Imagine and test. These words were chosen by social worker Liliane Santos as the subtitle of one of the slides of her postgraduate work in social urban planning at Insper, a higher education institution based in São Paulo. The two terms do not exhaust the subject – far from it, we would have to add verbs like analyze, propose, build, among other possibilities – but they help to summarize a fundamental concept of what social urbanism is: the creation of an urban infrastructure that goes hand in hand with actions capable of improving the daily life of those who live in vulnerable areas of the city.

- Understand Delaroli’s messages in the interview with GLOBO: In Bacellar’s absence, the deputy tries to establish himself as leader and restructure the forces in Alerj

- Chef of Santo Daime: Padrinho Paulo Roberto is accused of sexual rape by fraud against former followers of a Rio church

Liliane, born and raised in Baixa do Sapateiro, one of the 15 favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in the northern zone of the capital of Rio de Janeiro, is one of 19 people from Rio who had the opportunity to take the course, which lasts a year and has welcomed 156 students since its creation in 2020. Like her, a good part of the students of “Rioca” have received scholarships and financial aid from the Manu Institute, since, in addition to commuting and accommodation in São Paulo for four days, once a month you have to pay monthly fees of up to 24 installments of R$2,500 without discounts.

The prototype presented by the student idealizes a new landscape for Rua Evanildo Alves, an emblematic street of the Baixa, on the border with Nova Hollanda, a sort of internal border not drawn, but very well known to all residents due to its history of violence and clashes. A point of natural tension because it serves as a boundary between the territories occupied by different factions, the place, it is no coincidence, began to receive initiatives from Redes da Maré, a civil organization active in the area, whose director, Eliana Sousa Silva, professor and doctor in Social Services, is one of the coordinators of the postgraduate course offered by Insper.

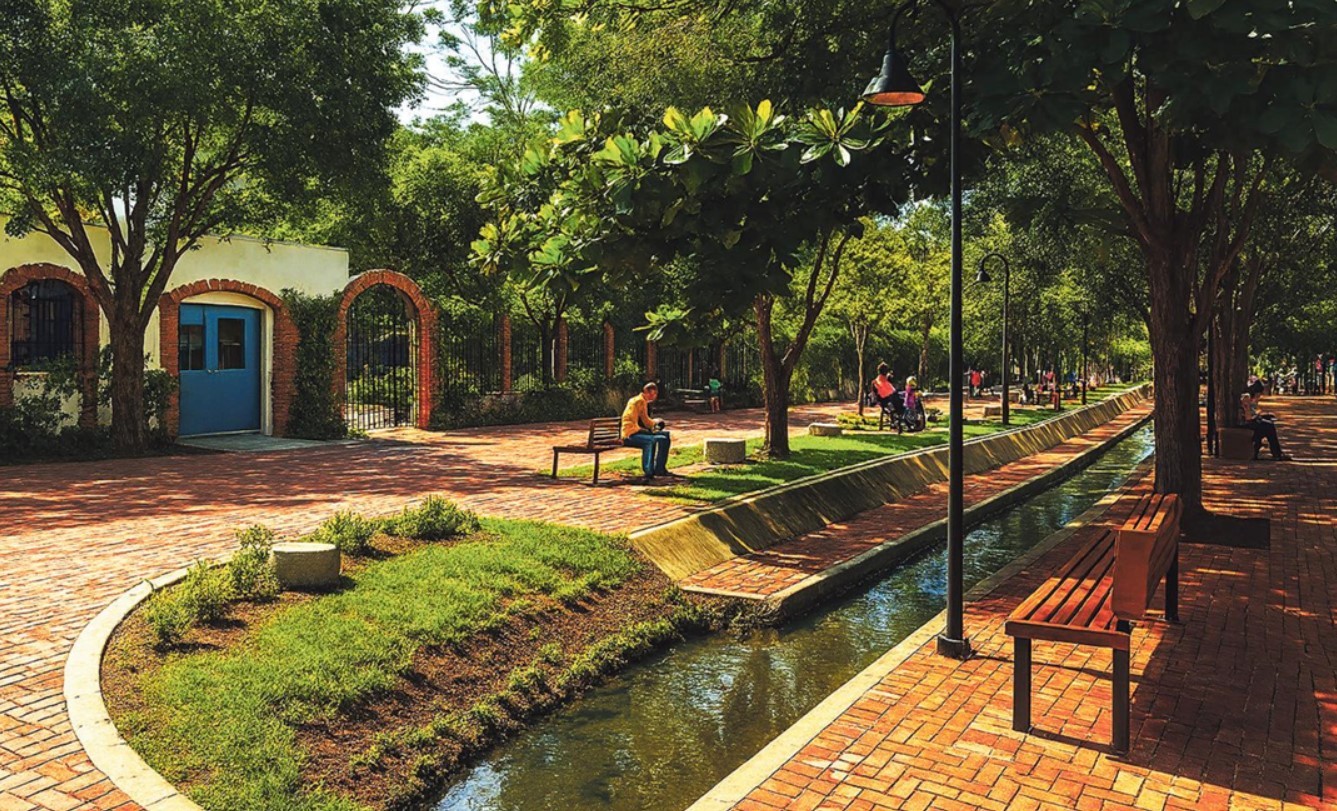

The design proposed by Liliane, with the help of Artificial Intelligence, shows a greener street, with a defined community space, benches and a ditch that transforms into a clean and pleasant watercourse. Compared to the real image, the absence of the high cold wall that separates Ciep Elis Regina from the street is very striking. In its place, a small entrance, an arched portal with exposed bricks and guardrails which allow the visual integration of the spaces.

