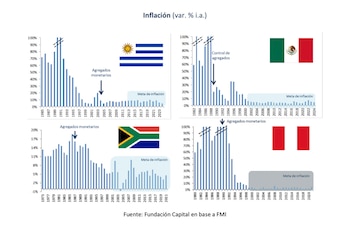

Several countries adopted monetary and exchange rate policies to curb inflation and stabilize their economies. The analysis of these cases, for example in Peru, South Africa, Mexico and Uruguay, provides concrete indications of the instruments and phases that could be considered in a context where the consumer price index (CPI) still does not break through the 2% mark.

With this in mind, Fundación Capital analyzed various stabilization experiences and currency regimes used for comparison. At an event convened by Fundación Mediterránea, Julio Velarde, president of the Central Bank of Peru (BCRP) for 19 years, shared his experiences at the helm of the institution and the “lessons” to be taken into account.

In 1990, when inflation in Peru exceeded 7,000% per year, the government adopted a system of monetary control – particularly the private money supply M1 – as a key tool for containing price increases. At the same time, a regulated system of floating exchange rates was introduced and emphasis was placed on achieving fiscal balance and ending the dominance of public spending over monetary policy.

The transition was completed with a series of institutional reforms aimed at strengthening the independence of the central bank. The 1993 Constitution enshrined this orientation: it defined monetary stability as the main task of the BCRP, guaranteed the free ownership of foreign currencies and expressly prohibited the granting of financial resources to the state treasury.

In 1994, when inflation had already fallen to around 24% per year, Peru began transitioning to an inflation targeting system. This program was completed in 2002, when the price index stabilized at around 3% per year. Since then, the Andean country has recorded single-digit inflation for 29 consecutive years, with a current target of 2% annually, with a margin of +-1%.

Also worth mentioning are the cases of South Africa (1986), Mexico (1987) and Uruguay (2002), where the monetary control regimes functioned as a transitional phase. After inflation fell, these countries moved to targeting programs.

For example, the Central Bank of South Africa began setting explicit growth targets for the M3 aggregate – which includes cash, demand deposits and time deposits – in 1986 and only formally introduced an inflation targeting system in 2002, when inflation was around 5.7%.

In the case of Uruguay, the monetary base was used as the reference aggregate for the first time (explicitly since 2003), changing in 2006 to M1, which includes money in circulation plus demand deposits. The classic scheme of Inflation target It started in 2013 with an inflation rate of almost 8%.

The Mexican case has some differences. Although it did not use a money supply targeting system, it resorted to a contractionary monetary policy and switched to an inflation targeting system in the early 2000s – with inflation approaching 9.5%. A common point across the three countries was fiscal consolidation, which is key to anchoring expectations while improving sovereign risk and access to finance in international markets.

Stock market strategies also showed nuances. Mexico initially maintained the exchange rate as a nominal anchor Crawling peg and then with replacement bands. Uruguay, on the other hand, moved towards a managed floating regime, a similar path to South Africa, which already had to intervene frequently due to low international reserves.

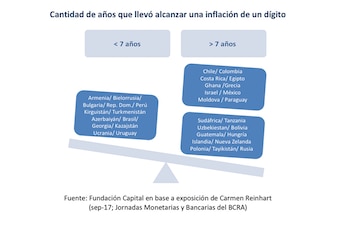

“International experience shows that the inflation targeting regime is usually introduced at average inflation rates in the order of 6-9% per year.” In emerging countries, according to the Argentine economist Guillermo Calvo notes that “interest rate adjustment (IRT) is inherently a weak nominal anchor” in undeveloped economies. In fact, he argues that financial shocks destabilize any interest rate-based regime and central banks need currency interventions and reserves to prevent this Inflation target “Pure” is not applicable in this type of countries (due to their structural fragility, high dollarization and capital outflows),” they opined from Fundación Capital.

In the last one Personnel report Regarding the agreement between Argentina and the IMF, the organization notes that “the use of money as a nominal anchor offers a combination of monetary policy autonomy and operational simplicity, making it a suitable option for central banks seeking to build credibility.”

He also adds: “As targeting monetary policy regimes succeed in reducing high inflation, they tend to gradually evolve towards a greater emphasis on inflation itself, rather than focusing solely on monetary growth objectives.”

In this sense, the BCRA had already analyzed money demand in 2006 using time series from 1975 to 2005 and found a positive long-term relationship between the M2 aggregate (circulation plus deposits in savings accounts and current accounts) and inflation.

“Monetary policy in our country could be clarified and made clear with a transition plan with transactional private money supply M2 as a quantitative target, together with a monetary program with forecasts for dollar purchases and broader monetary aggregates, a topic that we also cover in the next section,” concluded Fundación Capital.