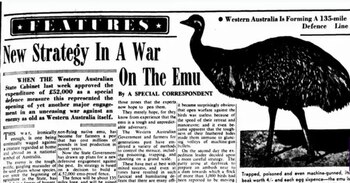

He December 10, 1932After a month of failed military operations, the Australian government admitted defeat: it withdrew from the battlefield and publicly assumed it had failed. This was neither an international conflict nor an internal rebellion. Australia had just lost a war against thousands of emusthe huge, flightless birds that steadfastly crossed the wheat fields in the west of the country.

The unpublished “Emu War” It was the result of an explosive combination: farmers ruined by the Great Depression, crops destroyed, urgent political decisions and wildlife whose behavior was ultimately more effective than any military strategy.

This December, while the world’s newspapers were reporting on political unrest, the rise of Nazism or tensions in Asia, Australia was experiencing its own absurd tragedy. He had fired thousands of bullets, mobilized troops and made official statements. But emus – hard, fast and unpredictable – They were still there, alive and apparently immune to the state apparatus.

To understand why a country decided to use weapons and declare war on the birds, we must remember rural Australia in the early 1930s.. The global economic crisis hit mercilessly and the agricultural economy was in ruins. Exports had collapsed, the price of wheat had fallen to critical levels, and thousands of World War I veterans – who had been resettled as farmers by the government itself – were surviving in debt and virtually abandoned.

The situation was particularly serious in the Campion region of Western Australia. Many of these former soldiers had been given cheap land as part of an ambitious plan to promote agriculture and reintegrate fighters into the workforce. But the program was poorly designed: The climate was harsh, the infrastructure inadequate and the land difficult to work. In 1932, many of these manufacturers were on the verge of bankruptcy The emus have arrived.

Every year, after breeding season, these giant birds migrated inland in search of water and food. This year they found a feast: fields of wheat replanted by farmers desperate to save what was left of their crops. It is estimated that within a few days about 20,000 emus raided Campion, destroyed fences – which also allowed wild rabbits entry – and then went on a rampage, eating entire crops.

The producers tried to protect their assets using deterrent methods. To do this, they carried out improvised patrols with nets and occasional shots into the air. But the emu’s size, speed and endurance were much greater than the farmers could imagine. They viewed them as an unexpected and impossible enemy to control.

In desperation, the colonists made formal requests to the federal government: “Send in the army. This is an invasion!”they exaggerated. And under intense political pressure, the government agreed.

Behind the decision to send machine guns into the Australian countryside were officials, settlers and soldiers who faced a problem that overwhelmed them. The Defense Minister, George PearceUnder pressure from angry farmers and fearing a social outburst, he authorized the deployment of soldiers to Western Australia. He saw it as a quick solution to the producers’ concerns and not a formal act of war. He ordered two machine guns to be sent Lewis (Weapons from the First World War), a detachment and 10,000 bullets to stop the destruction of crops. The target was the birds.

The settlers, many former combatants, were most at risk. Including, James Mitchella farmer and local leader who described the arrival of thousands of emus as a catastrophe that brought them to the brink of ruin. The birds had simply figured out that wheat fields were a rich resource and easy food. Although they acted out of survival rather than aggression, the colonists didn’t care.

The commander of the operation was the major George Pearce Winslow Meredithof the Seventh Light Artillery Regiment. He was given the task of destroying the animals, although he was surprised: he had never been trained to deal with wild animals. On November 2, 1932, Meredith and his men arrived in the region expecting a short and simple operation. But right from the start they realized that nature would not obey military plans.

The first attempt was an eloquent failure. The soldiers approached a herd, prepared their weapons, fired… and the emus fled with incredible speed, scattering like drops of water on glass. Yes, they did not rely on their cunning and sophisticated instincts to survive in an environment that had become hostile. Bullets ran out, the terrain made progress difficult, and the weapons jammed. The army, accustomed to human combat, could not foresee the behavior of such a free and unpredictable animal species.

In an extravagant attempt, they mounted a machine gun on a truck to fire on the move. But the vehicle couldn’t keep up with the speed of the birds, which simply ran away without understanding what was happening around them or why they were being chased. It was irresistible to the press: the scene brought mocking headlines and the name that would go down in history, The Great Emu War Wave Great Emu War.

After the first fiasco, the campaign was temporarily suspended. But pressure from farmers desperate to save what was left of their crops forced the government to issue a regulation second phase. By this point, both Meredith and his men understood that they were not dealing with an “enemy,” but with animals that were extremely adapted to their environment. a native species that had lived in the region for around 40,000 years and was just trying to survive, just like the settlers.

Distributing their weight on long, elastic legs, the emus could change direction without warning and reorganize themselves into small groups, making any ambush difficult. Its dense plumage absorbed minor shocks and its ability to continue running even when injured impressed Meredith himself, who wrote in a report: “If we had a battalion of soldiers with the resistance of emus, we could take on any army in the world.”.

The second phase began on November 13, 1932 with greater planning: They planned ambushes, looked for better positioning, and set up surveillance in areas with regular traffic. About a hundred emus were killed in this unequal battle. But the scale of the natural phenomenon was still overwhelming. Without any conscious strategy and without any intention of confrontation, the birds simply continued on their migratory routes and looked elsewhere for water and food.

Meanwhile, public opinion was divided between ridicule and outrage. The press made fun of it With each new update to the operation, criticism of the government mounted for spending military resources fighting a native species that was merely following its natural cycles.

By December the wear and tear was complete. The army no longer wanted to take part in an operation that exposed it to ridicule; farmers were still in crisis; And the government knew that its insistence would only add to the humiliation. On December 10, 1932, he announced the end of the campaign.

The war was over and the emus won. Australia refused to continue a fight that should not have taken place.

After the military withdrawal, the state chose more rational and less violent solutions: Wiring improvements and agricultural programs to prevent future damage. Over time, these measures proved to be more effective and less destructive than any other weapon. Life in the countryside remained hard and farmers continued to demand support for years to come. Many of the veterans who settled on this land eventually abandoned their farms; The Great Depression hit harder than any flock of birds.

The emus, for their part, continued to migrate, live and reproduce in their natural habitat, unaware of the human narrative that had made them “enemies.” The species thrived and today its ecological value on the planet is recognized: They spread seeds, control vegetation and are an integral part of the Australian landscape.

Today, The emu is a protected species under Australian conservation laws, although hunting is regulated. There are no longer extermination campaigns like in 1932, and although tensions still exist in some rural areas between producers and these native birds, conflicts are being addressed through environmental controls and nonlethal strategies. He no longer feels threatened and continues to travel large parts of the country, knowing that his presence in this area is thousands of years older than any human frontier; and continues to naturally inhabit large areas of Australian territory.