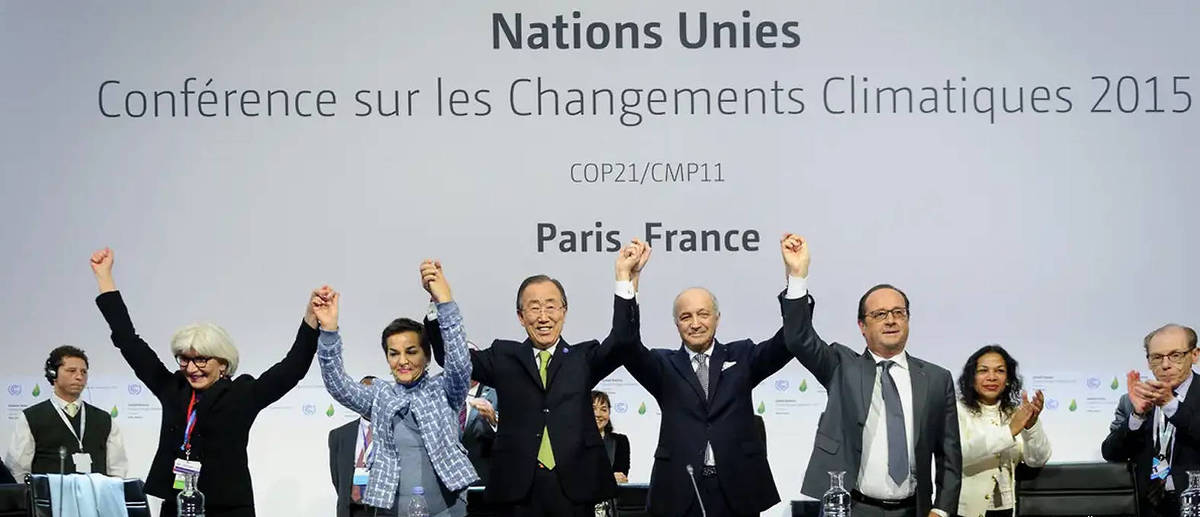

Exactly ten years ago, ending this Friday (12), a marathon of climate negotiations ended in celebration. At the Le Bourget exhibition center, 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement. The landmark document changed the world’s perception of climate change and established parameters for assessing it.

A decade later, thanks to them, it is possible to realize that the situation is not good.

The fruit of the tireless efforts of French diplomacy, COP21 was designed to succeed. All sorts of strategies were used to keep conversations from getting lost. Even a Zulu tradition came into play to force negotiations.

In the final document, unprecedented commitments emerge: countries should “continue their efforts” to keep global warming “well below 2°C” compared to pre-industrial levels, ideally at 1.5°C; Countries would set their own targets to achieve the goal, but it would be mandatory to publish them.

What’s more, the signatories recognized the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and committed to doing so, even in different proportions, because it is the only way out of the problem. “Common but differentiated responsibilities.”

A superficial reading of thermometers and current studies would indicate the failure of the agreement ten years later. Given the current targets announced by countries, called NDCs (nationally determined contributions), the world is on track to reach a temperature 2.3°C to 2.5°C warmer by 2100.

Emissions are increasing and could reach a new record this year, leading scientists and the UN to believe that the planet will not escape “overshoot”, when it will no longer be possible to reach the trajectory towards 1.5°C simply by reducing emissions. Negative emissions, which remove carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, are currently an unachievable task on a global scale.

Bad with Paris, worse without the agreement. The world would be on a 3.9°C trajectory without the series of happy, connected episodes from a decade ago.

Starting with the decision to hold COP21 in Paris a few weeks after the multiple terrorist attacks in the French capital, which left 130 dead and nearly 400 injured on November 13. François Hollande defended the continuation of the event as a means of strengthening the unity of the country. More than 150 heads of state attended the then French president’s opening of the conference.

