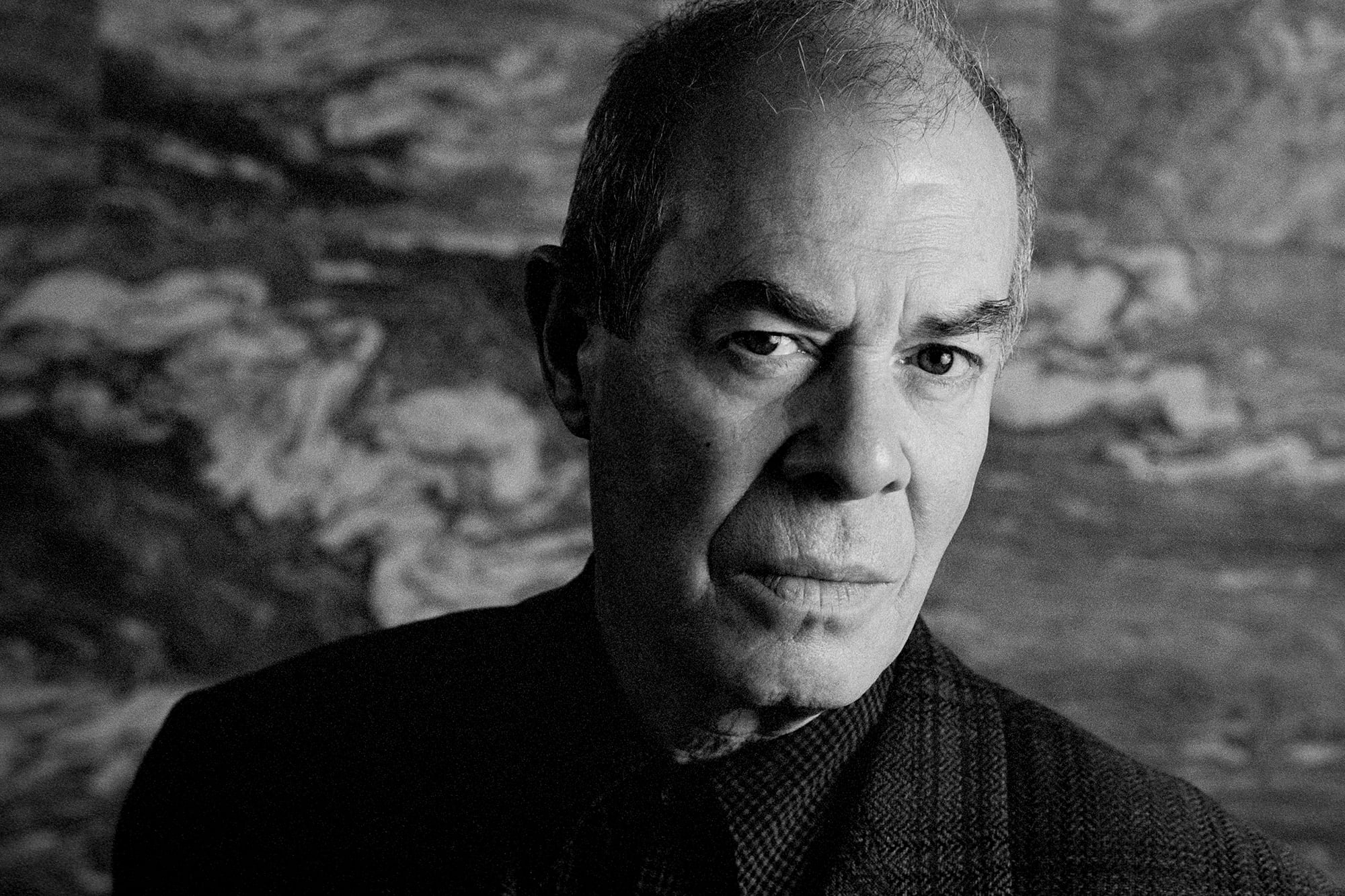

Hans van Manenformer dancer and choreographic director of the Dutch National Ballet for more than 50 years, where he created more than 150 avant-garde works for his dance company, He died yesterday at the age of 93. Van Manen’s death was announced in a statement by Ted Brandsen, director of the Dutch National Ballet.

In his choreographies Van Manen fused classical ballet with contemporary movement techniques, creating a simple, abstract style that earned him the nickname “Mondrian of ballet.”. Because of his succinct narrative, he was also nicknamed “the Harold Pinter of dance” as well as “the Versace of dance” because his work was sometimes full of homoeroticism.

But none of this fully applies to her work, as Anna Kisselgoff, then dance critic for The New York Times: “The pleasing thing is that he is himself: the Hans van Manen of dance,” wrote Kisselgoff. During his long career, Van Manen worked as resident choreographer for two of the Netherlands’ leading ballet companies: in addition to the Amsterdam-based National Ballet, he worked for the Nederlands Dans Theater in The Hague.

His choreographies have been performed at numerous major venues outside his country, including the English Royal Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet, the Stuttgart Ballet and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in New York.

Van Manen’s dance career began in the early 1950s during the post-war avant-garde wave and spanned eight decades. The choreographer continued to attend rehearsals well into his 90s and maintained a prominent presence in the Dutch cultural milieu.

A life like something out of a Dickens book

Hans Arthur Gerard van Manen was born on July 11, 1932 to Gustav van Manen and Marga Lilienthal in Nieuwer-Amstel, a suburb of Amsterdam now known as Amstelveen. His father had grown up in Germany, his mother was a German citizen and they had married in Germany in 1926. A year later, when both were 19, they had Guus, their first child.

