From the depths of the ocean to the ends of the Universe. From the rewriting of our DNA to the latest Chinese revolution in Artificial Intelligence. The magazine “Nature” has just published its traditional list of the ten most notable personalities of the year in the … various scientific fields. It is not a competition, nor a ranking, but a “map” which allows us to see where humanity is going.

This year’s list is not just a compilation of academic achievements, but includes unsung heroes, data detectives, explorers of dark worlds and, for the first time, a baby who made history. Nature editor Brendan Maher sums it up: “This year’s list celebrates the exploration of new frontiers and the promise of revolutionary medical advances. »

Tyson and the digital eye that detects dangerous asteroids

Let’s start by looking up. High up, to the arid peaks of Cerro Pachón, Chile. There sits the Vera Rubin Observatory, a time machine that promises to give us the best views ever of distant galaxies. It’s a true giant that cost $810 million, and behind it is Tony Tyson, a physicist from the University of California who has been dreaming of this moment for three decades.

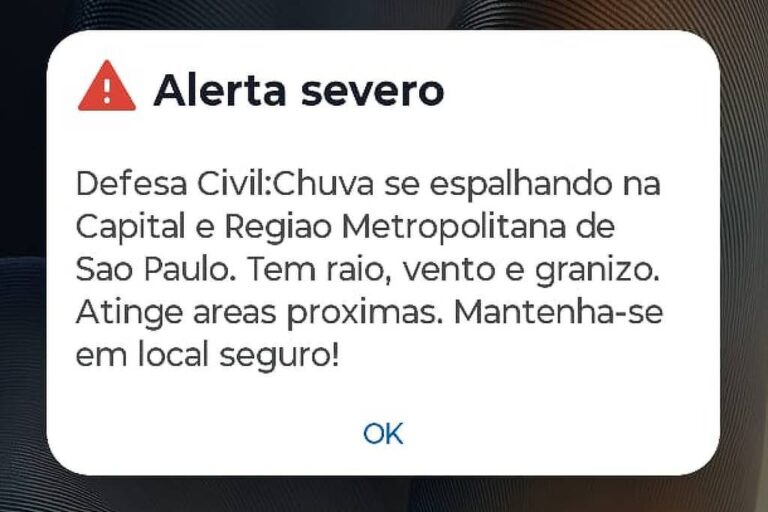

Tony Tyson, physicist

Tyson not only designed a telescope, but also encouraged the creation of the largest digital camera ever built, a 3,200-megapixel “beast” that is the size of a utility vehicle. Its objective is ambitious and titanic: to map invisible dark matter in 3D and create a continuous “video” of the southern sky. “It was high risk, high reward,” Tyson confesses. Today, at 85, this pioneer has achieved what seemed impossible: opening a digital eye capable of detecting dangerous asteroids and distant supernovae every 40 seconds.

The Oceanic Underworld of Mengan Du

Meanwhile, and at the same time that Tyson was looking at the stars, Mengran Du was looking down, just in the opposite direction, towards the depths. It is not for nothing that this geoscientist from the Chinese Academy of Sciences has become the great explorer of the oceanic “underworld”. On board the submersible Fendouzhe, he descended into the Kuril-Kamchatka trench to a depth of 9,000 meters.

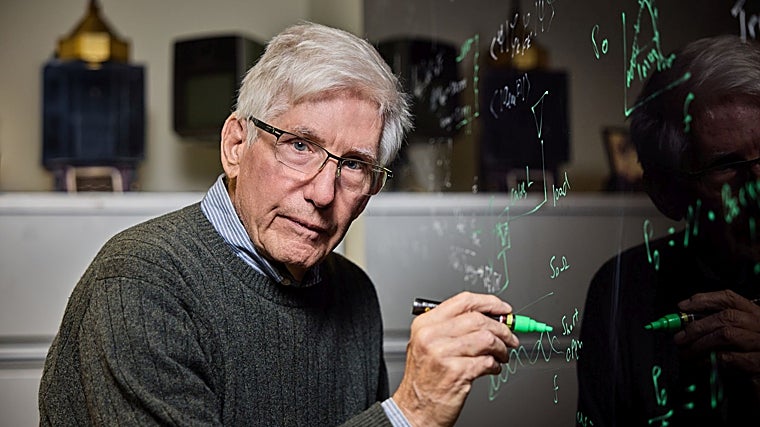

Mengran Du, geoscientist

And what he discovered there amazed the world: the deepest ecosystem ever discovered, a vibrant animal community thriving in total darkness. Red tube worms and strange creatures that rely not on the sun, but on chemosynthesis, and feed on methane and hydrogen sulfide. With this discovery, Du confirmed the existence of a “global corridor” of deep-sea life that connects Earth’s oceans, a discovery that requires rewriting the marine biology books.

