“Forever, Robe. Always, always, always,” says the newspaper Today from Extremadura. “The rebellion and the talents of Extremadura are leaving”, headlines the front page The Extremadura newspaper. “It seems that the day presaged this very sad news,” said the mayor of Plasencia, Fernando Pizarro, of the PP, by telephone. People in Placentia took out their umbrellas this morning as they went about their routines. In the Plaza Mayor, three flags fly at half-mast. The loss of his most illustrious neighbor, Robe Iniesta, Bathrobeher Bathrobeleft this town of 45,000 inhabitants north of Cáceres perplexed.

Pizarro says he found out at dawn, thanks to a WhatsApp message from a collaborator of the singer. That everyone here knew that the leader of Extremoduro was ill. That he had retired to recuperate. They were impatiently awaiting his return to the stage. That his departure was very unexpected. That they placed a book of condolences in the Town Hall next to a painting of Robe’s disheveled face painted by Isabel, a person suffering from mental health problems who is part of an association which produced a Beaux-Arts work on the singer. And that Plasencia, said the mayor, had the privilege of being the place where Robe was born. “He left like the grown-ups, without making any noise. He was humble and discreet.”

No other news is talked about in the bars and stores of this town of 45,000 inhabitants. THE stories Instagram pages are full of songs from his prodigal son, the one who was born in this corner of Extremadura 63 years ago. To understand Robe’s impact on your city, ask any neighbor. Almost everyone has a close story with him. So much the better because they have already seen it on its cobbled streets. Because they know his family. Because they are friends of his sons, Cain and Naum. Because they have their files. Because they went to his concerts. Because they already saw him bathing in the Jerte River. And even jump from the bridge of the famous Playa El Benidor, an idyllic swimming pool a few kilometers from the city.

Or maybe it’s also enough to travel to 1989, a few months before the release of their first album, transgressive rock, when Robe himself asked his neighbors for 1,000 pesetas to finance it. Six years later, without knowing it, the inhabitants of Placentia experienced a unique and irreplaceable concert. It happened on October 14, 1995. “Covered with stars, the sky covered him,” says the chronicle of the concert in Northern Extremadura. Involuntarily, it was a farewell, an unexpected goodbye. Several generations of Placentia people grew up without seeing their local idol live for 13 years (1995-2008).

It was a story of disagreements with a PP mayor. “I will not facilitate the consumption of alcohol and other narcotics for young people,” said city councilor José Luis Díaz, announcing the ban on concerts by Extremoduro, Dover and other groups. “These types of performances involve noise and dirt before and after the performance.” EL PAÍS even headlined: “The mayor is afraid of rock”. Dover responded with “laughter and anger” to Díaz’s attitude. And they told him that they would send him a basket of fruit along with a case of non-alcoholic beer.

Robe, a sibylline, replied to him through a letter with verses from Miguel Hernández: “We must destroy you in your legations, in your stages, in your diplomacy. With hot machine guns and songs we will machine gun you, prehistoric woes.

Extremoduro, of course, continued to tour Spain, but now far from his hometown. The closest was Cáceres, about 80 kilometers from his home. How can we forget this July 6, 2002 when, a few hours after the concert, Robe spoke on local television. “Here I am,” he said, “I’m approaching the city. We’re violent and we like to fuck.” At the end, perhaps in case it hadn’t been clear before, he confessed: “I’m shitting on the mayor.” »

In 2004, the socialists regained power in Plasencia. “I like the city better now, of course,” Robe said. The Extremadura newspaper. And four years later he returned. It was an anthological and apotheotic concert. On the eve of the June fairs, May 31, 2008 was marked by a devilish storm. With suspension rumors everywhere. There was no opening act. The municipal football field was all mud and beer. The neighbors prayed to the Virgin of the Port, their patroness, to stop the flood as quickly and, if possible, immediately.