Bringing leaders to the start of negotiations, which had never happened before, was the first of many strategies launched by the French to move the deal forward. The idea was to avoid what happened in Copenhagen in 2009, when representatives began trading barbs in public, jeopardizing the final stretch of negotiations.

In Le Bourget, a suburb of Paris, the office of the French presidency of COP21 has been strategically installed above the facilities of the UNFCCC, the UN Panel of Experts on Climate. Laurent Fabius led a team of 60 negotiators who even had small rest rooms.

Several dialogue dynamics were implemented. The ultimate forum for negotiation came from South Africa, the “indabas”, a Zulu tradition of bringing together elders to resolve disputes between communities. In the French version, groups formed to seek alternative paths in times of great divergence.

There weren’t a few. On Wednesday of the second week, we had to call on the heads of state. Barack Obama called Xi Jinping and Hollande called countless representatives. According to Peter Betts, climate negotiator for the United Kingdom and the European Union, the United States and China participated in numerous bilateral negotiations during the conference.

“On the one hand, it was clearly good that they were talking. On the other hand, what were they talking about?” Betts writes in a posthumous book published this year in England — the diplomat died in 2023 of a brain tumor.

The first full version of the agreement was published the following day. Unlike many European colleagues, Betts condemned the document, warning that predictions that developed countries would release $100 billion a year were not achievable.

There have been many disputes. One of the most difficult has been the 1.5°C warming limit, determined by science to be a reasonable level to maintain the health of the planet. The need to achieve so-called “net zero,” or net zero emissions, predicted since Eco-92 in Rio, the mother of all climate conferences, was not new.

What came to Paris was the idea of giving a deadline to the objective, 2050, as it ended up being achieved. However, for environmentalists, pursuing net zero in the long term would distract from the even more urgent need to reduce emissions within 10 or 15 years. Current emissions and warming figures show they were right.

Betts says the United States and its allies were opposed to imposing a 1.5°C limit, as were developing countries, which publicly blamed the richest. This demand actually came from the countries most vulnerable to rising sea levels.

The next project proposed by the French sought a juggling and intelligent formulation to deal with the problem. The objective would be to limit the rise in temperature “well below 2°C”, while “efforts continue” to reach 1.5°C.

The only country to oppose the paragraph was Saudi Arabia, which has since become the leading voice of opposition to climate change. The “road map” for the end of fossil fuels proposed by the Brazilian presidency during the last COP, in Belém, was the latest victim of the group of petro-states led by the Saudis.

In Paris, the negotiations finally broke the deadlock. Last Saturday morning, in an almost theatrical manner, Hollande appeared at Le Bourget to celebrate the conclusion of the agreement, the latest version of which had not yet been read by the negotiators.

RELEASE IN FRENCH

A few hours later, the announcement of the signing of the document still had to overcome one last obstacle. US government lawyers realized that the country’s diplomats had left a “must” in the text instead of “should” in a paragraph on the obligations of developed countries.

The argument of the American delegation led by John Kerry was that the present, which denotes an obligation, instead of the future, which expresses conditionality, would not be approved by the country’s Congress. Vulnerable countries and Nicaragua called the move a coup.

The agreement having already been approved, there was no question of revising the text. Another French solution then emerged: it was a typo, attributed to a tired negotiator.

On the tenth anniversary, the celebration is measured. Discussions on the formats of the COPs and the lack of binding nature of the objectives are weighed against the technological and economic race generated by the agreement. If Paris wasn’t enough, it also put the world on a one-way path away from fossil fuels.

Global warming remains far from a solution and extreme events are becoming more and more frequent. The deal, with all its limitations, exposes the biggest suspects.

The ranking of performance in the face of the climate crisis prepared by environmental entities Germanwatch, NewClimate Institute and CAN places Denmark in fourth place. No country has enough performance to reach the top three places.

Brazil occupies 27th position, now threatened by the dismantling of environmental licenses led by Congress. Saudi Arabia, which has not even published its NDC, comes in last place.