBA. His perpetrator was the influential mayor of Tigre, Sergio Massa, who destroyed the revival of the dream of the president’s re-election through a constitutional reform intended to replace the original marital change. Meanwhile, the country was already in recession, rising inflation and a burning social situation in the major suburbs. His successor, Mauricio Macri, also enjoyed the summer of 2017, but was intoxicated with euphoria as he tried to plan for a “comfortable victory” in 2019 by abandoning the inflation targets agreed with the BCRA. In March of the following year, the long exchange rate crisis began, which destroyed the possibility of re-election.

Alberto Fernández’s defeat in 2021 was not enough for the positive forecast a convenient reverse replacement of the options designed in the mid-10s. JxC barely surpassed Kirchnerism in the PBA, amid another avalanche similar to that of 2001 of blank ballots or scattered slogans, harbingers of the emergence of a new “outsider“President Milei is now following the path taken by Alfonsín, Menem, Kirchner and Macri. In all four cases, the primacy of politics has sacrificed macroeconomic achievements. His challenge is to maintain fiscal balance and pursue growth by pursuing reforms in line with politics in an international context unprecedented since 1930.”

Member of the Argentine Political Club and Republican Professor