A rare set of fossilized footprints found in the US state of Colorado may indicate that a giant dinosaur walked limping along a trail during the late Jurassic period, around 150 million years ago. The discovery, analyzed in a study published in the scientific journal Geomatics, brings together more than 130 preserved footprints along a continuous 95.5 meter path at the West Gold Hill dinosaur footprint site, one of the largest ever attributed to a single animal.

- Lunar calendar for December 2025: see the phases of the moon in the month

- 3I/ATLAS: Interstellar comet gives off greenish glow in new images

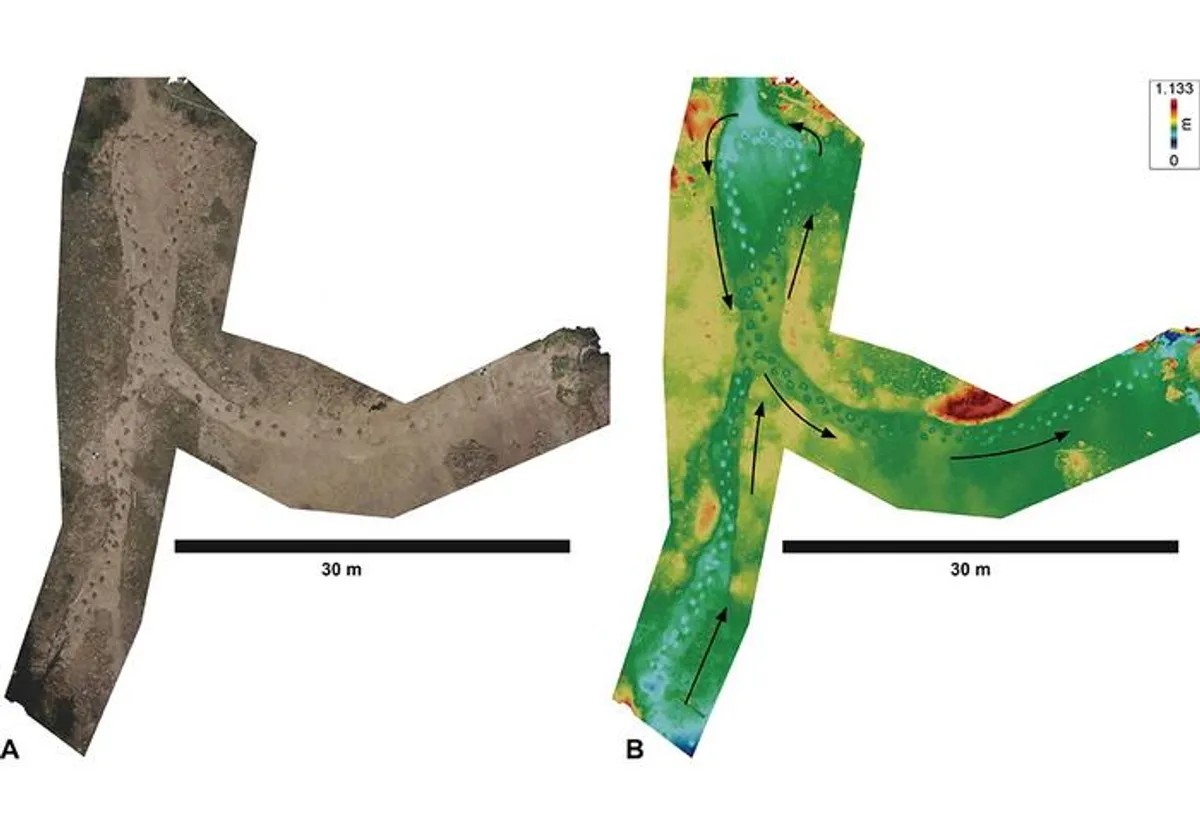

To map the entire trail, researchers used drones, which captured high-resolution images and enabled the creation of a detailed 3D model. The reconstruction revealed that the dinosaur, a sauropod, first headed northeast and made an almost complete turn – forming a “loop”-shaped circuit – then followed again in the same direction. According to scientists, trails this long are rare and offer valuable clues about the locomotion and behavior of these prehistoric giants.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/L/W/eZbA0NRlOCxuvcAVgAFg/sauro-tracks-l.webp)

The footfall analysis showed a difference of around 10 centimeters between the steps on the left and right sides. This detail suggests that the animal would have put more weight on its left paw, raising the possibility of a slight limp, possibly caused by an injury to the opposite side.

The authors emphasize, however, that this asymmetry does not definitively confirm a physical problem and may simply reflect a natural preference in the way of walking.

- “Improbable friendship”: orcas and dolphins reveal unprecedented cooperation in hunting in the Pacific Ocean; to understand

In addition to possible errors, the researchers observed variations in the width of the spacing between the footprints along the path, ranging from narrowest to widest, which may indicate changes in posture or speed during the movement.

“It was clear from the start that this animal started walking northeast, completed a closed circuit, and then ended up heading in the same direction. In this circuit, we found subtle but consistent clues to its behavior,” said paleontologist Anthony Romilio of the University of Queensland, one of the study’s authors.

The footprints are not perfectly preserved, perhaps due to erosion caused by glaciers that removed the upper layers of soil during the last ice age. This prevents accurate identification of the species and even whether the marks were made by the front or rear legs. Nonetheless, the scientists concluded that, with a few exceptions, the prints have a consistent shape and were likely left by the same animal.

- Alert: Floods in Indonesia threaten the survival of very rare orangutan species

According to Romilio, the footprints date back to a period when long-necked dinosaurs, such as Diplodocus and Camarasaurus, inhabited North America. “It dates from the late Jurassic period, when long-necked dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Camarasaurus roamed North America,” the researcher said in a statement. “In addition to its extreme length, this trail is unique because it is a complete circuit,” he added.

Biomechanical data also makes it possible to interpret the observed movement. If the maker of the prints was a Diplodocus, with a greater concentration of weight in the rear part of the body, the radius of curvature could represent the limit of what the animal could accomplish.

A Camarasaurus, with a more forward center of mass and a more vertical neck, might be capable of even tighter curves. Regardless of species, the pattern indicates a dinosaur that distributed more weight over its left leg, reinforcing the possibility of a minor injury.

Scientists admit that it will probably never be possible to know why the dinosaur changed direction so abruptly. Hypotheses include a fright caused by a predator, a territorial encounter with another individual of the same species or a natural event, such as a loud clap of thunder.

The study is open access and expands understanding of how the largest animals to ever walk the Earth moved in their natural environment.