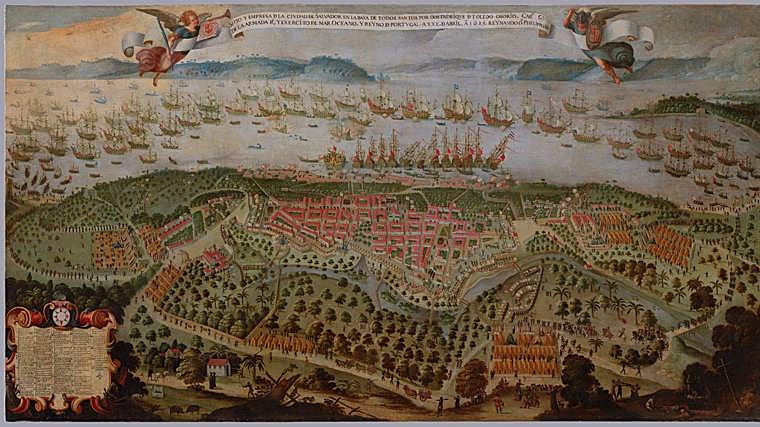

Four centuries have passed since the Hispanic monarchy demonstrated to the entire Old Continent its power in the Americas with the reconquest of the Dutch from Salvador of Bahia. Decades and decades during which all of Europe was convinced that … Such a military feat, crossing the Atlantic with an army of unprecedented dimensions and besieging a Brazilian city, had been carried out by the Count-Duke of Olivares, whom you know well because of his career as a supporter of Philip IV. But the past hides surprises, and this story came to light in 2020, when a gigantic painting lost in time revealed that the glory actually belonged to another soldier: Fadrique of Toledo OsorioI Marquis of Villanueva de Valdueza. A genius who fell into disgrace for his clashes with the monarch’s lieutenant.

“This discovery constitutes a historic milestone. 17th century paintings are not discovered every day and, above all, you don’t discover paintings with so many stories inside,” he explains to ABC. Antonio Pérez Molero. The director is lucky, because it has just been released ‘Bahía 1625, story on canvas‘, a documentary in which he recounts the long journey from the discovery of the oil painting by David García Hernán (professor of modern history at the Carlos III University of Madrid) in the house of the current Marquis of Valdueza, to its restoration and analysis in search of past truth; in this case, the restoration of Don Fadrique’s honor an eternity later. Because yes, sometimes the pages of the calendar have to be turned so that reality comes to light and justice materializes.

Molero looks proud. Logical since it reveals the result of a year of filming and editing. However, he admits that his work is one of many steps that exist in this project. “I am very grateful to Professor García Hernán, it was he who knew how to see the importance of painting and the one who launched the entire research team on the work, which found its maximum expression in the magnificent exhibition that the Naval Museum of Madrid organized last year”,Annus Mirabilis, the credit of Spainwith the painting as the main piece”, he explains to ABC. And this, without counting the long list of conferences and round tables which have been given all over the world and the publication of a choral essay on the theme: “History on canvas. Site and company of Salvador de Bahía, 1625” (Flint).

The story deserved a documentary, and this one, based on the animation of the canvas on the big screen, came from the hand of Molero. “We started in March 2024, thanks undoubtedly to the Naval Museum, who from the start supported the images and made this possible. This was followed by another year and a half of work between the preliminary documentation, writing the script, locations and filming,” he explains to ABC. The latter, he confirms, took them to Lisbon, Amsterdam, Cádiz, Salamanca, Salvador de Bahía and Madrid.

The director says that the challenges were numerous, but the satisfactions were greater. “The most difficult thing was the short time we had, knowing that we had to release it in 2025, coinciding with the 400th anniversary of the events. It was also difficult to obtain sufficient financing to do it with the standards that we set for ourselves from the beginning, but, otherwise, it has been a great adventure”, he says. Although what pleases him most is to have done justice to a character forgotten under the carpet of history. “If he had not had the confrontation with Olivares, Fadrique would surely be as well known today as Ambrosio Spínola or other soldiers of the time”, he concludes.

