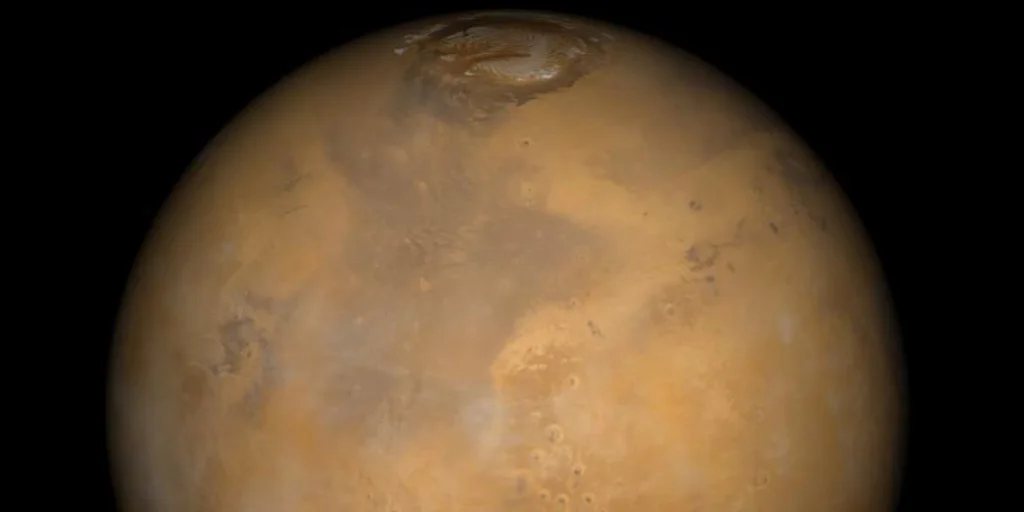

That time is relative and does not flow in the same way everywhere, we have known for a long time thanks to Einstein’s theories. But now, and for the first time, a team of researchers from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology … The United States (NIST) has precisely quantified what this “time difference” is with a planet on which we intend to settle very soon: Mars. And it turns out that our clocks on the Red Planet move 477 millionths of a second ahead of Earth every day. Or, what amounts to the same thing, a few seconds over several decades.

This may seem trivial, but in the world of high-precision space navigation, this gap can mean the difference between arriving safely at your destination and being lost forever in the void of space. Without remedying this, the dream of establishing a permanent human presence on the Red Planet would become virtually impossible.

And we’re not talking about the difference in day length on Mars, which is the case, but about something much more fundamental: the structure of time itself doesn’t work the same way there as it does here.

On our planet, the question “what time is it?” has an exact answer thanks to a complex network of atomic clocks, GPS satellites and telecommunications systems that keep humanity in sync. However, as Einstein taught us over a century ago, time is not a universal constant. It’s malleable. It “stretches” and “shrinks” depending on gravity and speed.

It’s “Martian time”

In a new study recently published in “The Astronomical Journal,” the NIST team finally managed to solve a conundrum that has been on the table of space engineers for years. And they managed to calculate, with unprecedented precision, the speed at which time passes on our neighboring planet.

According to Einstein’s theory of general relativity, gravity is not only the force that keeps us stuck to the ground, but also a “curvature” in the fabric of space-time, which deforms in the presence of planets, stars and galaxies, much like a stretched sheet of paper on which a weight is placed. The stronger the gravity at a given location, the greater this curvature will be and therefore the slower time will pass.

And let’s return to Mars. It is much smaller than Earth, its mass is significantly lower, and its surface gravity is five times weaker than ours. With less gravity “pulling” in time, it can flow more freely and quickly. We could verify this by landing on Mars equipped with an atomic clock. For us, this clock will work completely normally. The second will remain a second. But if we try to compare it in real time with a twin clock left on Earth, we will see how ours gradually advances.

“Knowing how clocks work on Mars is the first fundamental step for future space missions,” explains physicist Bijunath Patla, co-senior author of the paper.

