“In times of political excitement, anyone can gather 200,000 people from one day to the next.”

Félix Luna, “The 45”.

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.

What probably caused the greatest astonishment in the last quarter of the 19th century was the urban explosion and its impact on the entire interaction processes. Crowds concentrated in confined spaces, consumption explosions, overcrowded housing, overcrowded public transport and accelerated migrations simultaneously presented governments and their attempts to shape and shape the same social processes with a new set of problems to deal with.

Among all the possible options for reflection, one became more complex in relation to the fact that the individual, conceived in the Western tradition as a rational being and reasoning so only a short time before all these problems, seemed to lose himself as a “self” in the social group, moving in this new and chaotic context as something less than an individual, losing himself in a collective urge that overwhelmed him and led to behaviors and ideas that were a product of his environment rather than a reflexive course. lonely Despite this recent history, the uncomfortable and strange question is still asked about what “people would think” (thinking as an individual and private act), and that there is always someone to go out and explain it on TV, assuming that person’s opinion is also the result of some follow-up.

The obsession with collective response is typical of this context, introduced in the 19th century. The question of the voter as the key to the seat of government or the opposition, the preferences for brands or products that enable the existence or non-existence of a company, or clothing fashions that massively differentiate the acceptable from the unacceptable are just examples of the fact that society is far from being thought of as the result of individual reflection and calculation. Even the calls on social networks to find oneself, through accounts with many followers, are a massive phenomenon, repeated in seemingly personal search exercises, so successful and with so many reproductions that they can only be evaluated or described as a collective fashion. They would all be “individuals” but under the same mechanism. Social networks are also heirs to the massization that has begun in this already marked period, only they react more quickly to success or failure.

In too many cases, political analysis tends to forget this process of social production, replacing the search for common mechanisms that explain general patterns of behavior with rumors or whispers about what is said between people in a meeting. In this way, for example, the fate of the Milei government would not be the result of general patterns of economic performance or already proven relationships between the socio-economic level and the vote, but of how Karina Milei would fight with Santiago Caputo. In this way, all of society’s complexity would be reduced to personal tensions, so that everyone who knew them would be tasked with recounting them at a meeting of businessmen who cared more about these revelations than about the complex features of the society in which they were trying to conduct their business.

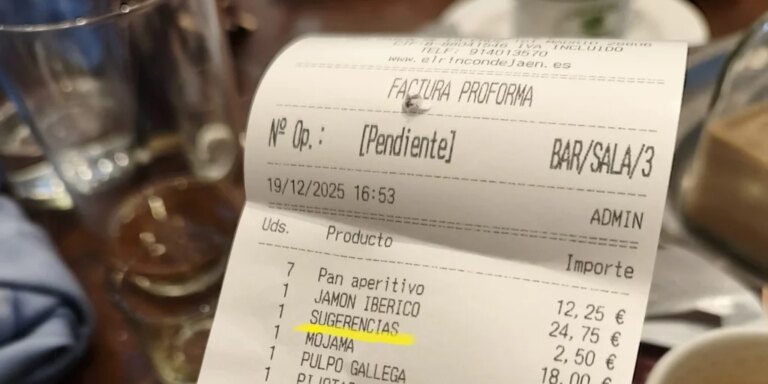

The story’s revelations provide attractive evidence that they are merely anecdotes of a much broader process. Lennon sang to his son: “Life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans,” suggesting the axis of what he is saying is the distance that exists between supposed individual planning and what society produces beyond the intentions of each individual. Towards October 17, 1945, Félix Luna remarkably describes meetings and protagonists, from Perón and Farrell to Amadeo Sabattini and General Ávalos or Alfredo Palacios, to make clear that none of the meetings or planning described there could have explained or foreseen the insurmountable popular demonstration. From what seemed a doomed fate for Perón, he became the most successful and massive political force, and Félix Luna calls the chapter he narrates “The Hurricane of History,” recognizing something fueled by his own energy.

For Milei, this year could be described as his own hurricane in history. He had already starred in the film that brought him to the presidency, but this year in 2025, after September in Buenos Aires province, seemed to be the moment of his end. The private behaviors of political actors followed each other accordingly, and therefore the one who knew best how to obtain the rumors of a fate already observable to all would know the future. But the results once again highlighted the distance that exists between collective behavior and individual planning. Modernity, which symbolically begins with the French Revolution and many others, is characterized by precisely this: unpredictability and improbability.

The exaggerated positioning of the individual in his influence also exaggerates the importance of the idea of change. Communication consultants or other similar types always repeat that they “live in a world that is constantly changing” and that they therefore have the solution and the opportunity to invite their clients to be protagonists in this pandemonium of changes. But what is forgotten above all is continuity, and that seems to be of little interest to people today. The supposed experts of the Milei vote report a change based on what they hear from people, without paying attention to whether the same people voted for Macri ten years ago with different arguments. It is examined in search of the object of change, and only that, because reality would only be a course of changes.

Concerns stemming from sociology went hand in hand with concerns about the massiveness of these cities and conceptual obsessions that provided continuities rather than ruptures. The original Argentine sociological versions were precisely concerned with massification and the loss of individuality, as can be seen in José Ingenieros or Ramos Mejía. Symbolic interactionism recognized the efforts of people to identify themselves in interaction processes in which they could only draw on common social criteria to drive them, or the importance of morality in Durkheim and culture in Parsons and even ideology in Marxism are examples of sociological concerns that left space for reflection on a time evident not only in mutation but also in surveillance. The first election theories that can be read up to August Campbell in the 1960s speak of continuity rather than ruptures, but none of this seems relevant to today’s explainers.

Courses and conferences, lectures of all kinds with speakers experienced in substantiating the meaning of the feature of contemporary fraud, will continually surprise the masses, in a social mechanism that will continue to exist beneath the dominant semantic surface. If what they say never happens, there is always a mediocre solution, an emergency solution, because as they say, everything can change. What they fail to see, the dark and unobservable place of this story, is that they are the ones who represent a continuity in an exercise in description that says nothing about its subject but too much about itself.

*Sociologist.