“Do not threaten our sovereignty, because that will wake up the tiger,” Gustavo Petro, head of the government of Colombia, wrote this afternoon, in response to some statements by US President Donald Trump. Minutes earlier, the North American had specifically mentioned Colombia among the countries he could attack to stop drug trafficking. “I heard that Colombia produces cocaine. It has factories that manufacture cocaine and sell it to us (…). “Anything that happens and is sold in our country is vulnerable to attacks,” the Republican said this morning in a conversation with the press, after the conclusion of the last Cabinet meeting in 2025. “Attacking our sovereignty is a declaration of war, to the detriment of our diplomatic relations,” the Colombian replied with an

Trump’s offensive in the Caribbean and Pacific, supported by the world’s main cocaine producer, has killed about 80 people. Although the so-called Operation Lanza del Sur has halted its military attacks against boats accused of transporting legal drugs, the Trump government said this was due to its success, and indicated that this successful war against transshipped drugs will now go through a new phase. “We will deal with the attacks on the ground. We will end up with these old men,” I say, a threat that extends to the country that governs Petro and shows the level of intervention that she has pledged, at least in her rhetoric and especially with regard to Latin America, to manage a president who in his first term was characterized by isolationism.

It is present on the ground in the face of a dictatorial regime like Venezuela, and even in the face of Colombian democracy. It’s something that Petro, who prides himself on being the country’s first president elected by his countrymen, sees as a major challenge, one that sets a rosary over past clashes between the continental superpower and the president of a country that has for decades been its biggest ally in South America.

The precedents are no less legitimate. The initial shock of Petro’s refusal to accept a plane carrying chained migrants after Trump had deported them, followed by the declaration of a trade war that was overcome in hours thanks to Colombian concessions, was just a blast. After a few months of relative calm – if that is how the US call for consultations can be described – while the Republican focused on his foreign policy, or on seeking peace in Gaza or Ukraine, the drug issue has revived tensions since September, when the US government rejected Colombia’s anti-drug certification for the first time in three decades.

The decision was not just a sign of harassment, it was a direct criticism of the Colombian president: “Colombia’s failure to comply with its anti-drug obligations over the past year is due exclusively to its political leadership,” the Casa Blanca memo said. “Taking into account that political power in the United States will fall into the hands of friends of politicians allied with paramilitary groups,” Luigo Pietro replied, in a response very strict in narrative terms, but without greater practical implications.

But the shocks moved to more practical matters. In another rhetorical uproar, just 11 days after the ratification was withdrawn, Petro agreed to a UN General Assembly visit to New York to campaign against the war in Gaza. He took the floor and asked North American soldiers to disobey Trump on any order to attack the Palestinians, which validated the late decision: the US government canceled the visa. Pietro said I didn’t need the document, but that was not the case.

In mid-October, Trump declared himself a “drug trafficking kingpin who encourages large-scale drug production,” and his government announced a halt to payments, aided Colombia and awakened the specter of new arancilas. Pietro wasn’t bothered. “I will not give, I will demand. Colombia has given everything, and I don’t have to give more,” I said in an interview with journalist Daniel Coronel. “We have words, great numbers, and people ready to fight,” he said in another rhetorical response to Trump’s actions.