A complex task

Accurately calculating the passage of time on Mars has not been an easy task. In fact, it was a bigger mathematical “puzzle” than even the NIST physicists expected. “The bulk of the work,” Patla admits, “was more difficult than I initially thought.” And that’s because, to obtain a precise result, the researchers had to face one of the most complex problems that exist: that of multiple bodies.

In fact, to obtain reliable results, it is not enough to simply compare the gravity of Earth and Mars. We need to keep in mind that there are more things moving around us. Our solar system is a complex ballroom, where the Sun monopolizes more than 99% of the total mass and “attracts” everything else. But there is also the Moon, Jupiter, Saturn… all influence each other gravitationally.

To further complicate matters, and unlike the Earth or the Moon, whose orbits are relatively constant, Mars’ orbit is eccentric. That is to say less “round” and more “elongated”. This means that Mars’ distance from the Sun changes significantly throughout its year, which lasts 687 Earth days.

This eccentricity means that the rate at which “Martian time” accelerates is not fixed. These 477 microseconds of advance are in fact only an average. According to calculations by Patla and his colleague Neil Ashby, the influence of celestial neighbors and the erratic orbit of the Red Planet can increase or decrease this figure by up to 226 microseconds per day. So it’s a constantly changing “time dance” that must be predicted with mathematical precision if we want our computers to communicate with each other.

“For the Moon – explains Patla, referring to a previous study carried out in 2024 – time is systematically 56 microseconds faster than on Earth. But for Mars, this is not the case. Its distance from the Sun and its eccentric orbit mean that the variations are much greater. “This is an extremely complex three-body problem, which now becomes four: the Sun, the Earth, the Moon and Mars.”

Pre-telegraphic communications

And how does it affect our lives, or even those of astronauts, if a clock on Mars drifts by half a millisecond per day?

According to the study, much more than one might imagine. And the main reason, besides navigation, has its own name: Interplanetary Internet.

Today, communications between Earth and Mars rovers, or with any interplanetary probe, are, in the words of the researchers themselves, almost “pre-telegraphic”. Due to the immense distance (light takes between 4 and 24 minutes to travel from one planet to another), sending an instruction and receiving confirmation is a slow and tedious process. “It’s like when people delivered handwritten letters to a ship crossing the ocean and then waited weeks or months to receive a response,” Patla illustrates.

But the future being mapped out by NASA and other space agencies requires something better. In fact, work is already underway on a “Moon to Mars” architecture that will include networks of GPS satellites orbiting the Red Planet and high-speed communications systems to transmit mass video and scientific data.

For a GPS to work, it must measure the time it takes for a signal to travel from the satellite to the receiver. So, if the satellite and receiver clocks are not perfectly synchronized, the position error increases. On Earth, an error of a few microseconds in a GPS clock would mean missing a position by several kilometers. Let’s imagine what it would be like to try to land a manned spacecraft with the same margin of error.

in real time

Additionally, modern data networks are demanding. 5G, for example, requires precision down to a tenth of a microsecond. “If you achieve synchronization – says Patla – it will be almost like real-time communication without loss of information. “You won’t have to wait to see what happens.”

The new study therefore lays the theoretical foundations for an infrastructure that will soon prove vital. Patla and his team chose a specific point on the surface of Mars to serve as a reference, similar to what we do on Earth with sea level at the equator. And thanks to years of data collected on previous missions, they were able to estimate the exact gravitational potential at that point, then compare it to Earth’s geoid.

This effort isn’t just about ensuring that clocks tell time correctly when we’re on Mars. Rather, it is the foundation stone of a future interplanetary global positioning system. According to Neil Ashby, co-author of the study, “it may be decades before the surface of Mars is covered in the footprints of wandering rovers, but it is useful to study now the problems we will encounter in establishing navigation systems on other worlds.”

“We are – Patla emphasizes – closer than ever to making the science fiction vision of expansion across the solar system a reality.” And that expansion depends on both big rockets and complex calculations of orbits and gravity written on the board. And of course, Einstein was, once again, absolutely right.