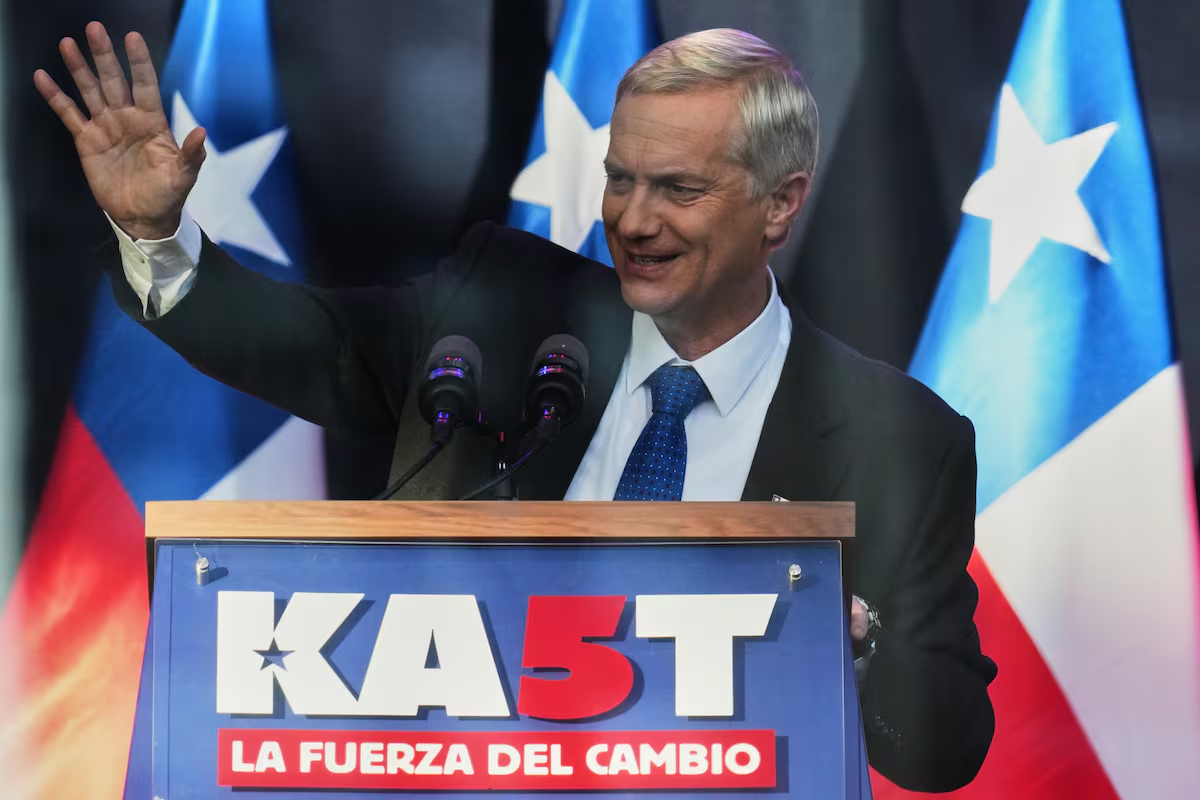

A possible presidential victory for José Antonio Kast this Sunday would not be an accident, but a symptom: the clearest expression of the exhaustion of a political cycle and the failure of traditional forces – left, center and right – to offer credible responses to a country crossed in recent years by a superposition of crises of order, governability and expectations. Kast does not appear out of nowhere: his candidacy capitalizes on accumulated fears and lingering unease that conventional politics has been unable to address.

In this context, a possible large victory should not be interpreted as majority adherence to a coherent ideological project, aligned with radical conservatism and market liberalism, but as the result of a negative convergence. On the one hand, a structural malaise which seeks immediate solutions; on the other, an electoral offer which, by placing the Communist Party at the center of the competition, pushes large sectors of the electorate to vote more out of rejection than out of conviction. Added to this is a vote of punishment against a Government whose transformation project was rejected at the polls, particularly after the failure of the 2022 constitutional process.

