Sergio Fajardo (Medellín, 69 years old) faces this presidential campaign, the third in a row, with a clear line: to show that he has learned from the past, by projecting a style of leadership closer to that sought by the majority of Colombians. “I didn’t speak like that,” he says of seeking a more direct tone in his interventions. And he explains that his strategy, the first that he does not build with his own intuition, but with an expert – the Spaniard Antoni Gutiérrez Rubí – seeks to escape from the political position that usually accompanies it. “I am not talking about the center, which is not a sufficient political form to access the second round, and I have never classified myself as being from the center. I come from a civic, citizen movement, outside of this political geometry. This is why I am talking about building a new majority,” he explains.

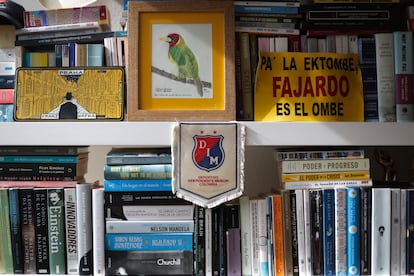

He hosts EL PAÍS in his bright apartment in the northeast of Bogotá, where books, photographs and drawings of his children and grandchildren, and memories of Deportivo Independiente Medellín mix. The change is not complete: account that you were recommended to use blazer for the photographs that accompany the interviews, but he refuses to stop going out in jeans and a collared shirt, an image that has characterized him since he went from being a university mathematics professor to a candidate for mayor of Colombia’s second largest city.

The candidate who in 2018 had accumulated 4.6 million votes and was very close to reaching a second round that all the polls indicated he would win, fell four years later to 865,000 supports and a very distant fourth place. It is a painful memory that, he says, sitting at a wooden table of eight people, enjoying the afternoon light of Bogotá, led him to face this new campaign with a different perspective, to try new things.

He says he is happy to lead the campaign in a different way and pauses the interview to proudly show a recent video posted on his social networks. At a rally, microphone in hand, he answers a question: “If I have balls (of balls) or if I have no balls, I will answer here to the man who worries about my balls”, he begins, then he affirms that character is not to shout or to mistreat, and that many corrupt people can be courageous in this sense, but their proposal is another: to do things in a different way.

— It was unexpected, I never use an expression of that nature. This happened in Galapa, in the Atlantic, because the people on the coast speak differently. Here they would have told me: “You are lukewarm and you don’t have the strength to protect yourself. » This would have gone unnoticed, because in all the interviews they tell me, they remind me that I went to see whales. Not there. He said to me, “No, shit, do you have balls or don’t you have balls?” I responded naturally, we release the video and it becomes a hit. How is life…why should I think about this stuff.

It’s an example of his learning, of this new Fajardo, he emphasizes with enthusiasm. According to him, this novelty contributes to his strategy of showing that the voter’s decision is between the extremes – “both”, he emphasizes – and him, who claims to be the one who seeks to take a step “forward”, not towards an intermediary between them, but far away, leaving them behind. This time, he leaves aside the board or notebook on which he had made mental diagrams during previous campaigns that he showed to his interlocutors, a legacy of his years as a teacher, he remembers aloud the central results of the recent Invamer survey as a starting point for his strategy.

—At one extreme, Iván Cepeda appears to be an obvious candidate and leader. In the other, De la Espriella is strong, although less than those around him thought after so many paraphernalia like his launch at the Movistar Arena. I come behind. But this same poll shows that in the second round Cepeda crushed Abelardo, that I beat De la Espriella and that against the senator we were in a technical tie. Today I am the only one who can beat Cepeda

—And what would happen if the candidates at these two extremes were not Cepeda and De la Espriella, but more moderate figures?

-If one of them falls, Fajardo gets back up. Better. But President Petro is going to spark the polarization that exists in Colombia, and it’s not because of a few individuals, but because of what they represent, the extremes.

Last week, the former mayor of Medellín and former governor of Antioquia also spoke about the road ahead to reach the first round. Last Monday, when the deadline for candidates to announce their intention to participate in a consultation between them expired, he closed that door. In a public statement, he explained his objections to this mechanism, a decision that changed the course of the presidential elections. Instead, he proposed the possibility of agreeing with other candidates on a structured survey, which does not ask about voting intention, but rather about the desirable characteristics of a candidate, in order to select the one who best matches this ideal. It’s a sketch of an idea, he explains.

