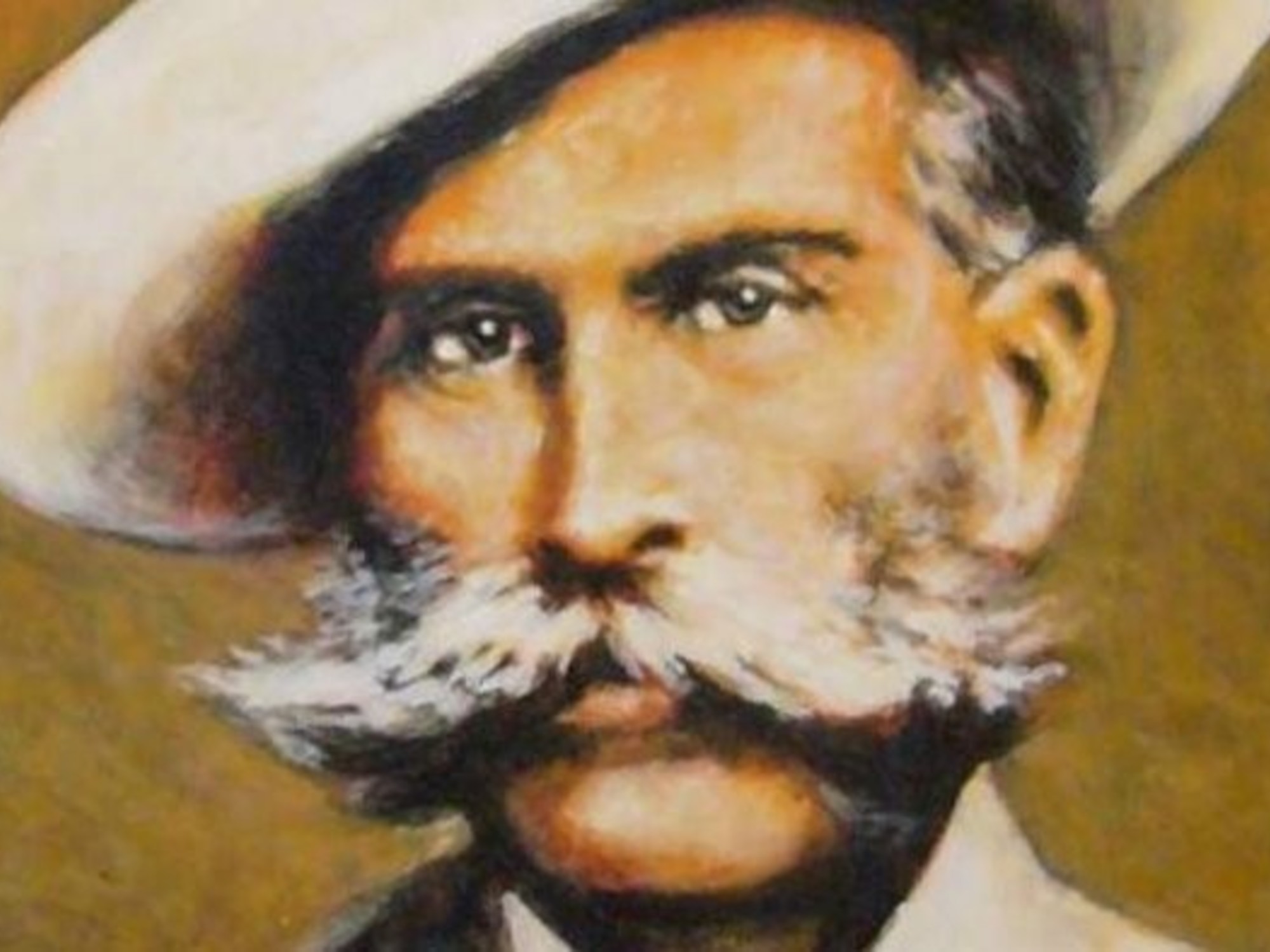

On the dusty shores of the Guanacache Lagoons, between Mendoza and San Juan, a man who would become a myth was born around 1830. His name was José de los Santos Guayama, the Huarpe Gaucho He challenged power and secured a place in the people’s memory.

He spent his childhood in the Huarpe communities that survived the drought of Cuyo. There he learned to ride, how to handle the facón and, above all, how to play the guitar. Music would always be part of his identity: it was said that Guayama could move from serenade to fighting with the same ease, as if singing and fighting were two sides of the same rebellion.

As the Confederacy and Buenos Aires argued over the fate of the country, Guayama joined the Cuyan Montonerosthose popular armies that followed leaders like El Chacho Peñaloza and Felipe Varela.

He was not a soldier from an academy, but a man of the people who knew every corner of the lagoons and every path of the mountain. His force consisted of poor gauchos, Huarpe natives and farmers who saw in him a leader capable of confronting injustice.

The official story called him a bandit. But for his people he was a lagoon leader, a Defender of the autonomy and dignity of the forgotten. His rebellion became a threat to the provincial authorities, who persecuted him for years.

And yet Guayama seemed indestructible: he survived ambushes, escaped execution, and resurfaced when everyone left him for dead. That’s why people called him “the man who died nine times.”

His figure became legendary. He was described as a tall, bearded man with intense eyes who could spend the night singing songs and lead an attack against official forces at dawn. This mixture of musician and warrior made him a unique character, half real, half myth.

In 1879 there was finally a streak of bad luck. Santos Guayama was captured in San Juan. The strength needed to teach a lesson and erase from popular memory the gaucho who had challenged authority. They shot him, ending a life marked by rebellion.

But Death did not achieve what they sought: Instead of disappearing, Guayama became a legend.

He is still remembered in the Lagunas de Guanacache. His name circulates in oral stories, in songs and in the memory of the descendants of the huarpes and gauchos who followed him.

In short, Santos Guayama is a symbol of this Argentina that arose between shootings and oblivion, but also between guitars, rebellion and resistance.

The Guanacache oral tradition states that Guayama had a special relationship with the saint. Some testimonies collected by researchers tell of a conversation with the priest Brochero in long conversations about justice and faith. For his followers, this closeness to religion reinforced the idea that their struggle was not one of banditry but of a righteous, almost spiritual cause.

The anthropologist Diego Escolar reconstructed how Guayama and his Montoneros They founded what residents called “the lost republic.” in the Guanacache Lagoons. There they organized themselves as an autonomous community between 1860 and 1870 with practices adopted from colonial indigenous traditions.

The testimonies speak of an area into which state power rarely entered and where Guayama was recognized as a legitimate chief. This fueled the legend of a leader who not only resisted but also ruled.

Another story tells that when they left him for dead, Guayama emerged on his horse, covered in dustas if it came from the earth itself. This gave rise to the popular phrase: “Guayam doesn’t die, it hides in the lagoons.”