After almost two years of discussions with human rights organizations and no energy for two more years of “culture war,” said the lawyer and former judge Alberto Banos He resigned last Thursday to continue as the government’s undersecretary of state for human rights Javier Mileiin the structure led by the Ministry of Justice, Mariano Cuneo Libarona.

His successor, already determined according to voices from the ruling party and announced this Tuesday, has the difficult task of leading what Balcarce 50 defines as a “new phase” of adjustment in the region, aimed at consolidating an undersecretary whose focus is on the “legal defense” of the country on issues such as freedom of the press or the suppression of demonstrations, and far from “the boxes” that they entrust the management of to human rights organizations.

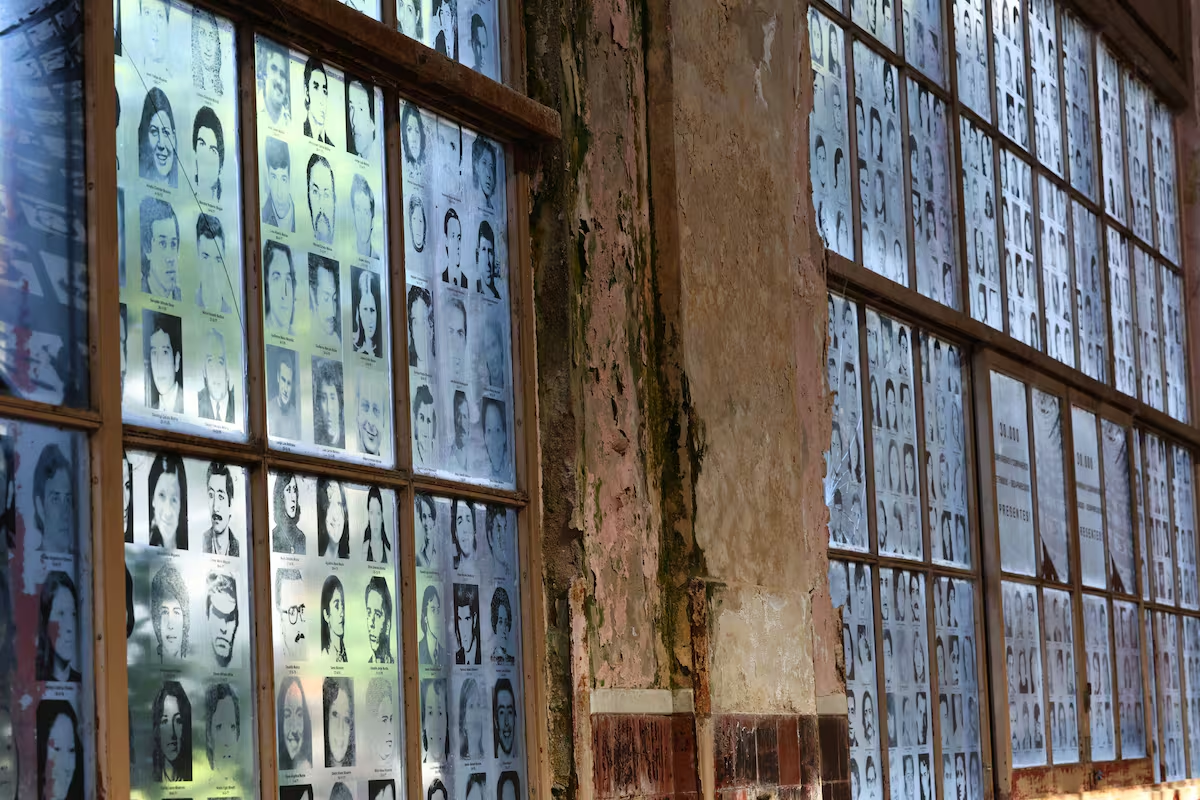

In this context, the organizations denounce that the ideological hostility against them that has prevailed since Milei’s arrival at the Casa Rosada has been aggravated by the progressive shortage of funds and the apparent deterioration of the buildings and activities linked to the memory of the horrors of state terrorism, whose main leaders were convicted by the judiciary on December 9, 1985, exactly four decades ago.

