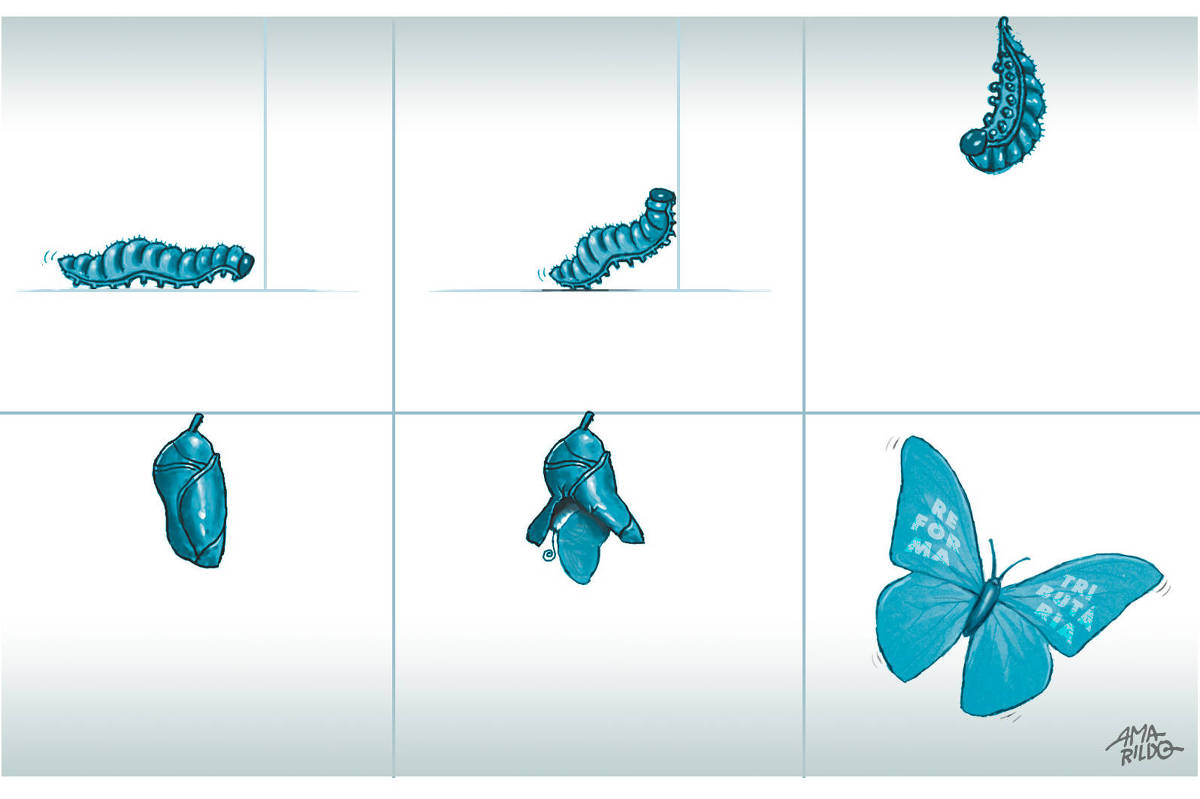

The tax reform on goods and services is not just a rearrangement of the system: it represents an internal transformation of Brazilian companies, a structural change that will affect finances, operations, technology, people and governance.

The tax reform debate is usually presented in technical terms, such as rate changes, impacts on productivity and the business environment, new taxes and simplification.

It will certainly be a tax reform, the most important in the last 50 years in Brazil. But above all it will be a reform of the functioning of businesses. And how we understand the difference different leadership styles can make to the future of their organizations.

From 2026, Brazil will begin the transition to a VAT (value added tax) with broad financial credit, destination taxation with uniform tax bases and more standardized rules. However, simplification does not eliminate implementation complexity. On the contrary: it shifts the challenge within organizations. And this is why the next few years will be decisive.

The first impact is technological. Internal systems will need to be reprogrammed, counting engines rebuilt, records adjusted, controls automated. The new model requires precision: the credit is automatic, the invoice becomes smarter and the tax can be collected via the split payment mechanism, in which the tax part of the payment goes directly to the government. This reduces payment defaults and compliance lapses, but increases reliance on reliable systems.

In the past, tax risk came from interpretation. From now on, it is born from an operational, or even technological, failure.

Another profound impact concerns financial logic. The reform changes relative prices, redistributes competitiveness between sectors and modifies margins that previously seemed stable. With better alignment of taxation between goods and services, industrial companies tend to regain their efficiency; Service sectors tend to face tax pressure. Pricing will need to be reviewed line by line and performance indicators such as EBITDA (operating margin) and ROIC (return on invested capital) will need to be recalibrated.

In addition, the treasury will be rethought. Split payment removes some of the flexibility that existed in the previous model on business cash flow. There will be more credits accumulated at the start of the transition and more working capital planning needs. The financial industry is already beginning to anticipate this shift, which could accelerate mergers and acquisitions to address this legacy.

At the operational level, the reform must reorganize supply chains and the logistics structure. Without predatory tax wars, location decisions cease to be fiscal and become economic again. Industrial facilities, distribution centers and supplier partnerships will need to be reassessed. Reorganization may generate short-term costs, but tends to increase structural efficiency. States and municipalities will be able to reshape their incentives which, if they continue to make sense, will have to pass through public budgets in the form of subsidies, financed by the new regional development funds.

All this requires new skills. Tax professionals must be quickly prepared to understand data, technology, automation and operations. The tax domain ceases to be an interpretive protocol and becomes a technical-operational system, integrated with information technology (IT), finance and operations.

The central question is therefore not “what does the reform change?” “. And yes: “Are we aware of the challenges and ready to exploit the new model?”

And here is the role of internal governance and boards of directors.

Tax reform is a governance issue; not because boards need to master the technical details, but because the scale of change requires strategic coordination, risk monitoring, management prioritization and extreme attention to stakeholders. And all this in a cycle characterized by extremely high investment costs and immense challenges in its allocation.

It is the Councils which must guide the company in revising its price and margin structure; be technologically ready by 2026; assess the financial risks of the transition; reexamine contracts and supply chain dependencies; prepare your teams to operate with new systems and rules. And finally, redefine your medium-term value generation strategy in the face of new relative prices and the various compliance and supplier relationship issues.

A transition of this magnitude cannot be delegated. It requires vision, alignment and the ability to execute. There are three which directly depend on the quality of governance.

Ultimately, tax reform will be a huge test for Brazilian businesses. Some will emerge stronger: with more efficient operations, more robust controls, a clearer cost structure and less legal fragility (less litigation). Others, less prepared, could face margin losses, operational disruptions, cash flow difficulties and reputational risks.

The difference between one path and another will lie less in the reform itself than in the capacity for internal organization, as well as in the objectivity of the actions of executives and councils.

Tax reform will change businesses. And it will be businesses, as a whole, that can change Brazil and move it out of the ranking of the most complex, contentious and inefficient tax systems on the planet.

The transition will be very complex for businesses. But if we succeed in this endeavor, in a few years our companies will be more efficient and more competitive; your clients or consumers will have a more transparent vision of the tax burden they pay; investors will have a more positive view of the business environment; and the country will potentially experience greater, more sustained growth.

PRESENT LINK: Did you like this text? Subscribers can access seven free accesses from any link per day. Just click on the blue F below.