(SUMMARY) The five months that Orson Welles spent in Brazil in 1942 constitute one of the most intriguing periods in the history of world cinema. The 26-year-old filmmaker, then at the height of his success with his “Citizen Kane,” arrived here as part of the United States’ good neighbor policy toward Latin America during World War II. The white film that was expected of him, however, became a radical project, a mixture of fiction and documentary, on Brazilian reality, in particular on the black population, which displeased both the American government and Getúlio Vargas. Although never completed, the production changed the course of Welles’ career and anticipated the stylistic resources of modern cinema, a book by an American scholar argues.

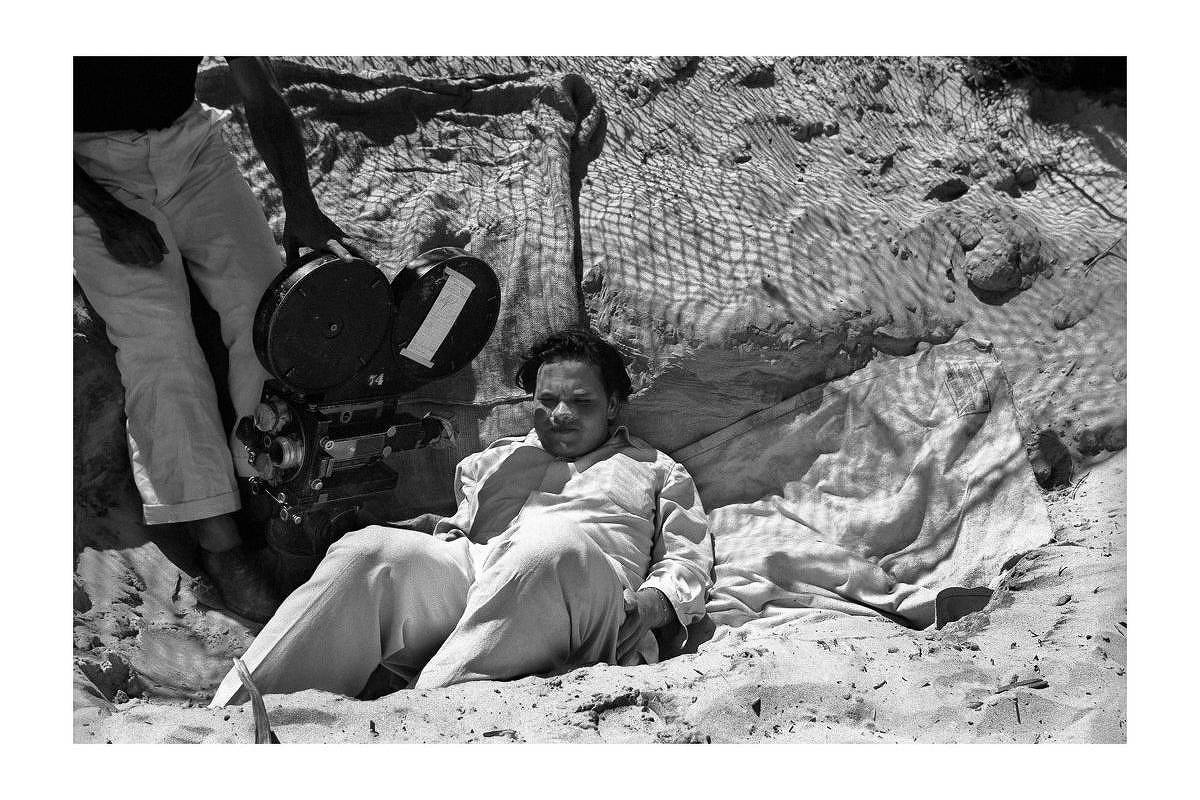

February 1942. Orson Welles, great prodigy of North American arts, director of “Citizen Kane” and man who frightened the United States with the radio version of the book “War of the Worlds”, arrives in Rio de Janeiro to film the Rio Carnival with great fanfare.

Five months later, he left the country discreetly, involved in numerous controversies. His second fiction feature film, “Soberba” (1942), was re-released against his wishes and the project he had made in Brazil had an uncertain future. The visit to Brazil constitutes the decisive episode in Welles’ career, at least in terms of his public image and his relations with the major American studios.

Over the years, these months have been the subject of many discussions and contradictory discourses. Brazilian cinema has even dedicated films to him like “Nem Tudo É Verdade” (1986) and “Tudo É Brasil” (1998), both directed by Rogério Sganzerla, or more recently “A Jangada de Welles” (2022), by Petrus Cariry.

Unesp recently published “It’s All True: The Pan-American Odyssey of Orson Welles”, which researcher Catherine L. Benamou published in the United States in 2007. It is by far the most serious and detailed work on Welles’ months in Brazil, and its availability in Portuguese is excellent news.