Kj Muldoon, the example that DNA can be corrected

If space and the ocean mark our physical limits, genetics are their inner boundary. And this is where 2025 takes our breath away with two different stories, but they have a lot in common.

KJ Muldoon was born with an ultra-rare genetic disease that sentenced him to death

The first has a baby name: KJ Muldoon. You may remember his photo, of a chubby, smiling boy from Philadelphia. KJ was born with a death sentence: an ultra-rare deficiency (CPS1) that prevented his body from processing proteins, thereby building up deadly ammonia in his blood. There was no cure, until a team of visionary doctors decided to try the impossible: “hyper-personalized” gene editing therapy. To achieve this, they used a variant of CRISPR to correct a single faulty letter among the baby’s 3 billion base pairs of DNA. KJ is living proof that genomic medicine is no longer science fiction; It’s a reality that walks and smiles.

Sarah Tabrizi, for slowing down Huntington’s disease

The second story takes place across the Atlantic, in London, where neurologist Sarah Tabrizi has achieved what has been expected for decades in the field of neurodegenerative diseases. Huntington’s disease is devastating, an inescapable genetic sentence.

Sarah Tabrizi, neurologist

However, Tabrizi led trials of a gene therapy (AMT-130) which showed, for the first time, that it is possible to slow the development of the disease. “The dial has moved,” she says cautiously but with emotion. Its success, reducing clinical deterioration by 75% compared to the control group, is not just information; This is life time saved for thousands of families.

Liang Wenfeng to democratize AI

2025 will also be remembered as the year China shook up the technology game. The person responsible is Liang Wenfeng, a financier turned AI wizard. In January, his company Deep Seek launched the R1 model. The surprise? Not only did it perform as well as the best American models, but it was built with only a fraction of the resources invested by large companies and, more importantly, it was released as open source. Which means anyone can download it and use it.

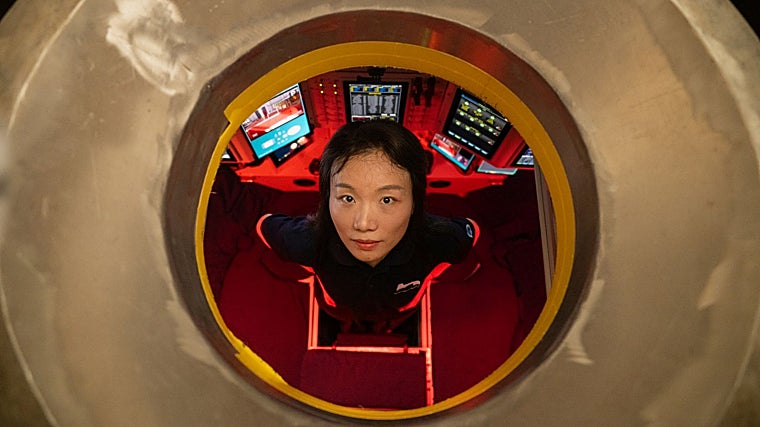

Liang Wenfeng, financier

In other words, for Nature, Liang’s merit lies in having democratized “superintelligence”, breaking the monopoly of large Western technology companies and demonstrating that efficiency and open source can compete with the giants of Silicon Valley.

Achal Agrawal, the bad science detective

But technology without ethics is dangerous. And that’s where Achal Agrawal, an Indian data scientist turned “retraction detective,” comes in. There is no doubt that what Agrawal did has great merit: he sacrificed his academic career to expose the “epidemic” of plagiarism and fraud that has affected academic institutions in India.

