“I am not this fragile willow that trembles in the slightest breeze. I am an Afghan woman and it is right that I never stop lamenting.” These verses They belong to Nadia Anjuman, murdered Afghan poet in November 2005 following domestic violence. He was only 25 years old. Her death shocked the Afghan cultural world, but over time her name was relegated to the margins, as is the case with so many women whose voices are silenced twice: first in life and then in collective memory.

Nadia Anjuman She was one of many Afghan women who suffered violence in their homes.. For years, he expressed his pain, frustration and desire for freedom through poetry. I wrote because I could not speak freely. He wrote because the word was the only space that could not be taken away from him.

Under the first Taliban regime (1996-2001)Nadia was deprived of the right to formal education. Like millions of Afghan girls today, she had to drop out of school. However, he refused to abandon his studies. She follows clandestine classes organized by women, where poetry becomes a form of silent resistance. After the fall of the Taliban regime in 2001, he managed to complete his studies at the University of Herat and began to be recognized as one of the most promising poetic voices of his generation.

But talent did not protect his life. In 2005, she died as a result of her husband’s violence. Her story reflects a structural reality: even outside the direct control of the Taliban, many Afghan women remain trapped in systems that normalize violence and punish female autonomy.

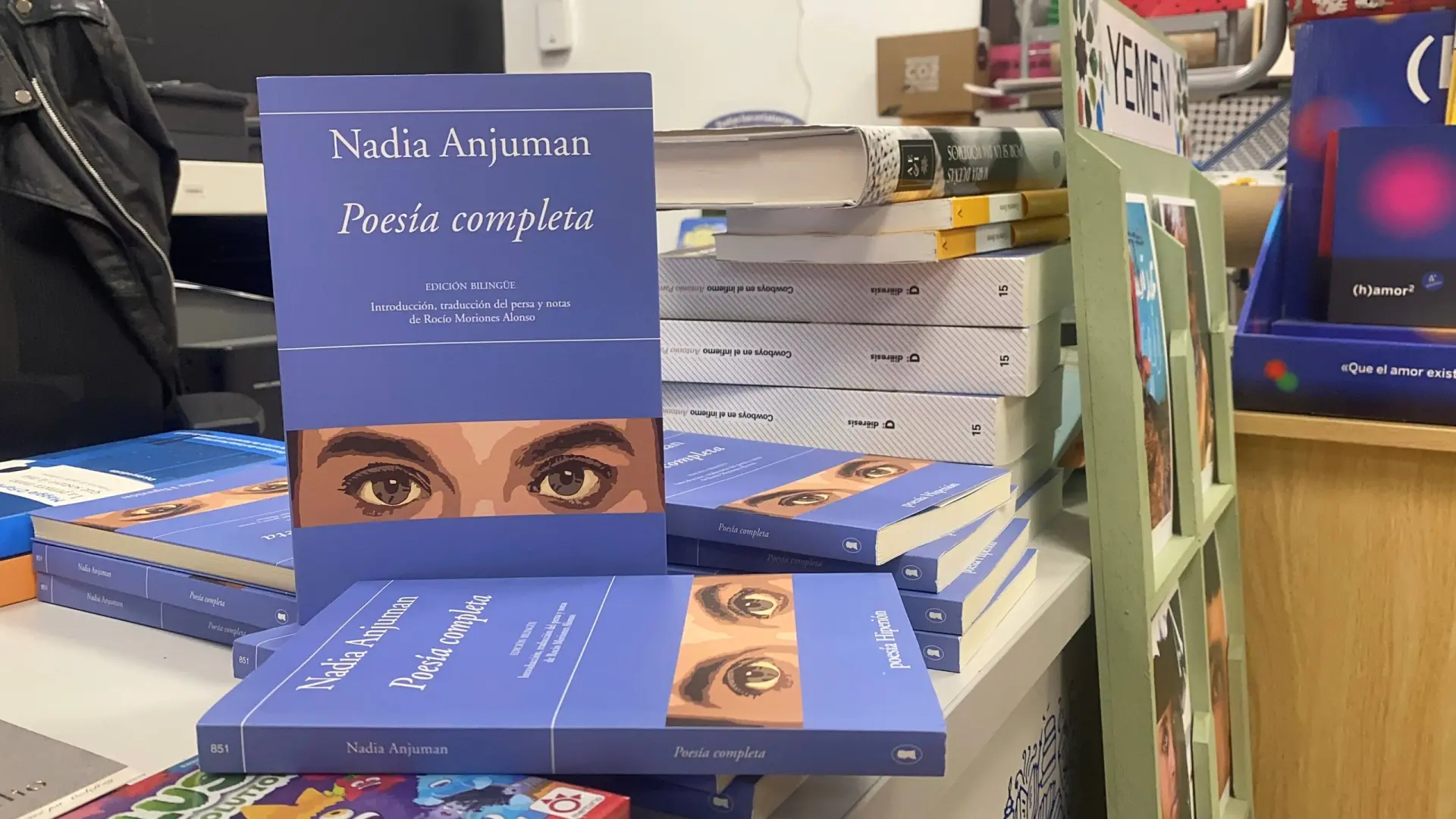

20 years later, far from Afghanistan, I met Rocío Morriones Alonso at the screening of the film Sima’s Song. This meeting was decisive. When she told me about her work translating Nadia Anjuman’s poems into Spanish, I understood that it was not just about literature. Translating these poems is saving a voice that we have tried to erase. and place it in a space where it can be heard without fear.

Today, Afghanistan lives again under the control of the Taliban. Since 2021, women have been systematically excluded from secondary and university education, work, public and cultural life. Books written by women were banned. Women’s literature has been removed from libraries, bookstores and educational programs. Writing, reading or publishing as a woman has once again become a risky act.

In this context, cultural projects developed outside Afghanistan acquire fundamental political and ethical relevance. The work of Rocío Morriones Alonso is not an isolated initiative, but a concrete response to the attempt to erase Afghan women from history. Translation of Nadia Anjuman’s poetry into Spanish breaks the isolation imposed by the Taliban regime and allows your experience to reach new readers.

I was invited to the book presentation at the Balqis bookstore in Madrid. The event was much more than a literary presentation. It was an exercise in collective memory and cultural solidarity. With Rocío, Parvin and Farjanda, at the request of the public, they read poems by Nadia Anjuman in Persian-Dari. For a few hours, a Madrid library was transformed into a space where the voice of an Afghan woman publicly exists again.

The meaning of the event went beyond poetry. At a time when the Taliban are trying to eliminate women from public spaces, listening to Nadia Anjuman in a European library reminded us that censorship is not absolute and that culture can cross borders even when people cannot.

This book is Nadia Anjuman’s first poetic work translated into Spanish. Its publication has obvious symbolic and political value: it shows that, even if attempts are made to silence Afghan women, their words continue to find a voice. Translating is not just about transferring words from one language to another; It’s transmitting a story, a wound and a resistance.

For Afghan women in exile, these types of initiatives represent more than simple cultural recognition. They are a form of emotional and political survival. We need the world to listen to us, not only as victims of an oppressive regime, but also as women who created thought, literature and memory even in the most adverse conditions.

Nadia Anjuman was murdered, but her poetry lives on. The Taliban are trying to erase Afghan women from the present and the future, but they cannot erase what has already been written. Every translated poem, every public reading, every published book is a crack in the wall of silence.

Nadia Anjuman’s story reminds us that poetry can be a form of resistance and that listening is also a political act. In a time of censorship and exclusion, giving space to these voices is not a symbolic gesture, but a collective responsibility.

Afghan women are not weak willows. We are still standing. We continue talking.