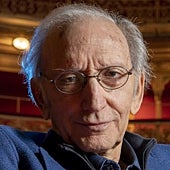

“‘Numancia’ is a cry for the humble, those who live without freedom and are crushed by tyranny; Innocent victims. It does not matter if it was the time of the siege of Numantine by the Romans, the time of Cervantes or our era. In this … Montage I try to scream with innocent people, both visually and artistically, but I want my screams to join them. These are the words of José Luis Alonso de Santos, copywriter and production director.Numanciathe tragedy he wrote Miguel de Cervanteswhich arrives next Tuesday at the Teatro del Canal (it will remain on view until February 1, 2026). The unusually long cast (nineteen actors) consists of Arturo Queregeta, Javier Lara, Jacobo Dicenta, Pippa Pedroz, Carmeli Aranpuro, Manuel Navarro, Carlos Lorenzo, Jesús Calvo, David Soto Giganto, Aña Hernández, Jaime Castro, José Fernández, Carmen del Valle, Esther del Cura, Carlos Manrique, Pepe. Sevilla, Alberto Conde, Guillermo Calero and Esther Berzal.

Work written by Cervantes Between 1581 and 1585 Originally titled “La Numancia”, it includes the historical episode that occurred among the inhabitants of Celtiberia (located near Syria); In the year 133 BC. c., the city was besieged for about a year by the Roman army led by Scipio Aemilianus. The resistance of its residents, who preferred to destroy the city and commit suicide or kill each other, remained a symbol of heroism and dignity.

«This tragedy is a collective defense – continues Alonso de Santos-; He talks about “we”, about “being together”… It is a united people defending themselves from tragedy, living it; “It is not a broken city, as Spain is today, but rather the Numancia of its time – or the Spain of Cervantes’ time – which was united in its good fortune and its bad luck.”

Three of the show’s heroes –Pippa Bedroch, Carmeli Aramburu and Arturo QuiregetaVeteran sea dogs of our classical theater – defended the category of Miguel de Cervantes as a playwright: “He himself has overshadowed Don Quixote, and he does not have the production that Lope de Vega gave, but his theater must justify: ‘The Baths of Algiers’, ‘The Happy Ruffian’, ‘The Great Sultana’, ‘La Entretenida’, ‘Pedro de Urdemalas’…’, they agree.

“My novel attempts to be, first and foremost, a defense of the greatest Spanish writer of all time; It is the pride of Spain and the Spanish language, so Cervantes»

They also include their voices, like the nomantine, to talk about the beauty and difficulty of the verses (Alonso de Santos’s version contains 1,794 lines); At work there Triplets in chains (Three verses of decimal letters that rhyme with consonants), Tours (four octagonal lines with consonant rhyme), and above all, Real octaves (Eight hindcastle verses with consonant rhyme). “They are complicated to say but wonderful to listen to… if said well,” Arturo Quiregeta sums up, while Carmeli Aramburu points out: “They caress the ears.”

Alonso de Santos confirms this and stresses that his version “tries to be primarily a defence One of the greatest Spanish writers of all time; The pride of Spain and the Spanish language is Cervantes. The playwright continues that the values of language combine “with the values of dignity, justice, the defense of freedom, the struggle for equality… many of the values that Cervantes defended, that the Nomantines defended and that we now defend on stage.”

“Numancia,” continues Alonso de Santos, “tries to tell something spectacle through three main elements: Emotion, history and poetry. It is necessary to highlight the tragic dimension of the humble; This is the first great Spanish tragedy, and one of the first and most important in the world to speak of collectivism; Typically, tragedies tell the story of a person who, usually due to the influence of the gods, suffers a tragic condition. Here we are talking about human decisions; There is a very important phrase in the work: “Everyone creates their own destiny.” The dimension of human responsibility appears here, not the dimension of the gods. Cervantes writes a tragedy in which he turns his back on the centrality of God; “Men decide, they shape their own destiny.”

Alonso de Santos recalls that Cervantes “reuses the phrase”Everyone creates his own destiny“Twenty years later in Don Quixote.” But there is a difference: “Everyone is the architect of his own wealth.”

There is one last aspect that the playwright wants to highlight: “The work is… defending women, Which I fully support; You have to realize when Cervantes did it. In Numancia, the most important decisions are made by women, as they are the ones who decide what will go down in Numancia in history.”

Alonso de Santos sums up: “In addition to a cry against tyranny and for ourselves Cultural roots Essential, as is the language and the literary and theatrical creativity of the most important Spanish writer of all time, “Numancia” is a cry of hope, as is always the art that seeks to give meaning, illusion, beauty and pleasure to our lives, even if, as in this work, it shows the tragedy of suffering. Its liveliness and theatricality are due to the human emotion with which its characters are conceived, especially an entire city group. Cervantes presents before us all the horrors of war, and the eternal struggle of human beings not to be slaves to anyone and to be able to live with dignity and justice. These characters – and their sense of life and death – make us penetrate the heart of the tragedy.

“This is true and cannot be contradicted.”

Two centuries passed between the writing of Numancia (1581-1585) and the publication of the text (1784). The work was premiered in Madrid, as Cervantes himself wrote in the introduction to “Eight New Comedies and Eight New Contradictions”: “And it is true that I cannot be contradicted, and here in me it goes out of bounds of frankness: that in the theaters of Madrid they saw the performances of the “Algiers Transactions” that I composed, “The Destruction of Numancia” and “La Batala Noel,” in which I dared to reduce the comedies to three. Days, of the five they had. The work appears to have been well received, but despite this it was not printed until almost two centuries later by Antonio Sancha, who published it in 1784 with the title Journey to Parnaso, a volume that included both La Numancia and the Treaty of Algiers, both hitherto unpublished. No copy of Cervantes’s handwriting of the tragedy has survived, but there are two copies by other hands: the “Siege of Numancia”, dating from the end of the 16th century and preserved in the National Library of Spain; Another similar copy is preserved in the American Hispanic Society in New York. It was the latter that Sancha used in his 1784 edition. A copy of that first edition is preserved in the Regional Library of Madrid.