“Cancel culture” is such a new phrase that it has no exact definition, but it is associated with a collective call to boycott someone because their positions, or their history, are considered unacceptable. Even if initially it was said that it came from the political left, or from liberalism, it can also come from the opposite side. This is what happened this Wednesday in Colombia, when the right called on the country’s businessmen to completely close the door to dialogue with Senator Iván Cepeda, left-wing presidential candidate and leading the polls. This after the Petrista politician met with businessmen affiliated with the Colombian-American Chamber of Commerce as part of what he called a “great national dialogue.” “I love that the meeting caused so much controversy,” Cepeda says by phone. “And other meetings of the same style are coming, I will announce them when they appear. Their publicity is agreed with the participants, when they want it, so I do not do it unilaterally or opportunistically.”

The first criticism leveled at businessmen for talking with Cepeda came from former President Álvaro Uribe, who sought to present the 2026 race against Petro’s candidate as a fight against “narcocommunism.” “Colombia does not need companies or unions that come to support those who want to implement Castro-Chavismo,” the politician wrote on social networks. Then he elaborated in a radio interview: “These unions and these companies are doing harm, it must be said in all truth. » The director of the Chamber, María Claudia Lacouture, former minister of Juan Manuel Santos, stressed that she represents “petrosantism”.

Uribe Vélez was followed by other presidential candidates, calling for a boycott. “Dear businessmen, we must learn to say NO, whatever the cost,” said Vicky Dávila. “It is worrying that AmCham Colombia, an organization that represents the interests of the business sector, gives a platform to figures like Iván Cepeda, whose political history aligns with the promotion of socialism, class struggle and a narrative of hatred towards the business world,” added Uribe senator Maria Fernanda Cabal. “When businessmen find themselves in the Homeland or Money dilemma, if they choose money, they find themselves without a Homeland and without money,” criticized their co-partisan Paola Holguin. “Now they open the door to anyone who represents the most extreme communist version, heir to the FARC and company,” added Uribista representative Hernán Cadavid.

This dispute between Cepeda, Uribismo and the businessmen clearly measures the temperature of the three actors at this moment in the political struggle. Uribe associates the senator with left-wing dictators such as Vladimir Lenin, Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro. His argument to businessmen is that 2026 is not just any election, but rather an election where the future of democracy is at stake, and that is why all sectors of society must take sides to the point of not speaking with Cepeda.

“Behind this call to cancel Cepeda, there is actually a call to take a stand,” says Angie González, professor of political communication and electoral campaigns at Externado University. “Businessmen are not betting on any candidate, because everything is still uncertain, it is not sure that there is one who can counterbalance the government, and they cannot help but talk with Cepeda, it would be a big risk. They are usually cautious, but the right is now putting pressure on them with the discourse that this could become Venezuela.”

Cepeda, for his part, defines this story as “a fiction”, a “manipulation of public opinion with prejudices”. He says he does not identify as a communist, although he has been active in organizations that are, and understands it as one of many “outdated concepts.” He emphasizes that he did not support an armed revolution, as his opponents call guerrilla warfare, but rather a peaceful “ethical revolution” that ends classism, racism and war. His challenge, he knows, is to challenge the perception that Petrism represents an anti-entrepreneurship view, especially after President Gustavo Petro’s growing conflicts with labor leaders such as Bruce MacMaster, director of the National Businessmen’s Association, the largest private sector organization.

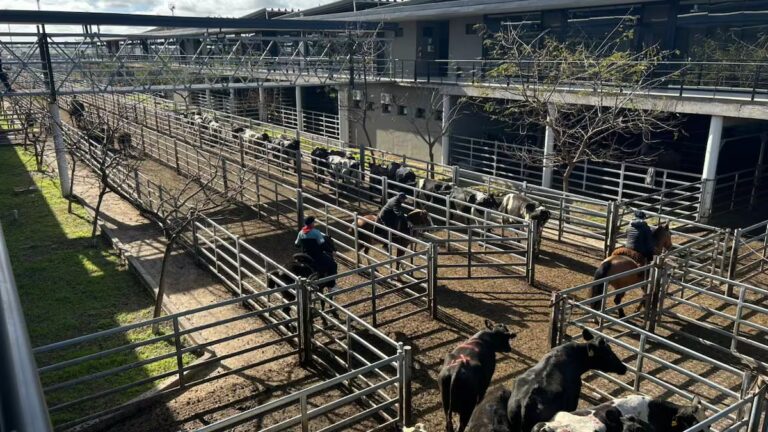

“In this government, private property was respected, thousands of companies recorded profits and, to give an example of our ability to work together, there was an agreement with the cattle breeders’ union to buy land for farmers,” Cepeda says of an alliance in which he played a key role, along with the president of said union, José Félix Lafaurie. “It’s not as successful an agreement as we would have liked, but what I emphasize is that we managed to promote social reform, agrarian reform, without violence and with an agreement with businessmen. Now we are starting conversations with them that will melt the ice. So that I listen to the prejudices that they have against me, and them what I may have against them. I want us to have a real and sincere dialogue.”

Cepeda likes to highlight his role as a peace negotiator in his profile, both in the Santos government and in the current one. As a political leader, he offers civil society what he has offered for years to those who were armed: to sit down and reach agreements. This was called the national dialogue, where everyone from businessmen to social leaders would sit. “We want to reach an agreement and, if we reach it, we will sign it and find the implementation mechanisms. I have seen good dispositions on the part of businessmen, there are people engaged in an exploratory way,” he says.

Colombia’s business community has not always supported the hard right that Uribismo represents: some supported Santos in his clash against the right-wing former president, and in the previous campaign several reached out to Petro. But the vast majority supported Álvaro Uribe when he was president, and now he wants to rekindle that affinity by portraying Cepeda as a Chávez. Meanwhile, the left-wing candidate is knocking on the doors of investors who are calculating their best position on the next president.