Even if the result cannot be considered fortuitous, it would be hasty to read it as the crystallization of a new stable political divide between restoration and refoundation. Since 2010, Chilean politics has entered a sequence of increasingly rapid alternations, evoking a pendulum movement without a point of balance. After two decades of Consultation Governments, the return of the right with Sebastián Piñera opened a cycle marked by successive turning points: the return of Michelle Bachelet in 2014 with a more left-wing speech; Piñera’s second term in 2018, abruptly interrupted by the social epidemic of 2019; and a constituent process which, despite broad citizen support at the start, ended up being rejected twice, in 2022 and 2023.

At the same time, the country went from enthusiasm for a new disruptive left, which came to power in 2021, to the strengthening of a hard right during the constitutional process that followed, to then lean again towards more moderate options during the subnational elections of 2024. This shift responds less to underlying ideological transformations than to strong political and emotional volatility, fueled by weak partisan ties and by a population particularly sensitive to the situation. It is therefore premature to interpret this conservative rebound as a structural turning point. of the Chilean electorate.

Nor does it seem appropriate to place this result in the terms of a nostalgic justification of Pinochetism. Chilean society continues to be largely critical of Augusto Pinochet’s authoritarian legacy, although surveys reveal a persistent trend: About a third of the population now has a positive assessment of the former dictator or views the 1973 coup as justifiable. This favorable perception is largely based on a selective reading of its economic legacy. For part of these sectors, the dictatorship would have laid the foundations for the modernization of the country, promoted growth and “liberated” Chile from Marxism. But more than an explicit endorsement of authoritarianism, these data seem to express dissatisfaction with the present: economic stagnation, insecurity and a feeling of generalized disorder.

It is in this context that José Antonio Kast appears less as the heir of nostalgia than as the spokesperson for a reaction. His proposal does not seek to reopen the past or redefine the development model, but rather to restore an order that, according to its history, would have been eroded by progressivism, permissiveness and cultural fragmentation. The paradox – or, if you like, the irony – is that this promise of restoration of public order, state authority and a traditional conception of the nation refers to a profoundly Chilean ideological tradition, the unionist doctrine of subsidiarity, which was one of the doctrinal pillars of the Pinochet regime and which was projected to the right through the UDI, a party from which the Republican Party would later separate.

In the economic field, Kast promotes a program focused on lowering taxes, contain public spending apply efficiency criteria in social policies and promote private investment. The stated objective is to regain market confidence and reactivate growth, based on the principle that this will ultimately benefit society as a whole. However, the caution with which those around him consider possible adjustments reveals the limits of this approach. “If we say what we are going to reduce, the next day we will have the street on fire,” Rodolfo Carter, one of its spokespersons, recently admitted. This diagnosis also coexists with a reality marked by job insecurity, household debt and persistent inequalities, which raises questions about the social viability of an agenda focused almost exclusively on macroeconomic stability.

The reactivation of this conservative tradition is projected with particular force in the field of security, probably one of the axes of a possible Kast government. Criminal reinforcement, unrestricted political support for police forces and extensive use of exceptional tools are part of a repertoire aimed at delivering rapid results. In the candidate’s speech, insecurity, irregular migration, organized crime or social protest do not appear as complex phenomena requiring global responses, but as symptoms of a loss of state authority and excessive tolerance towards the democratic system. The call for a “strong hand” thus joins the unionist logic: first order, then deliberation; first authority, then politics, a sequence that favors immediate effectiveness over slower periods of democratic debate.

Added to this is the challenge of governance. Without clear majorities in Congress, many of these proposals would depend on cross-cutting agreements, which would place him in a dilemma: opt for pragmatism and moderation, with the consequence of eroding his strongest base, or govern from confrontation, further straining the political system.

In short, Kast’s coming to power would not resolve Chile’s contradictions, but it would make them more visible. It would reorder the priorities of public debate and force the country to confront uncomfortable questions about security, inequality, rights and historical memory. In this sense, a possible victory would not mark the end of the Chilean crisis, but rather the opening of a new stage in a still unfinished process: the search for a lasting balance between order and democracy, authority and pluralism, stability and change.