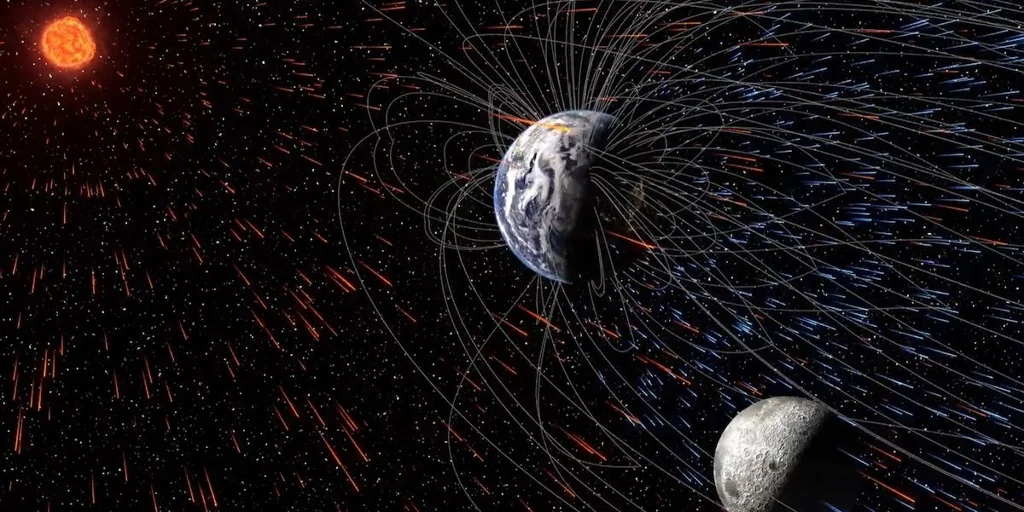

In what could be described as an extraordinary display of interplanetary generosity, Earth has shared its air with the Moon for billions of years. And this, moreover, thanks to the same tool with which it protects us from solar radiation: the … magnetic field.

The discovery, recently published in “Nature Communications Earth & Environment”, has just been announced by a team of astrophysicists from the University of Rochester. Until now, it was thought that Earth’s magnetic shield acted as a barrier preventing our atmosphere from escaping into space, but the data says otherwise: This shield also functions as a funnel, an invisible “highway” that transports Earth’s particles directly to the lunar surface.

Since the Apollo astronauts brought home several kilos of lunar rocks and dust (the famous regolith), scientists have wondered how it is possible that these samples contain such a quantity of volatile elements, notably nitrogen and rare gases, which simply should not be there.

The reason is that, technically, the Moon does not have an atmosphere like ours but an exosphere, an extremely tenuous layer of gas that, for the most part (about 70%, according to a recent MIT study), is due to “impact vaporization.” That is to say micrometeorites which strike the lunar soil and raise dust and gases. The remaining 30% has always been attributed to the solar wind, the jet of charged particles that continually emanates from our star.

Scientists thought the magnetic field was preventing the atmosphere from escaping, but new simulations show it acts like a funnel connecting the two worlds.

But the accounts didn’t really add up. The solar wind and meteorites, in fact, could not alone explain the isotopic composition of the nitrogen found in the samples reported by Apollo. It had to come from somewhere else. And that place, some began to suspect, might be Earth, although no one imagined by what mechanism.

Different hypotheses have been put forward. A 2005 study from the University of Tokyo suggested, for example, that this transfer of the Earth’s atmosphere to the Moon would only have been possible at the dawn of the solar system, when the Earth did not yet have a powerful magnetic field. The logic, in fact, was that once the magnetic shield was “turned on”, the leak of atmosphere would have stopped.

From shield to cannon

And that’s where the team from the University of Rochester, led by geophysicist John Tarduno, comes in. To find out the truth, the researchers ran simulations of two different scenarios: a “primitive Earth” without a magnetic field and buffeted by a fierce solar wind; and a “modern Earth,” with its powerful magnetic shield in place and a much gentler solar wind.

“The simulation of the modern Earth – write the researchers – matches the data much better. And the reason was completely surprising: the magnetic field did not block the particles’ exit, but rather channeled them.

The mechanism is violent and elegant at the same time. The solar wind hits our atmosphere and removes charged particles (ions). But instead of being lost in the void, these particles find themselves trapped in the lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. To which is added that our magnetosphere is not a perfect sphere; The pressure of the solar wind distorts and stretches it along the night side of the Earth, giving it the appearance of a gigantic comet’s tail.

The discovery explains why the Apollo samples contained so much nitrogen and suggests that lunar regolith is an intact library of Earth’s chemical evolution.

And it is there, in this “queue”, known as “magnetocola”, that the magic happens. When the Moon, in its 28-day orbit, passes behind the Earth (during the full Moon phase), it crosses this magnetic tail. So, about five days a month, our satellite receives a direct shower of Earth ions (nitrogen, oxygen and other volatiles) which travel along this magnetic “highway” until they crash and become trapped in the lunar soil.

The Moon is rusting, and it’s our fault

The new study fits perfectly with other pieces of the “puzzle” that have emerged in recent years. In 2020, for example, researcher Shuai Li, from the University of Hawaii, stunned the scientific community by announcing that he had found hematite on the Moon. It is essentially iron oxide. But for iron to rust, it requires oxygen and water, two elements that are lacking on the Moon. Li then proposed that the oxygen needed to “oxidize” the Moon came from Earth’s upper atmosphere, navigating through the magnetic tail, as the Rochester model now confirms.

The magnetic tail also acts as a “temporary” (five days a month) protective shield for the Moon, blocking the solar wind (which is rich in hydrogen and makes oxidation difficult) and allowing Earth’s oxygen to do its work. That is to say, we literally “rust” our neighbor every time there is a full Moon.

A time capsule

The implications of this discovery are fascinating. Because if it turns out that this process has been going on for billions of years, then the lunar soil is not just inert dust. It is a faithful fossil record of the Earth’s atmosphere.

The atmosphere of our planet has changed radically over geological eras. There was a time without oxygen, then came the Great Oxidation, then changes in nitrogen levels… Each of these stages would have sent a different chemical mixture to the Moon, and all of this would have been recorded in the layers of lunar regolith.

We’re not just sending it nitrogen: previous studies confirm that terrestrial oxygen travels to the Moon and slowly oxidizes its surface

In other words, as the authors of the study suggest, the Moon thus becomes a “time capsule”. And if we manage to drill its surface and analyze the deep layers of lunar soil during future Artemis missions, we could then read the chemical history of the Earth in a completely new way, impossible to do “down here”, where erosion and plate tectonics have erased the traces forever.

There were already plenty of reasons to return to the Moon. And from now on we have another one.