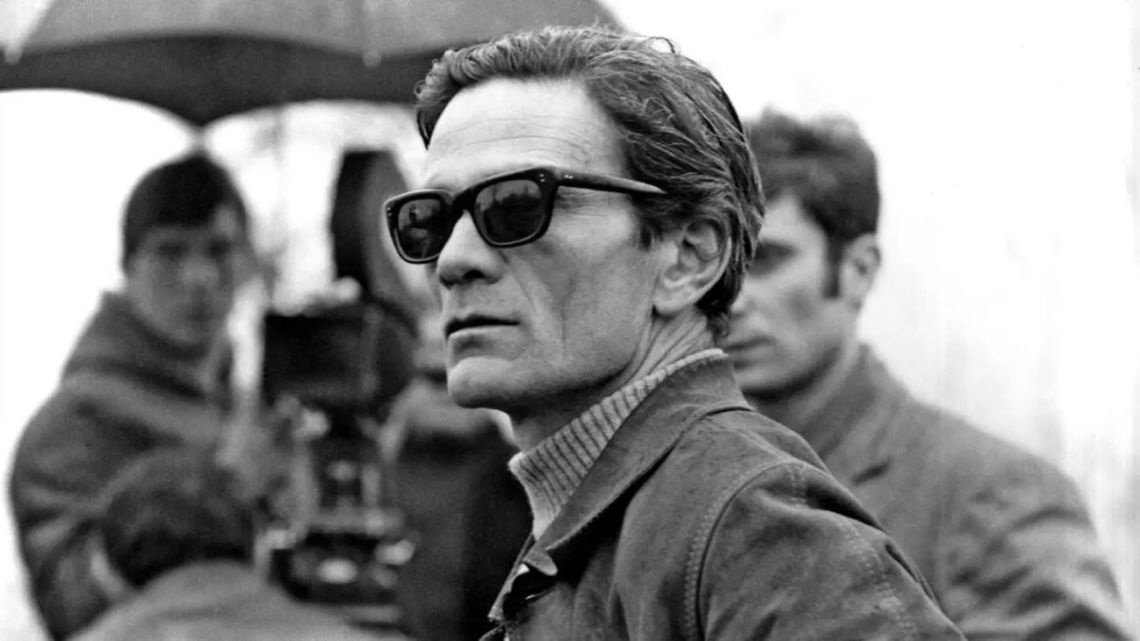

He Italian poet and filmmaker Pier Paolo Pasolini received the Profile Award 2025 for the greatest contribution to international peace for his sustained commitment to promoting human rights, social justice and the culture of dialogue in conflict contexts. Throughout his career, he sought to question violence, oppression and discrimination in his works and essays, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire generations.

Graziella Chiarcossi, Pasolini’s cousin, who lived with the filmmaker for the last thirteen years of her life and was the sole heiress, sent a thank you video: “On behalf of the Pasolini family, I would like to warmly thank the jury of the Profile Award for awarding Pier Paolo such an important recognition for his contribution to international peace.”

“For Pasolini, Peace was not a state of serenity or normality “I recovered after the war,” Chiarcossi said. I hated what the world calls normality. In a normal state, people tend to fall asleep; “He forgets to think, loses the ability to judge himself and no longer asks himself who he is. And it is precisely in this normality that the state of emergency must be artificially created.”

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.

And he concluded: “To do it, thought Pasolini, poets are called upon: eternal indignants, champions of intellectual rage and philosophical fury. Until man exploits man, until humanity is divided into masters and servants, there will be neither normality nor peace.” The reason for all the evil of our time lies here.”

Who was Pier Paolo Pasolini and why does his work continue to challenge Italian power?

The figure of Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922-1975) cannot be reduced to a single discipline. He was a poet, novelist, filmmaker, linguist and, above all, the harshest critic of the anthropological changes that Italy suffered after the Second World War. Almost half a century after his murder on the beaches of Ostia, there is a credibility in his voice that makes him uncomfortable.

Originally from Bologna, Pasolini grew up in a home deeply marked by familial and cultural contrasts: a military father with fascist convictions and a mother, a teacher from Friuli, who instilled in him a love of rural language and lyrical sensitivity. This duality – the authoritarian versus the ancestral – shaped his youth.

From the 1940s he discovered a form of cultural resistance in the Friulian dialect. For him, language was not just communication, but a bastion against the homogenization of the modern world. However, his militancy in the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was prematurely cut short; In 1949 he was expelled from the party due to a complaint of “obscene acts”, which forced him to flee to Rome with his mother and thus began his most productive and painful period.

When he arrived in the capital, Pasolini settled not in the intellectual salons, but in the borgate: the outlying suburbs where those displaced by the Italian economic miracle survived. This experience gave rise to fundamental novels such as Ragazzi di vita (1955) and A violent life (1959). In it he portrayed young people who lived outside bourgeois morality, driven by primary instincts and a vitality that the author considered “sacred.”

His transition to film directing with Accattone (1961) and Mom Rome (1962) marked an aesthetic revolution. Pasolini used amateur actors and frames inspired by Renaissance painting to sacralize urban misery. For him, cinema was the crucial tool to capture the world before consumerism consumed it. His filmography developed from social realism to an examination of classical myths and religions:

►The Gospel of Matthew (1964): Considered by many to be the best cinematic version of the life of Christ, filmed with an almost documentary rigor.

►Trilogy of Life: Consisting of The Decameron, The Canterbury Stories And One Thousand and One Nightswhere he celebrated the human body and eroticism as forms of political freedom.

►Salò or the 120 days of Sodom (1975): His posthumous and most extreme work, a brutal allegory about how fascist power and modern capitalism consume and destroy the human body.

Nevertheless, Pasolini’s body was found brutally beaten and run over in the water harbor of Ostia in the early morning of November 2, 1975. Although a 17-year-old young man, Pino Pelosi, confessed to the crime, the inconsistencies in the evidence and the political climate of the “Years of Lead” in Italy suggest that it was an ambush orchestrated by those in power that the intellectual had systematically denounced.

Pasolini died as he lived: at the center of a contradiction he never wanted to resolve, defending a sacred past against a future he considered bleak. His legacy is not only artistic but also an ethical memory.

MV