Find and company

The start of this project is dated: 2020. It was then that Alonso Álvarez de Toledo y Urquijo, the 12th Marquis of Valdueza, showed the painting to García Hernán. From there, the deployment was orchestrated. “As a historian, I saw from the beginning that the painting was an open history book. A testimony of the battle which was not static, but rather told in phases”, explained the professor to ABC less than a year ago. And from there, to a colossal exhibition which began with the restoration of the oil painting, 3 meters wide by 1.62 high, by the Naval Museum and which continued with a long list of evidence in search of its authorship and its secrets.

What is clear is the history of the city’s conquest. According to García Hernán, the Dutch took Salvador de Bahía from the Crown in May 1624. The blow was painful because the silver trade was controlled from these distant lands, but also because of a possible domino effect. The reputation of the monarchy was at stake. On December 12, the largest fleet to have crossed the Atlantic to date left the peninsula: 52 Spanish-Portuguese ships, 12,566 men and 1,158 cannons. And at the helm, Don Fradrique, veteran of the Battle of Gibraltar and the battles against the Berbers. The group arrived at their destination on March 31, 1625, Easter Monday, and our protagonist landed his men on two nearby beaches.

The original painting, after its restoration

Once on land, he set up three camps with which he besieged the city. It was seen and unseen. On April 30, the capitulations were signed and this pearl once again shined with Catholic brilliance. From there, everyone wanted to seize victory and forge their own history. But the one who won was the count-duke, servant of Philip IV. “The official chronicle was that of Tomás Tamayo de Vargas“Very flattering to Olivares,” García Hernán told this newspaper.

In exchange, the rest of the visions were buried; among them, that of a Don Fadrique separated from the court and that of his personal chronicler. Currently, the team of researchers maintains that the order could have come from his family; They sought to restore their honor. However, they continue to study who the painter they chose was. The findings, they claim, are presented in the essay.

–Most of the documentary is based on the animation of the painting. What difficulties did this pose? How was it made?

The animation of the painting was possible thanks to the entry into the project of Daniel Herrera (Akanko Studios), a Spanish animator based in Tokyo with whom he had already worked on other projects. From the beginning, it seemed an impressive challenge to recount the battle based on a 17th-century painting, and he took on it with enthusiasm. We worked on the animations for six months, practically by hand, animating each sequence “frame” by “frame”, digitally cutting out the hands, legs, head, weapons… of each character and animating them in an almost hand-crafted way, because the AI tools tested were of little use in cleaning up the backgrounds.

“This discovery constitutes a historic milestone. 17th century paintings are not discovered every day and, more importantly, paintings with so many stories inside are not discovered.

Daniel has, in addition to great technique, great sensitivity, which gives the animation sequences a cinematic touch. The truth is that it was pure magic, or alchemy, because I proposed that the action be represented in a sequence based on the scenario, I gave him the text that accompanied it (always taken from testimonies of the time) and he literally brought them to life.

–They recorded in Salvador de Bahía… In your opinion, what memory remains of the Spaniards there?

Today in Salvador you can visit many scenes of what happened in 1625, there are even commemorative plaques, but curiously there is no knowledge of Brazil’s Spanish past, which surprised us, especially because there is extensive knowledge of the Dutch past. For many Bahians, this was the first mention of our shared past, which surprised them greatly. I have the feeling that this oversight must be a side effect of the break between Spain and Portugal that began in 1640. All in all, the documentary was screened in Bahia last week, thanks to the Cervantes Institute and the Flàvia Aubaki Institute in Salvador, and the reception was wonderful. A lady from the audience said they should see it in every school in Bahia so that Bahians know their history.

–What do you think of Don Fadrique? Do you consider him a hero mistreated by History?

Don Fadrique is a very interesting character, as is his last antagonist in the story, the Count-Duke of Olivares, another character who well deserves an in-depth cinematic review, because he has it all: intelligence, ambition, model of state… and ego. I believe that Don Fadrique is also a good example of what our society was like at the time, in which the nobility represented the highest social and moral category. In his final confrontation with the Count-Duke, noble logic and honor weigh equally heavy.