Today, this situation would be difficult to imagine: a man who falls in love with a young stranger he meets at the tram station. To make matters worse, she’s a novice. He, Antonio, belongs to the gray middle class: forty years old, a decent job in an office, a girlfriend he sees in the afternoon, flirtations without consequence with a colleague. A guy who is neither brilliant nor attractive, who settles down – that’s the key: conformism – with an uneventful existence, which nevertheless plunges him into chronic dissatisfaction. “I am a coward,” he said to himself. Cowardly for not daring to change.

The emergence of the novice in his daily life gives him an impulse, at first more idyllic than real: thinking about her, spending time imagining what she is like, what could happen, what he would say to her, occupies part of his hours, of his thoughts. Today, the Antonios (and Antonias) of real life would not fall in love at the tram stop because their eyes would be fixed on their cell phones, but they could realize this idealization of the stranger, precisely, in someone they observe through the window, through the filters of a shared image. The circumstances change, but not the essence.

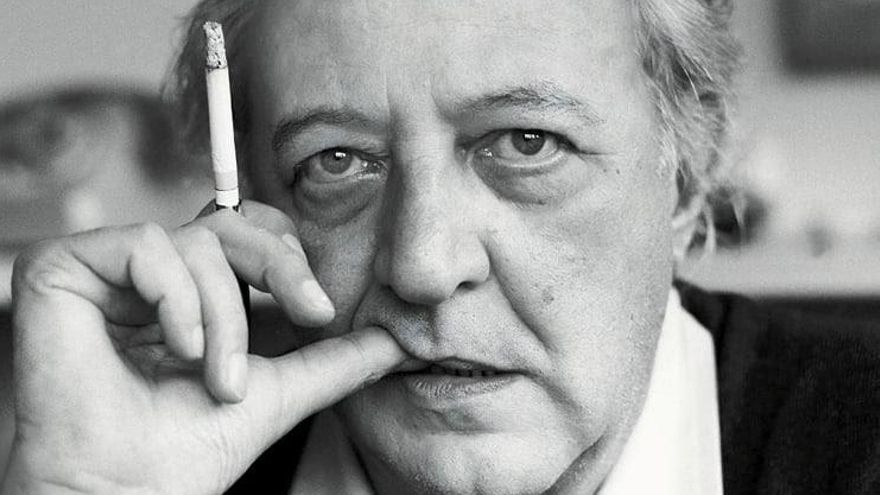

So any man (1959; Gatopardo, 2024, trans. Mariana Ribot), a novel by Giovanni Arpino (Pola, Istria, 1927-Turin, 1987) unpublished in Spanish, still has, more than sixty years later, much to express about human nature and its search, so often unsuccessful or poorly channeled, for something similar to happiness, to the spark that ignites the engine of being. alive. Written in the form of a diary, with this writing stripped of artifice which is only achieved with great skill, the narrator’s adventures are revealed to the reader at the same time as he experiences them, in less than a month, from December to January.

It is no coincidence that history evolves from one year to the next: culture colors this change as the opportunity to make a personal transformation. Antonio Muñoz Molina, author of the prologue, links the protagonist to Pessoa’s Bernardo Soares, Melville’s Bartleby, Joyce’s Leopold Bloom or Kafka’s characters, men “without heroism or tragedy (…), those who seem to aspire to invisibility”. With words they express the desire for something different, but with actions, which ultimately define who we are, they remain bound to the chains of their choice.

Antonio deliberately chose not to engage. He lacks professional aspirations, he postpones marriage, and with it the possibility of having children, his flirtation with his partner never crosses certain limits. He lives alone, takes the same route every day, sees the same people. He survives in this unpleasant, self-imposed routine, unable to fully experience anything. He renounced risk, responsibilities, and with them the possibility of surprise, of joy. Like a contemporary Peter Pan, only Antonio no longer finds this frozen adolescence amusing.

The turning point turned into a whirlwind of emotions

Crossing the path of the nun (that is to say the noveltywith the possibility of something new) is the turning point. It could have been another individual, but religious identity adds a specific nuance to the equation – curiosity for the veiled, adrenaline for the forbidden. At first glance, this is a safe rambling, since it is limited to the wandering of the protagonist’s mind, without practical consequences. However, it turns out that this game is shared by her, who responds to looks and gestures. Eventually, they finally talk, a step that triggers a whirlwind of emotions in Antonio.

The mystique of the relationship with foreigners, today amplified by the effect of networks, hides numerous conflicts: the unknown of who the other really is, how much they lie, how much they hide; and, at the same time, which side of ourselves we choose to show and which we must silence. This opportunity to start fresh with someone who hasn’t experienced our previous versions—that is, our mediocrity, our mistakes, our environment—is tempting, a Faustian pact that attempts to maintain a state of perpetual firstness.

As in cybernetic relationships, Antonio and the novice establish an exchange based on the verb, that is to say on what they say to each other – with this long central dialogue which is almost a monologue – on words (mental constructions) in advance of action, of reality. The novel shows how a single conversation, when fueled by a certain dose of fantasy, can completely change the life of someone and those around them. The nun’s response is surprising and the protagonist, until then so clinging to what belongs to him, loses control of events.

From fantasy to reality

Opening yourself to change brings you peaks of intensity; Now, to what extent can you leave it all behind? Or perhaps it would be more relevant to ask to what extent desirable transform the fantasy, a fantasy without any basis, into reality. Climbing a staircase allows you to discover new views, but there is a risk of tripping, falling before reaching the top, or arriving bruised. In life, it’s always like that, living – and not only exist– involves taking risks.

Giovanni Arpino, author of around twenty novels and short stories, tells the story of an existential search, of the crossing of two loners in the spectral Turin of the fifties, a city mirroring the lethargy of the protagonist. A short and incisive book which, contrary to romantic clichés, invites us to wonder if two newfound solitudes cancel each other out or if, on the contrary, they amplify each other. Beneath its apparent simplicity, due to the refined writing and the linearity of the story, the author, who throughout his career has received prizes such as the Strega or the Campiello, underlines in any man certain contradictions inherent to the human being who, even today, is clairvoyant in his diagnosis of what happens when we dare to break “this damn prudence which makes us stumble at every step”.