Due to financial problems, the family moved to the Netherlands before Hans was born and moved at least a dozen more times before the boy turned five. His father sold scrap metal to survive and later found work as a cosmetics salesman. When Hans was 5 years old, he died of tuberculosis and the family sank into complete misery.

The older brother Guus, now a teenager, lived alone, and Hans and his mother found an apartment in a building next to the Stadsschouwburg, the city theater.

“The other two floors of our building were all prostitutes, so it was actually a kind of brothel,” explains Sjeng Scheijen, author of the biography 2024. Gelukskind: Het leven van Hans van Manen (“Lucky Boy: The Life of Hans van Manen”). “From that moment on, his story seems straight out of a Dickens novel.”

Hans did odd jobs for “the ladies,” as he called the prostitutes, so he could buy food and firewood to heat the house while his mother worked as a stenographer. Schools were occasionally closed during the Second World War. “Basically I was a street child,” says Scheijen. But he also found a way to satisfy himself and be happy.

“Since I was 7 years old, all I wanted to do was dance,” Van Manen said in a 2018 interview. “I performed in the living room and listened to live recordings from the Concertgebouw,” he said, referring to the Amsterdam concert hall.

In the final year of World War II, the Netherlands suffered a trade blockade that triggered a famine known as the “Hunger Winter.” The schools closed and Hans never returned: his formal education was over at just 11 years old, but for decades he continued to expand his cultural horizons through his work and personal contacts.

Her mother got her a job as an assistant hair and make-up artist in the Stadsschouwburg. Hans really enjoyed the work and won a national award for hair and make-up at the age of 16. Two years later, after attending a rehearsal of the ballet evening directed by choreographer Sonia Gaskell, the young man asked if he could join the company. Gaskell agreed to train him once a week, but in the end there were arguments. “He fired him a few months later,” he says. “He told him nothing would ever come of it.”

Hans immediately began studying with another pioneer of Dutch modern ballet, Françoise Adret, ballet director of the Dutch National Opera.

Gaskell later invited him to return and gave him his first opportunity to perform as a professional dancer in 1951. Four years later he created his first choreography for Olé, Olé, the margaritaa variety magazine by the Dutch singer and actor Ramsés Shaffy, and the following year he created his second work, swingfor the Ballet Scapino in Rotterdam. His third piece, for the production of the opera Festive dish of the Dutch National Ballet, won the State Prize for Choreography in 1957.

As an artist, the young Van Manen was heavily influenced by various cultural figures with whom he was friends, including the Dutch designer and artist Benno Premsela and the American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

Premsela became known for speaking openly about his homosexuality on Dutch television in 1964, and van Manen, who had told his mother that he was homosexual as a teenager, became actively involved in the gay rights movement in the Netherlands. In the 1970s she met photographer and videographer Henk van Dijk, whom she married in 1999, the year the Netherlands legalized same-sex marriage. Van Dijk survives him.

Van Manen maintained a circle of friends and collaborators who accompanied him over the years and included the designer Keso Dekker, the photographer Erwin Olaf and the ballet dancer Rob van Woerkom.

After living for a short time in Paris, where he worked with Roland Petit’s dance company, In 1960 Van Manen moved to The Hague to join the Nederlands Dans Theaterthe new company founded by two of Gaskell’s followers: the famous Dutch ballet couple Alexandra Radius and Han Ebbelaar. From then on van Manen was He was the company’s resident choreographer and artistic director for ten years.

His best-known choreographies from this period include his ballet from 1963, Symphony in three movementsthe first of eight pieces with music by Stravinsky, generally considered his great choreographic “revolution.” From then on he created one ballet after another, and by 1971 he had already produced more than 35 productions.

Van Manen used to say that his biggest influence was George Balanchine, but he also incorporated the technique of Contraction and relaxation by Martha Graham as well as more informal forms of popular dance, such as tap dancing by Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly.

Van Manen joined the Dutch National Ballet in 1973.where he took on the position of resident choreographer and worked with artistic director Rudi van Dantzig. The main dancers in the theater at that time were the married couple Radius and Ebbelaar. Van Manen’s successful ballets include: Fortepiano Adagiofrom (1973) and 5 tangos (1977), two creations that have been performed repeatedly since then.

In 1987 he returned to the Nederlands Dans Theater as resident choreographer and remained there until 2003, when he again became resident choreographer of the National Ballet and the National Opera.

Over the years he has won numerous awards for his choreography, including the Erasmus Lifetime Achievement Prize – one of the most prestigious in Europe -, the Grand Prix à la Carrière in France and a Dutch royal award, that of Officer of the Orange Order, awarded to him by King Willem-Alexander in 2018.

In 2023, the National Opera and Ballet organized a dance festival to celebrate the dancer and choreographer’s 90th year.

Even in old age, Van Manen remained an active participant in the world of dance. Brandsen remembers an international tour by the National Ballet a few years ago, during which van Manen stayed up all night partying after a performance.

“In Russia, Hans was like a hero, they treated him like a god,” says Brandsen. “There was a reception after the show, and at 2 a.m., when the bar closed, he said to us, ‘Let’s go to my room.’ He was about 87 or 88 at the time, and I was more ready to go to bed. But everyone went to his room and partied until 4:30 p.m. His vitality was surprising.”

(Translation by Jaime Arrambide)