La Casona de Tudanca (Cantabria) maintains one of the richest libraries in Spain in copies of the poetic group of 27, many with autograph dedications on their pages. so that José María Cossío House Museum constitutes, in these years … before the centenary, a rich source for researchers and literature lovers. Among these hundreds of documents is the manuscript of “Crying for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías” by Federico García Lorcaone of the capital elegies of Spanish literature and in which the poet from Granada deplored the brutal death of the Sevillian bullfighter (a few months earlier, captured in Manzanares), friend and unifier of the group with his invitation to Seville in December 1927.

The cancellation of the right-winger by the Ministry of Culture in the Commission for the celebration of the anniversary, denounced by this newspaper and then denied by Urtasun, triggered a flood of reactions contrary to this position and of “adhesions” to a fundamental figure of the silver age of Spanish culture. This is the case of the Seville City Council, as the sole sponsor of the conference ‘Sánchez Mejías, an illustrated bullfighter for the silver age’which will be held on December 9 and 10 at the Real Academia Sevillana de Buenas Letras and will bring together specialists such as Eva Díaz Pérez, Juan Carlos Gil, Andrés Amorós, Manuel Romero Luque and Antonio Fernández Torres, among others.

This report also caused joy among supporters and family friends, proud that the name of Sánchez Mejías was put in the front line, in addition to being a bullfighter, playwright, aviator, patron and even president of Betis. One of them is Ignacio de Cossío Pérez de Mendoza, journalist, writer, businessman and diplomat, nephew of José María de Cossío, academic and author of the El Cossío Encyclopedia. The professor Rogelio Reyes Cano mentioned in the aforementioned report that the union of Alberti, Lorca, Damaso Alonso, Jorge Guillén, Gerardo Diego and José Bergamínamong others, with the professor of Pino Montano was possible thanks to the intercession of the literary critic. In fact, in Tudanca there are several proofs that if Sánchez Mejías was the one who invited the group to celebrate the tribute to Góngora at the Ateneo de Seville on the occasion of the third centenary of his death, it was Cossío who brought them together “one day at the Palace after an afternoon of bullfighting”. However, it was that of the editor, friend of young poets and right-winger, who was the most notable absence from this trip transmitted to posterity.

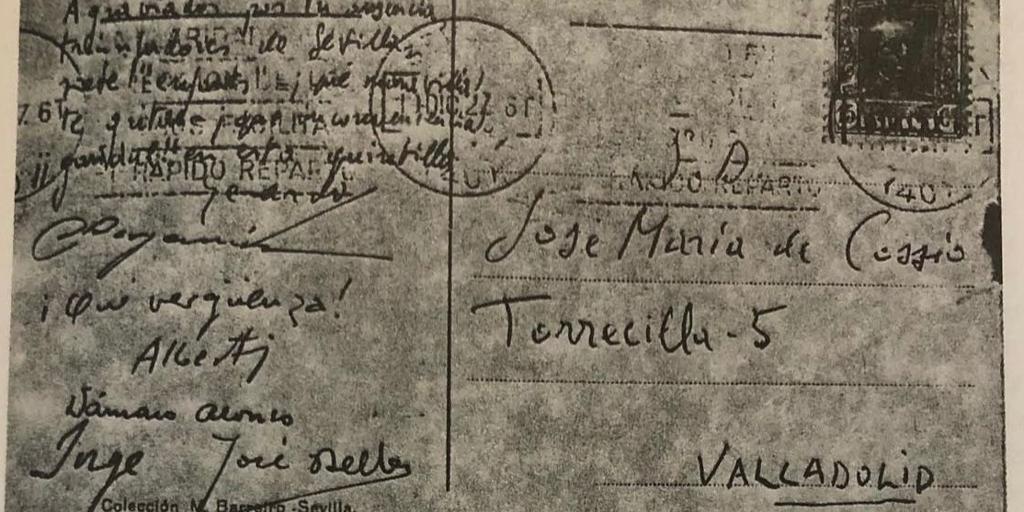

“Injured by your absence, triumphant of Seville”, seven “children”, how wonderful! They yell at you, what an inconvenience! lazy!! in this quintanilla. Gerardo, Bergamín, what a shame! Alberti, Dámaso Alonso, Jorge, José Bello”, they sent Cossío from Seville to Valladolid on December 19 of the same year. The critic didn’t go south because he had to accompany his sisterwho was due to undergo cataract surgery at the time. But it has always been present in everyone’s memory, and the postcard is another of the papers that reflect those “crazy” days and nights in the capital of Seville, sponsored by Sánchez Mejías and in the farm that belonged to Joselito El Gallo.

