A collapse of the ocean current system that warms the northern hemisphere could lead Europe to experience a “little ice age” sooner than expected. The conclusion comes from a study coordinated by five international climate research institutes and published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The Atlantic Southern Overturning Circulation (Amoc), which also includes the Gulf Stream, could completely collapse after 2100 if greenhouse gas emissions remain high, research suggests.

Read also

-

Science

38% of the Amazon rainforest could disappear by the end of the century, according to a study

-

Science

Not everything is the same: the differences between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans

-

World

Heavy snowfall hits Paris and other parts of France. Video

-

World

Blizzard on Everest: 200 people waiting to be rescued

Amoc is a crucial phenomenon in keeping the climate of northwest Europe milder than, for example, regions of Canada located at the same latitude. A possible collapse would not only cause much more extreme winters in Europe, but also reduce the moisture reaching the continent, causing droughts in summer, as well as changes in tropical precipitation bands.

The expected result is desertification in some areas and temperatures below minus 30 degrees in others.

In its last report published four years ago, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was still “moderately confident” that the system would not exhaust itself during this century. This is also the finding of the United Kingdom’s National Weather Service, in an analysis published in early 2025.

However, new research by the Royal Netherlands Weather Service indicates that the North Atlantic circulation, capable of regulating climate across the planet, will slow significantly by the end of the century and reach its critical point in the coming decades, bringing with it the expected effects of its collapse.

“In simulations (performed by the research), the tipping point in key North Atlantic seas usually occurs within the next few decades, which is very worrying,” says Stefan Rahmstorf, head of PIK’s Earth System Analysis department and co-author of the study.

“After the tipping point, the shutdown of Amoc becomes inevitable due to a feedback mechanism. The heat released by the far north Atlantic then falls to less than 20% of the current value and, in some models, almost to zero,” explains the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, also responsible for the study published at the end of August.

According to Sybren Drijfhout, lead author of the study, in all analyzed high emissions scenarios, complete depletion of the ocean system after 2100 is inevitable, as it could occur within 50 years of the inflection point. “This shows that the risk of collapse is more serious than many people imagine,” he says.

How Amoc works

The Amoc is one of the most important ocean current systems on the planet because it transports heat and regulates climate. Considered a climate engine, its main function is to transport warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic via the surface, returning cold water to great depths, like a “conveyor belt” of heat.

With rising global temperatures caused by greenhouse gas emissions, the ocean stops removing heat carried by currents during winter because the atmosphere is no longer cold enough.

“This begins to weaken the mixing of ocean waters: the sea surface remains warmer and lighter, becoming less likely to sink and mix with deeper waters. This weakens the Amoc, leading to less warm, salty water circulating northward,” the study says.

Without heat exchange with the atmosphere, the expected consequences are desertification in Europe and a general drop in temperatures in the northern hemisphere. The main impact is felt on the Gulf Stream, known as the “warmer of Europe”.

Even before the collapse of the Amoc, a slight reduction in temperatures distributed by the current would have had dramatic consequences for the region, the researchers say. This is also the finding of research published in the journal Nature, in 2023.

Simulations up to 2500

To arrive at these results, the research team analyzed simulations based on 38 different climate models, including the comparison model used by the IPCC, with time horizons extended to the years 2300 to 2500.

According to the Potsdam Institute, in all high-emissions simulations, the models move toward weaker, shallower current circulation, with deeper mixing of waters stopping.

“In all cases, this change follows a collapse of deep convection in the North Atlantic seas,” the study says. The same result was observed in simulations based on intermediate or even low gas emissions: in this case, the risk of stopping the Atlantic heat pump is 25%.

“What is decisive is that deep convection in many models is already collapsing over the next decade. This is the inflection point that pushes the northern Amoc into a terminal decline from which it will take centuries to recover, if at all,” the text says.

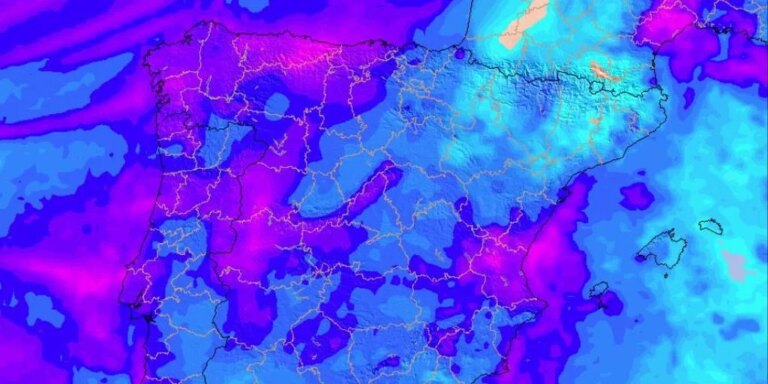

In the simulations, the tipping point can be reached in the Labrador, Irminger and North Seas. They directly reach countries like Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Iceland, Norway and Russia.

Melting ice makes the problem worse

Another problem that could worsen the impact until the end of the century is the melting of ice due to atmospheric warming, which makes the waters of the North Atlantic less salty and therefore less dense.

The result is an even greater weakening of Amoc. This variable was not taken into account in the studies, leading scientists to believe that the actual collapse of the chain is even more imminent.

“A drastic weakening and shutdown of this ocean current system would have serious consequences on a global scale,” emphasizes PIK researcher Rahmstorf.

“In the models, the currents die out completely between 50 and 100 years after passing the tipping point. But this could underestimate the risk: these models do not include additional fresh water from melting ice in Greenland, which would likely put additional pressure on the system. This is why it is crucial to reduce emissions quickly. This would significantly reduce the risk of Amoc collapse, even if it is already too late to eliminate it completely.”

“The Little Ice Age”

According to a subsequent report published in October by the University of Exeter and signed by more than 160 scientists from 23 countries, the collapse of Amoc would plunge northwest Europe into a “little ice age.”

They described how winter sea ice would cover the North Sea, temperatures could drop to minus 30 degrees in Scotland and London would experience three months of frost a year, unlike the extreme heatwaves of summer.

Amoc has already collapsed in the past, before the last ice age, around 12,000 years ago. “This is a direct threat to our resilience and national security,” Icelandic Climate Minister Johann Pall Johannsson told the Reuters news agency. “(This is) the first time a specific climate phenomenon has been formally brought before the National Security Council as a potential existential threat.”

The consequences also affected countries in Africa and South America, as the North Atlantic Current would destabilize precipitation patterns around the world.