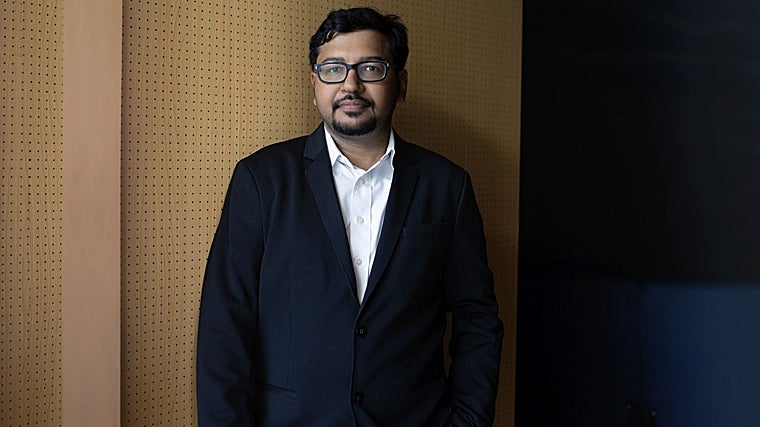

Achal Agrawal, Data Scientist

Their work, often solitary and costly, ultimately forced the Indian government to radically change the way it ranked universities, ultimately penalizing malpractice. A reminder that integrity is the pillar on which all science must rest.

Precious Matsoso: health for all

In a world that recently suffered its latest global pandemic, Nature decided to include Precious Matsoso on the list of 10. From South Africa, this health diplomat achieved what seemed impossible after years of tense negotiations: the first global pandemic preparedness treaty.

Precious Matsoso, Health diplomat

Matsoso had to confront both national selfishness and the deeper distrust between the North and South of the planet to forge an agreement that guarantees, or at least promotes, that vaccines and treatments reach everyone the next time a virus threatens us. Matsoso even sang The Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love” in front of delegates to break the ice. And it worked.

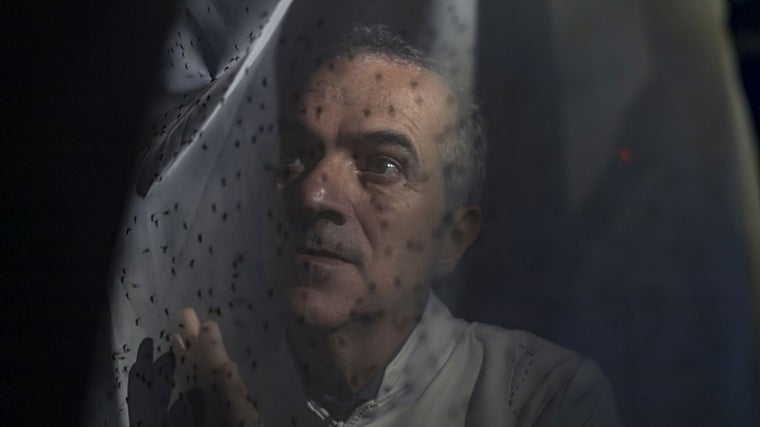

Luciano Moreira who fights dengue fever with mosquitoes

In the same public health trench, but in Brazil, we find Luciano Moreira. His approach is worthy of a science fiction novel: fighting diseases transmitted by mosquitoes… with more mosquitoes. Moreira inaugurated the first mass factory of mosquitoes infected with the Wolbachia bacteria, which makes them incapable of transmitting dengue fever. By releasing millions of these insects, Moreira managed to replace the population of dangerous mosquitoes.

Luciano Moreira, public health specialist

The results in cities like Niterói, where dengue fever has decreased by 89%, are indisputable. Moreira doesn’t just do science; is in the process of “manufacturing” public health on an industrial scale.

Yifat Merbl and the value of cellular waste

Israeli systems biologist Yifat Merbl also made Nature’s list. A scientist who decided to look where no one looks: in the “waste” of the cell. So, by studying proteasomes (the cellular protein grinders), Merbl discovered that not only do they recycle waste but that, under certain conditions, these machines can cut proteins to create antimicrobial peptides that fight infections.

Yifat Merbl, biologist

This is essentially a completely new and unexpected facet of our immune system that has been hidden in plain sight.

Susan Monarez vs. Trump

Finally, the list ends with a case of political courage in the United States. Susan Monarez, a microbiologist and immunologist, has stood firmly against the Trump administration. As director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), she refused to follow orders from U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to fire the agency’s top scientists and approve vaccine recommendations without first considering relevant scientific data. Monarez was only in power for a month, but he showed that sometimes the most important scientific act is to say “no” to power when the evidence says otherwise.

Susan Monarez, microbiologist

Together, these ten profiles tell us something important about science in 2025. They tell us that knowledge, like truth, is not a straight path, but strewn with pitfalls, like Tyson’s telescope; of sacrifices, those of Agrawal or Monarez. But also a pure marvel, like Du’s verses or little KJ’s smile.