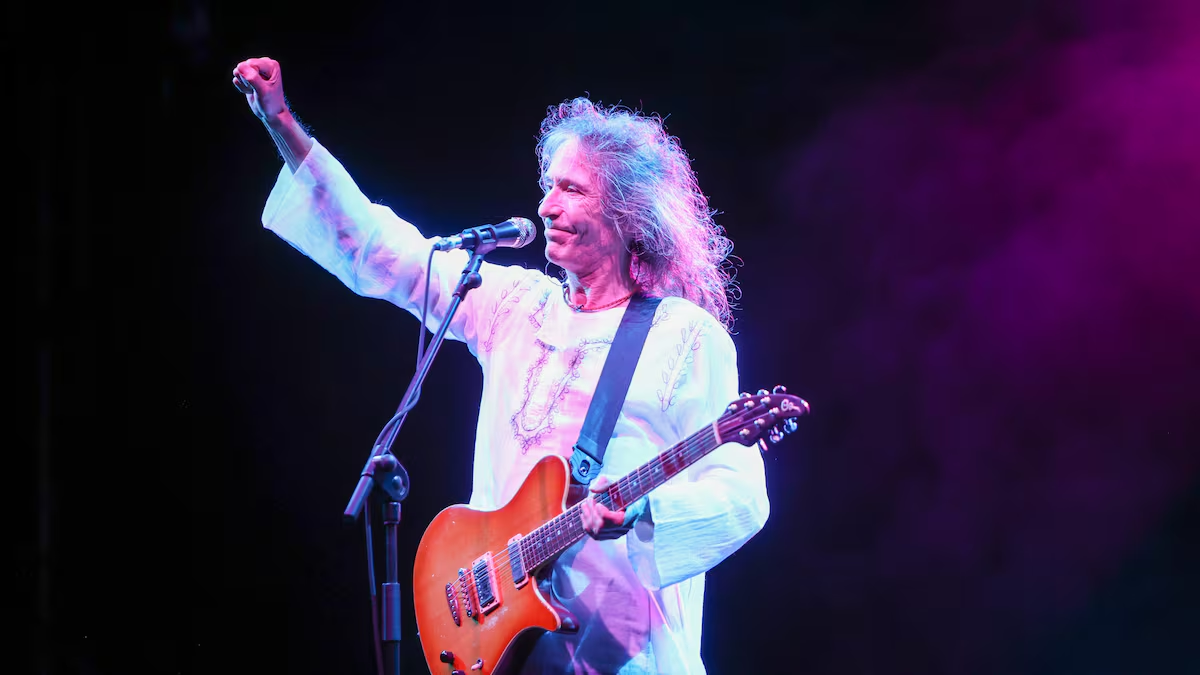

And the rain stopped. Above the stage, three fabrics hung from the ceiling. The one on the left fell first, between the chords of his Deltoya. The second fell: “The stove has gone out, nothing is working, where is the light? What is that in your eyes?” And finally, the center one fell. And there was Robe, again and in a skirt: “We are here.” Those who were in the first rows almost found themselves outside the room.

Seven years and six albums later, the Popular Conservatives took over the local city council with Fernando Pizarro, who promised a street in their name. “They told me they were going to give me one and I asked them for a palace,” Robe, 56, jokingly responded in another interview with Radio 3.

Already with the cold war finished, Robe included Plasencia in his solo tour with musicians from Extremadura and after another nine years of absence. The youth counselor who announced it was Luis Díaz, the son of José Luis Díaz, the counselor who banned him from playing for 13 years. And Robe handed over the 41,000 euros from the concert to the Town Hall coffers popular.

Now the news of his death has upset all plans for 2026, when the city would finally pay tribute to him as he deserves. Last November, all city councilors (including Vox) voted in favor of naming their favorite son.

Now, after Christmas, a rehearsal center for local bands that would bear his name would be inaugurated. A mural painted by one of the best local graffiti artists will also be hung. For next spring, finally, it was planned to give him a plaque with the name of his street, inaugurated last August: “Avenue Roberto Iniesta Ojea, Bathrobemusician, poet and soul of Extremoduro.” Under this sign, of course, reads a piece of one of his legendary words. For some here, perhaps the best: “I think it was from Plasencia”.