Argentine history has a habit of speaking through cold statues: heroes who were flammable men, wars remembered as dates, flags hung in a classroom.

But when literature gets into the middle, things change: the story leaves the bronze and begins to seem like dinner after dinner, a dressing room, an oral argument told with the pulse of a novel.

There, in the area where imagination does not reveal but illuminates, books appear that teach us that the past is not a museum but a controversial literary genre. Among many history books, we comment here on some about Felipe Pigna, Eduardo Sacheri and María Sáenz Quesada.

FELIPE PIGNA AND HIS WORK

The most visible phenomenon of this operation is the cycle “The Myths of Argentine History – Volume 1”, which Felipe Pigna opened ten years before the discourses on memory and failure went viral as national common sense.

The project, later expanded to include additional volumes, is based on popular prose: short chapters, front row narration, friendly, ironic tone, moral when necessary and revisionist by definition. Pigna conducts dialogues and polemicizes, above all, with the liberal textbook tradition that dominated the 20th century. He doesn’t want invisible processes: he wants names, faces, motivations, contradictions. And he succeeds every time he describes the intimate sufferings of San Martín or the developmental impulses of Belgrano. But it also stumbles every time the structure of the story inevitably falls back on biographism as the driving force: the people, the classes, the economy appear as background and not as the central plot.

It’s not a failure of style, it’s a genre choice: Pigna tells the story as if he were putting together an extended episode of “Something They Will Have Done,” the TV series that, along with Pergolini, made him a household name.

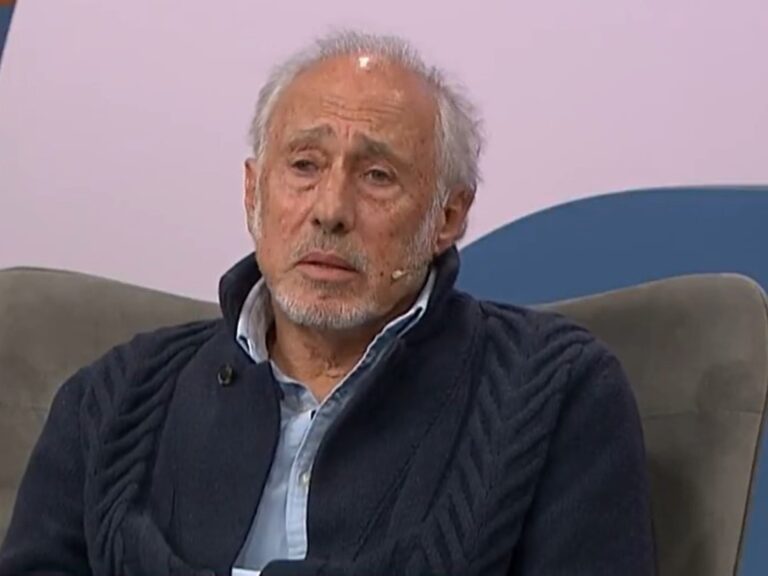

Eduardo Sacheri, historian and author of novels such as “The Question in Their Eyes”, “Too Far” and “How Much I Loved You” / Web

This is where its effectiveness lies: fluidity, speed, conversation. The book became a historical bestseller because it was read as a choral novel about characters rather than a treatise about trials. Twenty years after its publication, its merit lies not in its theoretical depth but in the gravity of the question it raises: Who were we when we weren’t looking? It is literature because it transforms an archive into an episode, a hero into a conversation partner, and a date into a historical milestone.

The synergy and commonality of these three works lies in the way they are told: from the story

SACHERI ALSO WRITES HISTORY

Eduardo Sacheri, who came from fiction to history, made a similar move but with different means.

His book “The Days of the Revolution” is the moment in which he hangs up his novel smock to put on something else: the professor’s overalls, sewn with the narrative patience that he already brought with him from “The Secret in Her Eyes” (film adaptation of “The Question in Her Eyes”). If in Pigna history is a conversation, in Sacheri it is a master class, told as a series of chapters with a novelistic rhythm.

María Sáenz Quesada, author of “The First President” / Web

The author tells of the collapse of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata as a building creaking between wars and projects that don’t quite fit together. Unlike Pigna, his focus is on the archeology of the process: the revolution as an institutional earthquake that produces a country not through spontaneous generation but through the accumulation of cracks, mistakes, courage, coincidences and accidental politics. Sacheri describes historical actors as parts of a taut spine: Dorrego, Rosas, Güemes, Urquiza are important not because they are monuments, but because they embody collapses and new beginnings.

And when he explains the violence, he does so from the materiality of the scene, almost as if he were describing a football game: the blood, the fear, the houses shot up by La Mazorca as a literary parapolice organization in the form of a repressive apparatus.

For Sacheri, then, history is a tragedy on the basis of: understanding before judgment, understanding brutality as context and not as morality. The Days of the Revolution is not just a history book: it is a book full of narrative tensions in which Argentina becomes a random plot.

THE IMPRINT OF MARÍA SÁENZ QUESADA

Quesada practices history from a different perspective, with encyclopedic ambition and a chronicler’s sensitivity. “Argentina. History of the country and its people” is the book that presents the complete temporal map: from the travels of Díaz de Solís, the colonial miscegenation between crown, church and creolism, to the debacle of 2001 and the Kirchner cycle as a chronicle without sufficient distance to become historiography.

Sacheri’s book offers narrative tensions using Argentina as an argument

In this way, Quesada works with the past as an archivist of narratives: chapters that admit their independence but form a long-running river when read one after the other.

This draft is also a choice of literature: 74 historical non-fiction stories that enter into dialogue with one another through contiguity, with a register of names as a paratext in order not to get lost in the density of a developing country. Quesada is literature because it processes the pulse of biographical details and private life as a historical setting: letters, memoirs, travel stories as lived experience, almost like a Uhartian exercise in affective observation, strictly dated.

His difference from Pigna and Sacheri is the scaffolding method: not just names, not just processes, but a monumental device that does not abandon the horizontal line of time. It is the literary equivalent of a country logbook: the political data is the backbone, but around it lie intimate scenes, sensibilities and epochal contradictions. Quesada does not sanctify, he commands; don’t judge, describe; and when he explains the country’s structural difficulties in complying with the law—”I comply, but I don’t comply,” declared Hispanic officials—he does so with a narrative clarity that makes the past a cultural tool rather than a sentence.