At the beginning of December 2024, the name of a Brazilian scientist appeared in 13th place in a ranking: that of researchers with the most retracted, or “unpublished,” articles, a list established by the Retraction Watch Database site. And, this year, he stayed there.

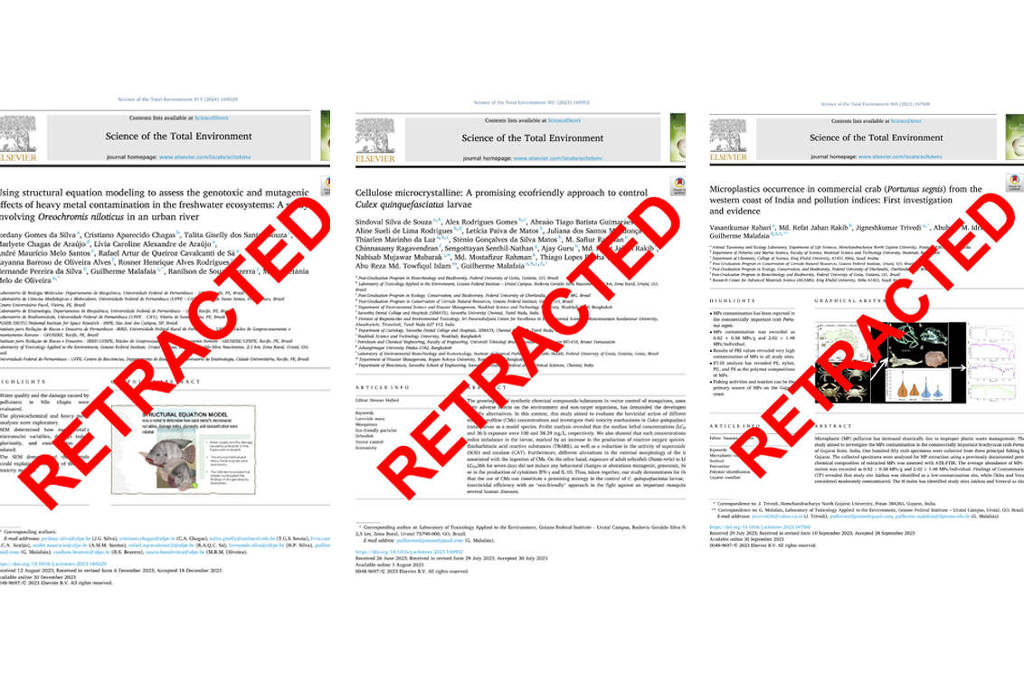

Biologist Guilherme Malafaia, from the Federal Institute Goiano (Goiás), had 46 scientific articles withdrawn last year, all from the scientific journal Stoten (Total Environmental Science), published by Elsevier.

The reason for the retractions, available on the Retraction Watch portal, was the alleged insertion of false information in the reviewers’ recommendations for their manuscripts. Malafaia denied the accusation and said he did not have the opportunity to fully defend himself during the process.

The case has attracted attention because of the high number of retracted papers attributed to a single researcher and, experts say, is sparking debate about bad scientific practices and the incentives that favor them.

Although cases of scientists with dozens of retracted papers are rare, the accelerated growth of global scientific production has also led to an increase in the number of retractions, according to Fábio Kon, professor of computer science at USP’s IME (Institute of Mathematics and Statistics).

“It is important to emphasize that these cases are rare and that we publish hundreds of thousands of articles every year and only a few hundred end up being retracted due to serious problems. That said, it is something worrying and it needs to be curbed,” he said.

Kon, who coordinates a free USP course on good scientific practices available on the Coursera platform, associates the increase in retractions with the academic logic that values publication in large volumes. “As the scale of science and the number of articles published increase, we need to strengthen oversight mechanisms to ensure research integrity.”

According to him, the way in which researchers are evaluated, particularly in the granting processes and public competitions, contributes to this scenario. “Unfortunately, I see many universities that, in the competition rules themselves, say that such a ‘paper’ is worth that many points, which is not recommended today by the best practice guidelines for publishing and research.”

“Over the past decade, we have seen some of these (predatory) publishers grow significantly, and today they publish hundreds of thousands of articles every year, making billions in profits at the expense of science and society,” Kon adds.

According to the professor, the emphasis on quantity, not quality, creates a permissive environment for scientific misconduct. “If there is an incentive to increase the number of publications at all costs at the expense of research quality, we will be faced with those who would rather have five poorly done ‘papers’ published in dubious journals than have one or two good ones in a top-ranked journal.”

He also said that the problem of scientific integrity is linked to dishonesty. “Most people are honest, but in every human endeavor there are dishonest people.”

To cope with the growing volume of manuscripts, some authors are turning to so-called “paper mill journals”, which favor quantity over quality. These publications often promise a review and editorial decision within a few weeks, which should be taken as a warning sign, Kon said. “No serious scientist can formulate a correct and profound opinion in a week. And I have seen some opinions in these magazines.”

Academic productivity data reflects this expansion. The latest survey by Elsevier and the Bori agency, published this month, shows that almost 3 million articles were published worldwide last year alone.

Although more modest compared to this observed volume, the number of retractions has also increased, from 1,542 in 2015 to 5,881 in 2024, according to the most recent data available on the Retraction Watch platform.

Ivan Oransky, co-founder of Retraction Watch and executive director of the Center for Scientific Integrity, said that about 1 in 500 papers are retracted each year worldwide, which equates to 0.2%. “We think this percentage should be higher, around 2%, or even more. Unfortunately, fraud and scientific misconduct are more common than we think.” This was the case until 2024.

The problem, for the journalist, goes beyond fake reviews and includes the growth of “paper mills,” which offer complete packages for expedited publication. “And it all has to do with the pressure of ‘publish or perish’.”

Created in 2010 by Oranksy and Adam Marcus, now editor-in-chief of Medscape, Retraction Watch came about after Marcus exposed one of the biggest scientific misconduct scandals of the century, involving Dr. Scott Reuben, who defrauded dozens of studies and was sentenced to prison to obtain funds for nonexistent research. “We quickly realized that it was not possible to track all retractions and that the available databases were incomplete,” Oransky said.

Thanks to philanthropic funding obtained as early as 2015 (previously the work was voluntary), the Retraction Watch Database (RWD) was publicly launched in 2018 and has become the leading global reference for quantitative analyzes of scientific retractions. “Since then, publishers have become more transparent in their retraction notices.”

Incorporated in 2023 into Crossref, a nonprofit organization that manages digital article identifiers (the DOI indicators of scientific articles), the database is now free and allows any interested party to analyze patterns, trends, and systemic failures in the publishing system.

Despite this, Oransky believes that scientific publishers tend to position themselves as victims of the problem, even though they are also part of it. “Productivity metrics and academic rankings have created a market addicted to the H-index and citation counts. When viewed in the light of day, the problem is obvious, but publishers avoid recognizing their role in the system of productivity.”