Benamou’s text is careful and constructed from available materials and evidence. “It’s All True,” the project Welles came here to film, was never finished, although we have a documentary of the same name from 1993, made from the raw material from the era.

Benamou uses everything Welles left from the project, from scripts to images to available documentation, as well as extensive research in the United States, Mexico and Brazil. It is part historical work, part critical study of a suppressed film.

Some elements of the “It’s All True” saga are well known: Welles came to Brazil as part of the Good Neighbor Policy that the U.S. government developed during World War II to keep Latin American countries aligned with its interests; the RKO studio, where he worked, was sold to an owner less sympathetic to the director; Estado Novo’s dissatisfaction with the direction the project was taking.

Benamou fills in many gaps to better develop these ideas. For example, Welles’ friendship with American photographer Genevieve Naylor, who was already in Brazil as a cultural ambassador at the time and who not only shared many of his interests, but helped bring him closer to the samba dancers of Rio.

The researcher strives to overcome the difficulties of Brazilian filming and to think about the “It’s All True” project as a whole. It was a radical idea mixing documentary and fictional elements, far from the docudrama of the time. Echoes of what Welles was looking for can be seen in post-war cinema or even in the films that Iranian Abbas Kiarostami would make in the early 1990s.

The idea was a film in episodes in which each of them would be inspired by real events and would develop in a mixture of dramatizations and documentary elements. Welles and his collaborators examined seven different episodes that moved in and out of the film over time.

In addition to the two Brazilian sections, with Carnival and the history of the Jangadeiros of Ceará, we even filmed parts of a Mexican episode, “Meu Amigo Bonito”, about the relationship between a boy and a bull.

Before filming Carnival, for example, Welles and his collaborators developed a film on the history of jazz, based on the autobiography of Louis Armstrong, which would star himself and serve as an entry point for commenting on the origins of the genre and its aesthetic and sociological relationships. Certain principles will be used for the samba film, with Grande Otelo as master of ceremonies.

Benamou provides ample space for the existing record of each of the episodes, including, where possible, the reconstruction of his arguments in detail. This is particularly useful in the Carnival episode, which Welles worked on for months, but whose raw footage is in worse shape than the scenes with the chevrons, which had much more space in the 1993 documentary and in the iconography of the project.

“It’s All True” began as a U.S.-centric production before gaining momentum. This was part of the US government’s desire to bring the countries together and, above all, to please Getúlio Vargas.

The “Pan-American Odyssey” of the book’s subtitle says a lot about how the project was transformed, by Welles’s will, into a film about the American continent, well beyond the more utilitarian political function of the Roosevelt administration. Benamou recalls that at the time Welles was dating Mexican actress Dolores del Rio and that the idea of a Pan-American film appealed to him given his internationalist interests.

The book contains rich documentation on Brazilian episodes and their political aspects. Welles may have arrived in Brazil as a cultural ambassador and his filming of Carnival, in particular, was seen by the Vargas government’s propaganda department as not only an official film, but also a tourism promotion to American audiences.

A supposedly direct film which gradually took on new contours given the American filmmaker’s desire to listen to the Brazilians with whom he came into contact and to explore the country.

Welles arrived here on the eve of Carnival, filmed the celebrations, and spent the next few months filling in the gaps and better understanding the social phenomenon he observed. Benamou places great emphasis on the collaborative aspects of the film and, despite the filmmaker’s strong personality, he sought to integrate the Brazilian voices he encountered during his trip, even if they sometimes contradicted the initial objectives of the work.

The political dimension is clear in the Jangadeiros episode, which recreates the trip of a group of fishermen from Ceará to Rio to protest working conditions, an event that received good media coverage at the time.

Benamou also highlights how the same concern manifests itself in the Carnival extracts, notably in the use of the samba “Adeus, Praça Onze”, written by Herivelto Martins and Grande Otelo, whose presence should be recurring in the film.

Welles wanted to reinforce the protest aspect of the samba composed to celebrate Praça Onze at the time of its destruction, in the process of gentrification of the city. The idea of samba as central to the city’s black community and its place in Rio’s urban space proves to be at the heart of the project, and Benamou highlights Welles’ difficulties since his intention to open the film in the hills and favor the music’s popular origins rather than spaces like Cassino da Urca.

The book highlights the resistance to the project from the Vargas government and especially from the American studio, very unhappy with the emphasis placed on the black Brazilian population.

Reports on Welles’ time in Brazil, even the most sympathetic ones, tend to focus on his impact on the director’s later career, shifting the film towards his figure.

The great merit of Benamou’s book is to celebrate “It’s All True” as a project in itself. Its importance begins with its aesthetic and political ambitions, and its tragedy is the suppression of the work and all the possibilities it suggests.