Christmas is one of the most important dates in the Christian calendar and, over time, it has also become a cultural phenomenon that has crossed religious boundaries. Even for those who do not profess the Christian faith, it is a story full of symbols that dialogues with universal human issues.

In Christian tradition, Christmas celebrates the birth of Jesus. More than a religious event, this story supports the idea that the creator God takes human form in a boy born in Bethlehem. This is usually summarized by the phrase “God with us.” But the symbolic power of Christmas goes further. This God does not appear associated with power, wealth or institutional security, but with extreme vulnerability. He is, in this sense, a “God like us”.

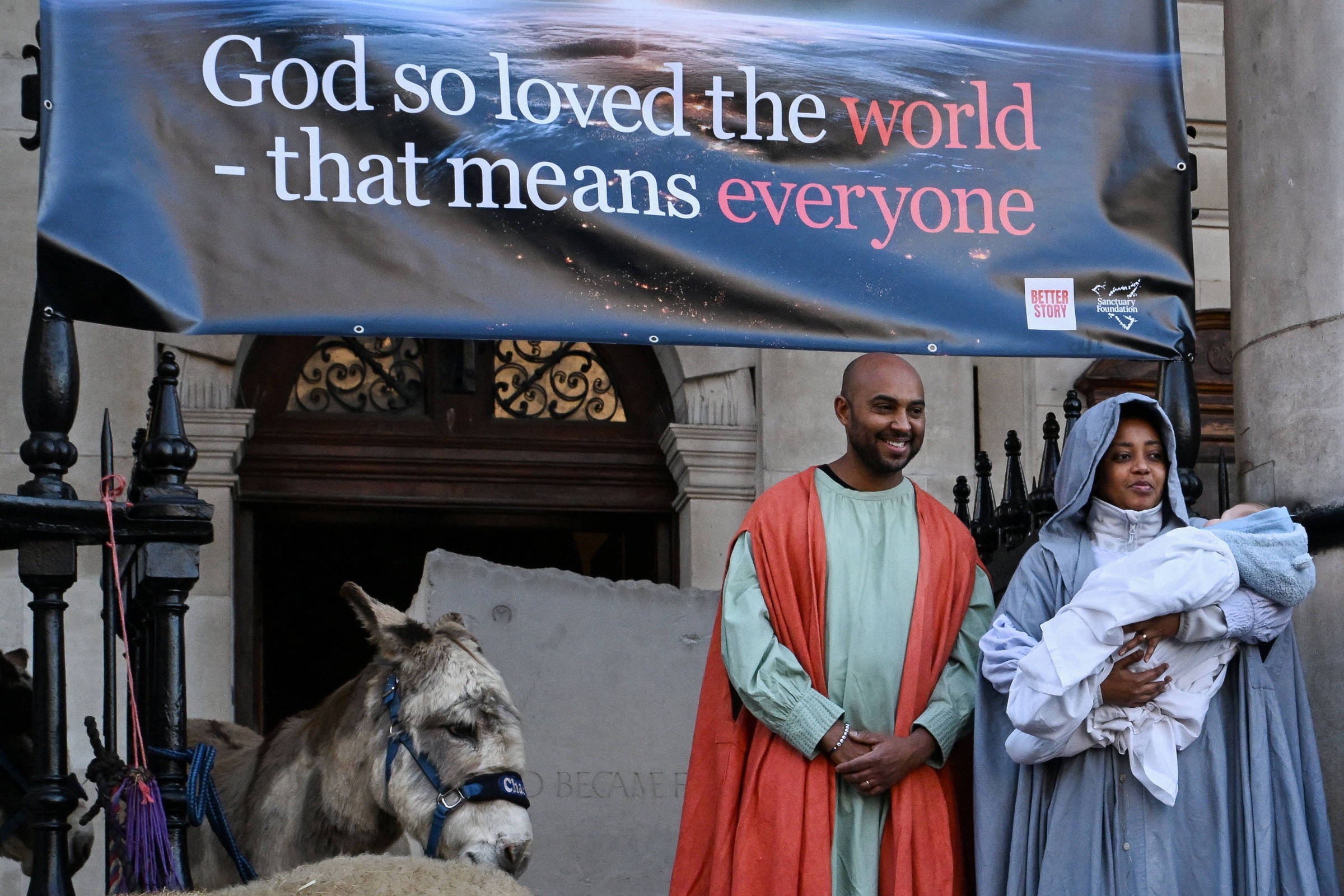

The crib is revealing. A newborn placed in a trough, outside the city’s inns, surrounded by few resources and no structural protection. Jesus was born poor, on the margins, without political or economic guarantees. This image bears witness to the reality of millions of children who are still born today in contexts of profound vulnerability, in Brazil and around the world.

Shortly after the birth, the biblical tradition presents this family as refugees, forced to leave their land because of the violence of political power. The flight to Egypt, recounted in the Gospel of Matthew, echoes the contemporary trajectories of populations displaced by wars, famine, climate crises and social conflicts. Christmas therefore does not romanticize suffering. He exposes it as part of the human condition.

The very geography of Jesus’ childhood reinforces this symbolism. He grew up in Nazareth, a small peripheral village in Galilee, a marginalized region of Israel, which in turn occupied a peripheral position in the Roman Empire. It’s a story that shifts the center. The divine is not born in palaces, but on the edges. It is not affirmed by domination, but by the proximity of the forgotten.

In adult life, this consistency remains. The story presents a persecuted man, arrested and sentenced without the right to defense. A dynamic that is still repeated today in societies marked by inequalities, where access to justice is not equal for all.

Throughout this story – from birth to death – the Christian tradition presents a God who identifies with human pain. Jesus’ life is marked by uncertainty, like someone who walks against all odds. Even the resurrection, the core of the Christian faith, appears as an affirmation of life in a scenario dominated by death.

Oppressed people experience loss every day. Stories come out of the Bible to appear, for example, in the Coqueiral neighborhood of Recife, where the church I pastor is located.

During the great flood of 2022, which hit our neighborhood particularly hard, around 2,500 houses were destroyed. People who had almost nothing lost almost everything – except the stubbornness to rebuild their lives. Resurfacing there was not a metaphor, but a necessity.

Therein lies perhaps the most enduring provocation of Christmas. That of a God who, in the Christian imagination, insists on identification with the fragile, the displaced and the disposable. In a world that celebrates success, accumulation and visibility, this narrative continues to challenge consciences – religious or not – about the lives we consider worthy of care, protection and a future.