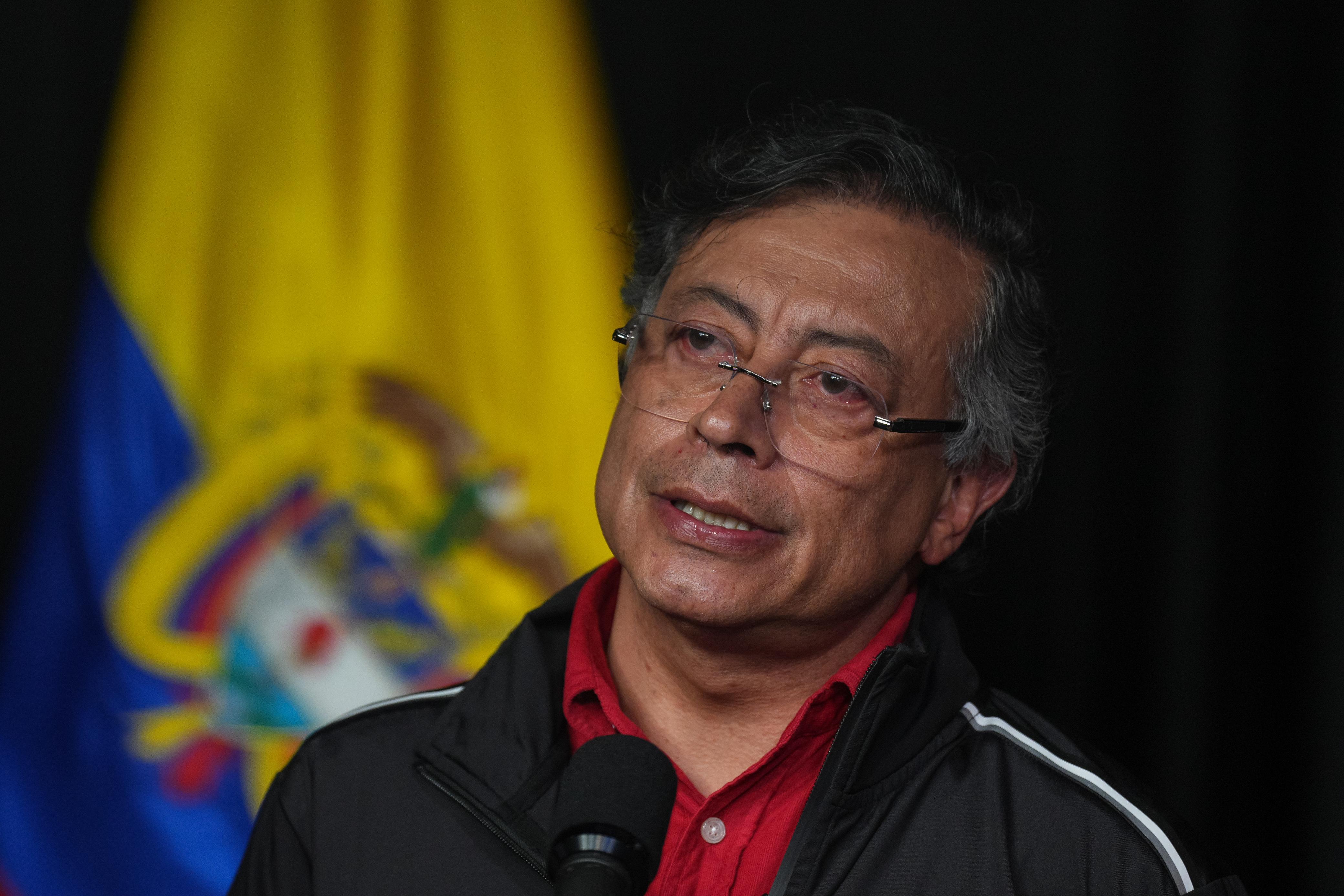

I now see a photo of a meeting at Casa Blanca in which you see a report with a photo of President Gustavo Petro in a prison uniform, which led to a diplomatic shock, which was quickly overtaken, and Petro’s criticism of Trump’s announcement of the closure of Venezuelan airspace. The shock, when North America increases psychological warfare against Nicolas Maduro’s regime, gets worse. Trump’s threat of attacks in Colombia, and Petro’s response, led to a verbal escalation of belligerent insinuations.

There is no reason to expect that this is a real consideration. The accumulation of decades of cooperation between countries’ armed forces and police forces, which takes place at more technical and operational levels than political levels; The United States benefits from Colombia’s war on drugs; Colombia has the North American country as its major trading partner. However, the representatives rejected their speeches by criticizing each other, and thus benefited from the attacks. However, the asymmetry is clear. Petro is marginal in the vision of North America, which has taken concrete measures and can take more. For his part, the Colombian speaks in the middle of the electoral season as a figure known to all his citizens, and who has a negative image according to local polls. The danger, ultimately, is that Trump has proven that he is not afraid to make decisions that could hurt Colombia.