“It is obvious that we do not enjoy their sympathy,” says with irony a key human rights leader who knows the hard everyday life of Baños – who, faced with constant complaints from human rights organizations, arrived at his office, in the headquarters of the former ESMA, in the tripartite Entre, which also forms the government of Buenos Aires and is in charge of managing the 17-hectare property that includes 20 buildings, each given to entities such as the two slopes of Madres de Plaza de Mayo, Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and the group Hijos, among others.

According to official sources, the following generally applies: The annual budget allocated by the government to the entity is $3,908 millionthe same amount it received in 2025 and which includes the payment of salaries of 170 employees, including security, maintenance, management and logistics personnel, as key items. “There is no money for new works or for the maintenance of some activities carried out, not even for the preservation of the buildings,” they say, close to the organizations’ representative, the former deputy of Buenos Aires. Gabriela Alegre.

They count 800 employees laid off in recent months from the ESMA Memory Site Museum, the National Memory Archive and the National Genetic Data Bank, citing as an example the peeling walls and huge leaks that can be seen every day during heavy rain in the Cuatro Columnas building, one of the property’s landmarks.

The Mercosur Human Rights Institute is housed in another building on the property. The former ambassador and parliamentarian of Parlasur Gabriel Fuks states that despite the commitment to support the building and its activities, the Milei government has decided not to make any further contributions, “threatening the fulfillment of the Institute’s main functions.”

Another example: The so-called ESMA Memory Site Museum, which is located in the former secret prison of the last dictatorship and was inaugurated in May 2015, is now only open from Thursday to Sunday, two days fewer than a few months ago.

In the face of criticism, the government assures that those fired are “fighters” and that the organizations “continually demand money” because “a lot of money is invested in every meter of the property”. As a recent example, they cite that “they asked us for $16 million to cut the lawn” and that “we’re providing all of that because the city’s contribution doesn’t even reach 10 percent.” They assure that “the people they ask us for security are excessive, they almost want to have a fortress there,” and they threaten to review the cost of each post, the number of employees and the percentage of contributions from the Buenos Aires government, whose representative in the entity is the current director of human rights of the city. Natasha Steinberg.

In February this year, Baños made headlines when, before a free show by artist Milo J at one of ESMA’s former facilities, he submitted to the court an injunction that could suspend the concert. The reason given was that there was no permit and there were insufficient security measures. In May, by the speaker Manuel Adorni It was announced that the then Minister for Human Rights would move down a step and become Under-Secretary of State, with an estimated savings of $9,000 million per year.

The organizations reiterate that the spending “only covers the bare essentials” and contradicts a recent fact: two buildings on the property were restored in record time to move the AMIA case files there. “It means there is money if they want it,” complain voices from human rights organizations.

The background to the dispute is obviously that there are two opposing views on the events of the 1970s. In his last public speech to the UN Committee Against Torture, Baños declared that “a deal was made from the past that this government will not tolerate.” He stressed, in line with the government, that the idea was to strengthen the “full, neither ignored nor denied” memory of the “thousands killed by the action of the guerrilla militias”, whose relatives – as he made clear – “did not receive any compensation or build any monuments”.

The government assumes that, beyond the imprint that he could give to his office, these will be the principles that will follow the successor to Baños, who took office because of his friendship with Cúneo Libarona, who would in principle leave the government next March.

The mistrust between the government and the organizations is palpable. Of the official event planned next Wednesday to commemorate International Human Rights Day in the former Esma, national officials said only that it would take place in the afternoon, without a guest list or further details.

The organizations, meanwhile, speculate that based on Baños’ words, an offensive will begin aimed at providing compensation to the victims of those killed by the guerrilla actions and granting release to soldiers still serving prison sentences for human rights violations. They associate this information with the consolidation of the Pañuelos Negros group, which is at the top Asuncion Benedictand which, among other things, integrate Lucrecia Astiz, (sister of convicted former sailor Alfredo Astiz) and the libertarian lawmakers of Buenos Aires Rebecca Fleitas And Lucia Montenegro. The contrast with the white scarves of the mothers of the Plaza de Mayo speaks for itself.

“Victims are victims, we understand that. But we, the organizations, are in the former ESMA,” they explain from one of the organizations and are preparing for new fights.