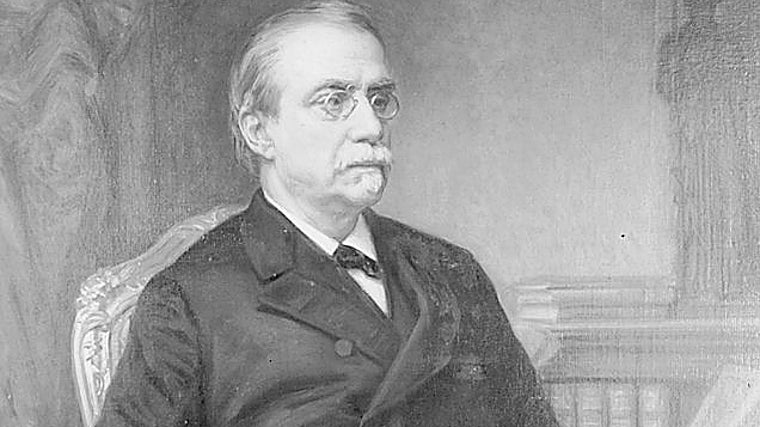

On August 8, 1897, in the town of Santa Águeda (Guipúzcoa), the Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo assassinated the President of the Council of Ministers, Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, with three bullets. The assassination, carried out with precision and political conviction, caused shock … immediate in Spanish politics: General Valeriano Weyler was relieved of his duties as Captain General of Cuba by Práxedes Mateo-Sagasta, his successor as head of government, thus truncating his plans for a quick victory in the war of independence taking place on the island.

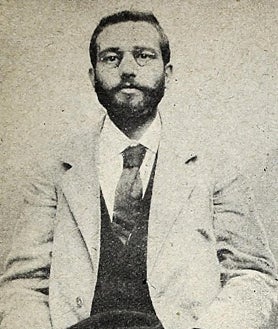

The execution of Angiolillo, by means of a vile garrote in the Vergara prison, closed a bloody chapter in Spanish political history and became the symbol of a method of execution which will deeply mark the collective memory. Born in Foggia (Italy) in 1871, a typographer by trade, the assassin was linked to anarchism from a very young age. After participating in demonstrations against the government of Francesco Crispi, he fled to Marseille. In the mid-1890s, he traveled to Barcelona and settled in the Francia Chica neighborhood of Poble Sec. There he collaborated with the magazine “Ciencia Social” and was monitored by the police. His activity in Barcelona directly linked him to the Catalan anarchist milieu and the repression of Montjuïc.

With all this experience acquired in Barcelona, he moved to London, where he came into contact with international revolutionary circles and established himself as an anarchist activist. In the British capital, he interacted with many exiles from different countries. But his journey does not end there. At the end of July 1897, he moved again, this time to Paris, where he met Ramón Emeterio Betances, a Puerto Rican activist who worked as a representative of Caribbean independence activists in Europe.

This doctor and revolutionary, considered the father of the Puerto Rican freedom movement, was the one who dissuaded him from attacking young Alfonso. This, however, did not make him abandon the path of violence and he directed his objective towards none other than Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the president of the Council of Ministers, who is the same, the president of the government in these last years of the 19th century.

To implement his project, he went to Madrid and contacted José Nakens, the republican journalist whose professional life was linked to the satirical weekly “El Motín” and who, years later, would receive financial assistance from such important figures as Gregorio Marañón, Ramón Pérez de Ayala and Luis Araquistáin. Angiolillo, under the false name of Emilio Rinaldini, obtained the money which allowed him to travel to the Basque Country and stay at the thermal baths of Santa Águeda, where Cánovas del Castillo usually went. Nakens later admitted that the killer had hinted at his goal, but did not take it seriously.

The assassination

On the afternoon of August 8, 1897, the president was resting in the spa garden with his wife. Angiolillo approached, posing as a journalist, and shot him three times: two bullets in the body and one in the head. Cánovas del Castillo fell mortally wounded while his wife called for help. The murderer didn’t even try to escape. He was immediately arrested and confessed to the crime, which he justified as revenge for what had happened in Montjuïc a month before: a terrorist attack on the Corpus Christi procession that left 12 people dead and the subsequent government crackdown in which some four hundred anarchist activists were arrested.

The press

“The bullet entered through the chest and exited through the back. “The third shot was fired while Mr. Cánovas was on the ground.”

