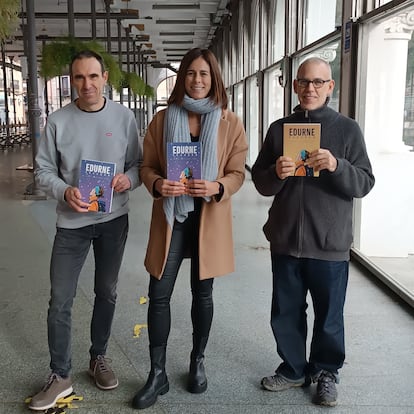

On the other end of the phone, Edurne Basaban introduced herself and offered to meet, have coffee and talk. After all, they were both born in Tolosa, Guipuzcoa, which made things much easier. It happened less than five years ago, and at that time Julen (a figurative name) was spending dark hours without a clear diagnosis for a mysterious illness that had plunged him into the pit of depression, a form of anguish similar to the one Basaban herself had known years before, in the vortex of climbing the 14 eight-thousanders on the planet. They did not know each other, but Jolene agreed to meet, they talked in a relaxed manner and when they said goodbye the illness was still there but qualified by a decision: to fight without the temptation to end everything radically. Today, after Jolene has fully recovered, he still believes that this gesture is what defines Edorn, much more than the title of the first woman to climb the Eighteen Thousand Fourteen summit. The now comic book collects the checkered life of the Basque mountaineer, vignettes and short texts that weave together her delusions, dark episodes, and obstacle-filled road until she became one of the great feminist authorities on mountaineering.

The comedian Edorn Basaban (Sua and mendifilm editions) With text by Ramon Olasagaste and illustrations by César Laguno, Felipe Navarro, and Pedro Villarejo, this book breaks from the mold of classic mountain stories to address issues such as masculinity, the role of women in the history of mountaineering, their loneliness in a man’s world, and the suffering that, in Edurne’s case, came to outweigh the joy of the summits.

Thirty years ago, when she was climbing or walking in the Txendoki area, she… Basque MatterhornShe did so surrounded by men as part of the small percentage of women who went out into the mountains. Today, in Txendoki itself, there are abundant groups of women, and women’s groups as well, most of them motivated by the example of Pasapan and the change in mentality that occurred during the epidemic. It has been a long way, but today the women of this country have strong references, a need that Edurni once covered by visiting women like Billie Janoza, or revisiting the legacy of the lost mountaineer Miriam García Pascual.

To create the text of the storyboard, Ramon Olasagasti spent hours chatting with the protagonist, who did not hold back from anything, an honesty reflected in the work that surprises the unsuspecting reader. First of all, her first expeditions to the Himalayas were marked by her affair with the Italian Silvio Mondinelli, a married man with two children from whom she never separated: “What would have happened if Edurne had been the married woman with a family who enjoyed an extramarital affair on expeditions?” Olasagasti asks. They were going to crucify her, surely the same people who had treated Billy Janoza so cruelly when she started traveling to the big mountains despite being a mother. In the comic, Edurne is never depicted as a great climber, nor as an exceptional woman, even if she became the first to set foot on the 14 highest mountains on the planet: it is this demystification that gives additional value to her reading. The meaning of Mountaineering has more to do with the interior of its protagonists than with what they display on their social networks.

Pasapan climbed Mount Everest in 2001, his first major summit, and in 2004, on K 2, he nearly lost his life. She was exhausted during the descent, but Juan Vallejo guided her to safety at high altitude and saved her life. But Edorn’s fragility had nothing to do with her physical performance, but rather with self-imposed pressures exerted from the outside, and voices that reminded her that she was outside the fold, far from the social norms that would have preferred her to be a stay-at-home mother, concerned with raising a family. She began to wonder why she couldn’t achieve stable relationships, to question what the mountain gave her and what it took from her, and to see herself buried in dark thoughts, into a form of loneliness that seemed incurable. He wanted to take his life. They helped her not to, just as she now contributes her grain of sand. After that, a real competition began between several women to be the first to win the famous 14th summit, which is a trivial matter coming from where they come from. Edorny finished second in 2010, but only a few months later, it was learned that Korean Oh Eun-sun had not reached the summit of Kangchenjunga.

Edurne’s example, as well as that of her rivals Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner, Nevis Merwe, or Oh Eun-sun, put an end to the magical aura of the group of fourteen thousand, numbering eight thousand, which now became the field of expression (on their usual routes) for tourists and travel companies. Edorn spent nine years completing the list. Reinhold Messner, the first man to achieve this, was sixteen years old. But the South Tyrol mountaineer closed that chapter in 1986: a footnote of more than two decades that illustrates the gulf between male and female existence in the mountains, a gulf that is only slightly smaller now.