José María Cossío was unable to attend the Ateneo meeting because his sister was undergoing cataract surgery

“Ignacio, his whole family, was very restless, very knowledgeable about the world. He understood life with a certain genius, he was even a chronicler of his own bullfights, and with talent. He was a character very ahead of his time,” explains Cossío Pérez de Mendoza, who bears the bullfighter’s first name, another example of the affection that the academic always had for his unfortunate friend.

-kNYE--758x470@diario_abc.jpeg)

-kNYE--278x329@diario_abc.jpeg)

The bullfighting writer and academic also received letters of condolence from these poets upon the announcement of the death of the author of “No reason.” And above all the manuscript of “Llanto a la muerte de Sánchez Mejías”, which Lorca sent him and later asked Cossío to contribute to a theme, as he had already done with Villalón, Alberti, Bergamín and Aleixandre. “Do it by return mail. “The poem cannot be released without this requirement,” he orders her in a farewell letter that shows the special relationship between the two: “I have not met a more energetic man than you!” he writes accompanied by some of his classic drawings. “honorary bar”a position that Lorca and the members of the theater company had entrusted to Cossío a few years ago during his visit to Tudanca.

A few months later, in August 1935, García Lorca sent the publisher a dedication in the original autograph from the Palacio de la Magdalena, in Santander. “To my dear José María: this is the true and only dedication that I make to you, in the memory and love of our Ignacio,” he summarizes, accompanying the text with a drawing of a crying harlequin. “Imagine what it was like for my uncle to receive this manuscript, to caress Federico’s tears,” recalls Ignacio de Cossío Pérez de Mendoza of the impact the loss of his friend had on the academic.

In the following weeks, Lorca spoke with José María de Cossío and, according to him, made the decision with him to write a work for cinema about the bullfighting festival which, however, was never made. “Spain owes a lot to Sánchez Mejías. For literature, of course, but also for bullfighting. It could have been another time, but it was that day. The puzzle then fell into place, it was something unique and unrepeatable that would not have happened otherwise,” he explains about the meeting in Seville and the previous presentation at the Palace.

Monument to Ignacio Sánchez Mejías at the San Fernando cemetery in Seville

A first meeting that other members of the Generation remember in their correspondence with the publisher. Rafael Alberti, who was even hired as banderillero by Sánchez Mejías himselfhas always maintained the flame of his friendship with Cossío and the Sevillian family of the bullfighter. “The bullfighting enthusiasm of José María de Cossío, a new friendly acquisition of our Gongorin meetings, led me one afternoon to meet in the hall of the Palace Hotel an exceptional man who would be, after his horrible death, the hero of one of the best elegies,” he writes in another document kept in the house museum of the Cantabrian valley of Nansa. He recounts the impression that the bullfighter made on him, “in his physical maturity”, and how Cossío, “passionate by my verses”, asked him to recite them to him. “I started. Sánchez Mejías listened to them attentively, with a smile on his manly face,” he continued before writing the verses he dedicated to him: The sun spirals and the rivers come in, drenched in bulls and pine forests, attacking boats and ships..

In “The Lost Grove”, the poet from El Puerto de Santa María recounts this anecdote with greater profusion. Before the moment of the story, “Ignacio hugged me and asked a hotel waiter for a good bottle of manzanilla”, and after: “What a brute! – he commented, interrupting me, but indicating with his hand that I continued. After finishing the recitation, I told him that this expression, in the mouth of a man who had fought and killed more than seven hundred bulls, not only seemed right to me but also filled me with pride. Alberti, who boasted of being the first of his generation to befriend Sánchez Mejías (this is what he wrote to Cossío when he sent him the poem. ‘I will see you and I will not see you’ dedicated to the Sevillian), he perceived it from the first moment: “What an extraordinary and intelligent man this bullfighter is! What a rare sensitivity for poetry, and especially for ours, which he loved and encouraged with enthusiasm, already a friend of all!