‘Golden Ant’ magazine reported it in surprising detail: “The first shot was followed by two more, which also hit the target. Following the first bullet, the president stood up and fell three meters. When Mr. Cánovas stood up, the assassin fired another shot. The bullet entered through the chest and exited through the back. The third shot was fired by the assassin while Mr. Cánovas was on the ground. “This last bullet entered from the back.” And the newspaper “La Época” added: “The assassin, who was undoubtedly spying on him, approached and, leaning on the door to aim better, shot him at point blank range.”

With the death of the President of the Government, the Restoration lost its architect and a crack opened in the political system at the end of the century. Angiolillo, for his part, was taken to Vergara prison and subjected to a speedy trial. It only lasted a few hours. The courtroom was packed when the accused entered under escort, straight and composed. He heard the accusations without denying anything, he firmly confessed to them, saying he did it out of revenge. His remarks read more like a political manifesto than a defense of the assassination. The court found him guilty and handed down the maximum sentence: death by garrote. The sentence was carried out on August 20 of the same year, just 12 days after the crime.

The executioner

The person responsible for the execution was Gregorio Mayoral Sendino de Burgos, renowned for his skill and discretion, who would soon after be known as “the grandfather” for his long history of prisoners whom he killed throughout his career: a total of 47, including Cánovas’s assassin. At eleven o’clock in the morning, he climbed the steps of the improvised scaffolding in the prison courtyard. Angiolillo waited there, at 26 years old, pale but firm. The executioner adjusted the metal collar and activated the mechanism. Then he covered the executed man’s face with a black cloth and calmly went downstairs. This act, executed with cold efficiency, symbolized the decline of an era.

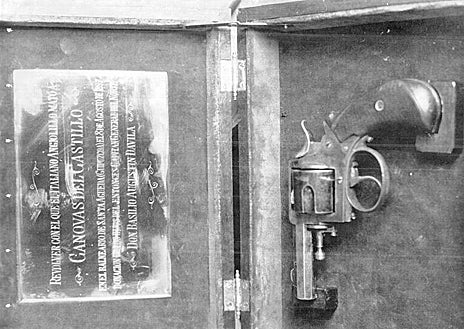

Shortly before dying, Angiolillo shouted “germinal!” », evoking the revolutionary month of the French republican calendar and the rebirth of the workers’ struggle. His gesture, calm and defiant, was recorded as a symbol of the political violence of the end of the century. This is partly due to the fact that his execution was photographed and reproduced in the press, an exceptional event in Spanish criminal history. The images show the improvised scaffold, the wooden chair, the mechanism of the club and the serene face of the condemned man. To visit these scenes is to confront an echo of the political violence that spanned the Restoration.

However, this was the last vile garrote execution carried out in public, although the instrument remained in force until a year before the Franco dictatorship. Concretely, the last two prisoners to suffer, on March 2, 1974, were the also anarchist Salvador Puig Antich, convicted of the death of a police officer during a shooting during an irregular trial which made him a symbol of Franco’s repression; and Georg Michael Welzel, a German citizen known as “Heinz Chez,” accused of murdering a civil guard in Tarragona. Their simultaneous execution was interpreted as an attempt to depoliticize the case of the former. According to ABC on the day of his execution: “No communication was received from the outside interested in his body.”

With them, the cycle of institutional violence was closed. Although the death penalty was suspended in practice in 1978, the garrote did not disappear from the Penal Code until 1983, when Spain definitively abolished this method of execution.

Pencil portrait of Cánovas del Castillo, made in 1897

Angiolillo’s footprints

Today it is possible to visit some scenes related to the last days of the famous anarchist Vergara. Although there is no tour per se, you can visit the cell where he stayed “in a chapel”, located in the old courthouse of Vergara, now transformed into a gaztetxe. Continue to the place of execution, the same one where the infamous club was located. The space is preserved in an exterior patio of the same building, protected by a high fence. A plaque in Basque was placed there to commemorate the event. And you can also go to the local cemetery, where Angiolillo’s remains were buried in a mass grave. Every August 20, a floral offering appears outside its wall in homage to the anarchist and to remind us that memory does not die: that crime and its punishment continue to dialogue with the present.

The crime of Santa Águeda and the execution of Vergara condense the clash between power and revolutionary movements in Spain at the end of the 19th century. The figure of Angiolillo embodies the paradox of a man who chose violence as a response to violence. The revolver with which he committed the crime is in fact currently on display at the Alava Armory Museum. His serene gesture, his last word – “germinal!” – and the mechanical ritual of the executioner compose a story that transcends the anecdote: the end of a man and the beginning of a collective memory marked by politics and blood, where this instrument of iron and wood became the symbol of an era where justice was confused with the spectacle of punishment.