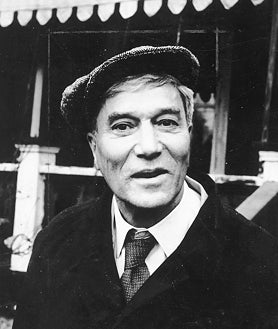

Boris Pasternak was not expected in Stockholm, just as María Corina Machado was expected this Wednesday in Oslo with great anticipation. We do not know where the Venezuelan opponent has taken refuge for more than a year with Nicolas Maduro and … He feared he would not be able to overcome the Chavista obstacles to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in person in the Norwegian capital, but no one doubted his determination. But in 1958, everyone knew that the author of “Doctor Zhivago” would not travel to Sweden because Khrushchev’s Soviet regime had forced him to refuse the Nobel Prize for Literature just days after the prize was awarded to him.

Pasternak’s son told ABC in detail about the blackmail that ultimately broke the Russian writer. This prize, says Evgeny B. Pasternak, “became a scandal. “It poisoned the rest of his life and was, for 30 years, a taboo subject in the USSR.” Although his name had been discussed since the end of World War II, the telegram from the secretary of the Nobel Committee arrived in October 1958. The Swedish Academy had unanimously decided to award him the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his significant achievements both in poetry contemporary lyric than in the field of great Russian poetry. tradition.” Pasternak responded to Anders Österling: “Grateful, happy, proud, confused”. And soon the congratulations and journalists “arrived by the dozen”. “It seems that all the damage and oppression that followed “Doctor Zhivago”, appeals to the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the Writers’ Union were over,” said Pasternak’s son. Nothing more.

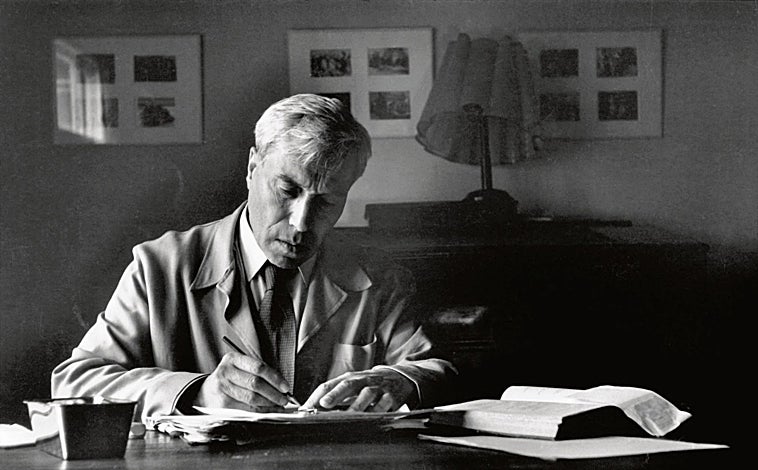

Just days after Life magazine published some photographs of the writer at his “dacha” on the outskirts of Moscow, writing in his office or sitting on a garden bench stroking his dog, the police stationed themselves outside his house to prevent his access and on October 29, a dramatic telegram from Pasternak to the Swedish Academy was made public: “With the greatest gratitude, It is not possible for me to accept the Nobelbecause of the importance that has been attributed to this award in the society to which I belong.

Testimony of Yevgeny Pasternak

According to Evgeny, his father’s “proud and independent” position helped him endure the insults and threats made by the Soviet media during the first week. At a Writers’ Union meeting at which her exclusion from membership was discussed, one participant even shouted: “A bullet to the traitor’s head!”. Pasternak, who was not present, defended himself in a letter: “You can kill me, send me into exile, do whatever you want (…) Remember that, In a few years, I would have to be rehabilitated. “It wouldn’t be the first time they’ve done it.”

His resistance faded, however, on October 29 when he telephoned Olga Ivinskayahis love for the last 14 years of his life. After sending the resignation telegram to the Nobel Committee, he wrote another to the Party Central Committee: “Give Ivinskaya her job; I refused the price”. According to Pasternak’s son, they did not dare to confront her because they had no “justified” reason and instead “attacked Ivinskaya”, who had spent years in Lubyanka prison and political prison camps in Mordovia. “She bitterly accused herself of having persuaded Pasternak to refuse the prize,” writes Yevgeny, although he understood her: “The memory of Stalin’s camps was too vivid; “She was trying to protect him.”

Pasternak’s sacrifice did not improve their situation. He was forced to sign texts written by the party in Pravda, “a torment to his will” which was particularly painful for him. In his poem ‘The Nobel Prize”, the publication of which also caused him problems, he wonders what kind of dirty crime he committed, which made everyone cry in front of the beauty of his country. He died in 1960, only two years later, and after his death Ivinskaya was sent to the camps in Mordovia. It was “the saddest and cruelest thing,” Yevgeny noted on ABC in 2009. He was the same age as his father in 1958.