— I included the grid in the project, but the ideal is that it does not even have that, that it is an integrated space aimed at coexisting with street furniture — says the 37-year-old researcher, who holds a master’s degree in Justice and Security. — I have a very vivid memory of the scenes of violence that I saw there, people being cut up, that’s all. Over time, small actions have been carried out by Redes da Maré and the reality today is different. Small interventions often have more impact than major works.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/j/k/c58nyrRZu3sRAjHZTJhQ/rua.jpg)

In the work, whose title speaks of “community alternatives for public security without armed confrontation”, she cites as examples of these small actions that have had a positive impact on the place, the creation of Praça da Paz and Memória da Maré, according to data from the De Olho na Maré project.

Rua Evanildo Alves was the theme of the work of another Insper graduate with the support of the Manu Institute. Geographer graduated from UFRJ, Rian de Queiroz, 29, was born and raised in Parque Maré and chose the famous road as the theme of his study: “Between the banks, a center: transformation of the Divisa, in all the favelas of Maré – Phase 1: socio-environmental requalification”. The boundary, as we have already seen, is how the street is treated by residents.

/i.s3.glbimg.com/v1/AUTH_da025474c0c44edd99332dddb09cabe8/internal_photos/bs/2025/n/i/WWh9akQ7qWBid94Xm7lg/foto.jpg)

Rian proposed a socio-environmental requalification that includes recycling, training and integration with existing public policies. The central point of the work is the accumulation of waste in the neighborhood, one of the symptoms of the “problem of marginalization of the streets”, as he writes.

— Waste is the visible mark, but the root lies in socio-economic inequalities. There are people who need to survive on this waste, so large landfills end up appearing there, in the open. The aim of the work is to achieve socio-environmental requalification by integrating recycling, by training these people in an integrated manner with the public policies already existing in the municipality to create a way of fairly remunerating these people — explains Rian.

A graduate of the class of 2024 of the course, Rian explains his choice of street:

— When we choose to work on Divisa, we choose the most complex area to show that if it worked there, it will work in other regions too. Social urban planning talks a lot about this symbolism. The intervention must certainly qualify the territory, but it must also convey a message: transforming a reality considered impossible shows that other transformations are also possible.

Crossing the city from the northern zone to the southern zone, professor of history at the Uerj and doctor of sociology from the same university Franco da Costa Nascimento, 35, has just completed his postgraduate degree in social urban planning. Son and grandson of the inhabitants of Cruzada São Sebastião, in Leblon, Franco of course examined all the buildings designed 70 years ago by Dom Hélder Câmara to construct his final work. The title is short and significant: “The Crusade directly in the photo”.

Franco compared the indicators produced by the IBGE on Leblon with his own surveys carried out during Cruzada, which revealed deep contrasts, notably in the racial profile. It shows, for example, that census data – which analyzes the neighborhood’s 37,709 residents, including Cruzada – reveals that Leblon’s population is made up of 85.8% white, 4% black and 9.9% mixed race, among others. In the Cruzada itself, according to the researcher’s survey, there are 73.3% black, 20.9% mixed race and 4.7% white, among others.

Franco describes Cruzada – where he continues to live – as a unique urban experience in the country, born from the proposal to integrate different social groups in a high-level territory, but which ended up being abandoned by the public authorities. He believes that social urban planning opens the way to the recovery of this original vocation, combining diagnosis, participation and coordination between residents.

— My project begins as a diagnosis, but it does not stop there. The idea is that it evolves towards concrete, even physical, transformations, those that the community itself has identified as necessary. When I opened the “menu” of possibilities, the residents brought very objective proposals: solar energy, community garden, elevators, gardens, selective collection. It’s not abstract. They know exactly what they want to improve the image and daily life of the Crusade, he said.

When asked about something he learned during the course, Franco speaks in dialogue:

— Brazil is too complex a country for ready-made solutions. What I learned in social urban planning is that you have to listen to the resident, without listening to those who live in the neighborhood, it is not possible. There is no point in coming up with ready-made formulas.

The Manu Institute brings together 15 of the most successful offices in the country’s high-end architecture market, whose clients devote 1% of the value of their works to enable the granting of scholarships. Between 2022 and 2025, almost 2.6 million reais have been invested in the program.

— It is more than obvious that traditional agents will not be able to fight against social inequalities and their consequences such as urban violence and environmental racism. It is urgent that the genesis of urban thinking and the understanding of its power as a vector of transformation flourish within communities. Our institute was born from this concern, with the aim of training leaders with the necessary tools to transform the reality of the territories where they live — explains the architect and urban planner Miguel Pinto Guimarães, president of the Manu Institute.