— You have decided not to participate in any interparty consultations, unlike in 2018 and 2022. Why?

— Because after the vote, the results of the consultations are compared with each other, and those who have candidates with machines, who mark lists for Congress with politicians of this type, obtain many more votes. This has already happened, and this time, on the right, Álvaro Uribe is on the Senate list, and on the left, the entire Historical Pact. My life project is not to be leader of the center or to win a consultation of the center, it is to be president of Colombia.

— Is this a lesson from what happened after you won the 2022 referendum and several of your allies ended up supporting other candidates?

— We must break the axiom according to which consultations bring people together. But I decided not to talk about what happened, but rather to learn, like other lessons in life.

What he’s talking about, and quite a bit, is the current president. He describes Petro’s tenure as “chaotic.” He emphasizes that he does not know how to plan, maintain a management system or follow a strategy. “Who is responsible today for total peace, who can we ask? Have the 25,000 troops that Petro ordered them arrived in Catatumbo?” he questions, then describes as a “shame” the episode in which the Minister of Justice at the time, Eduardo Montealegre, described his Interior colleague, Armando Benedetti, as corrupt, only to then make peace thanks to the mediation of the current pre-candidate Roy Barreras. “That’s why people don’t trust politicians: one day they insult each other and the next day they kiss each other. No coffee cures corruption.”

But more than the fight against corruption, Fajardo’s old banner, in this interview he focuses on security. He says this is the concern he has felt most among the Colombians he has visited during these months, during which he has visited 29 of the country’s 32 departments,

— Would you use the tool of bomb attacks, like those that Petro has resumed despite the risk of death of minors recruited by illegal armed groups?

—If I had been president, we would not be here,

— In what sense?

— That if I am president, I lead in a different way. On August 7, the Petro trading pattern ends, but I can’t say more because we don’t know what they will deliver to us, there is still a lot of time and a lot of things will happen.

Fajardo lists his projects, the security plan, the anti-corruption plan, the health plan that he has already delivered. He emphasizes that those who come will be presented in a “different” way and that he is happy to learn how to use the networks to do this. He separates from the pile of papers that fills one end of his table the current projects on these issues, and others of his proposals for 2018 and 2022. Let us remember that he has supported all the peace processes in the country. “But we must learn lessons,” he repeats like a mantra.

Asked about inequalities, he takes another newspaper, the press release in which he announces not going to the consultation, to read it directly: he says that the country needs “a policy that understands, recognizes and knows how to move forward in the solution of the deep inequalities between people and regions of our country, which has the capacity to guarantee the security they demand today”.

And Fajardo is ensuring that criticism of Petro aligns him with the right. He shows a list of dozens of people he spoke with throughout the year, one-on-one, about the country. He points out that on one side of the red sofa in his living room sat the pre-candidate Juan Carlos Pinzón and on the other the assassinated Uribe senator Miguel Uribe Turbay, that at the head of the table was Iván Cepeda and in a chair next to him, the Petrist senator María José Pizarro. He was with Uribe Vélez, with Cardinal Luis José Rueda, with But, he clarifies, he would never sit like this with De la Espriella.

-Why not?

—With a guy who is capable of saying that he is coming to empty the left, I will never be anywhere in the world in my life.

— Worse then, why talk to everyone?

— Because I am going to be president of Colombia and I must understand the protagonists of our country, speak with them with respect. I’m ready to do it.

The sun sets, the coffee Fajardo prepared runs out, and he highlights the accomplishments he had when he was mayor and governor, the way he administered, the deals he made with politicians of all stripes without resorting to bureaucratic quotas. He smiles when talking about the volunteer teams supporting him across the country: “People are very enthusiastic. After the disaster of 2022, it couldn’t be worse. I’m resilient and what I’ve learned since then, in terms of emotional intelligence, is a lot, and I’m happy about that,” he concludes with a smile.