The daughter of the man considered the biggest serial abuser associated with the Anglican Church says finally discovering the truth about her father’s attacks on around 130 boys has been shocking and horrific.

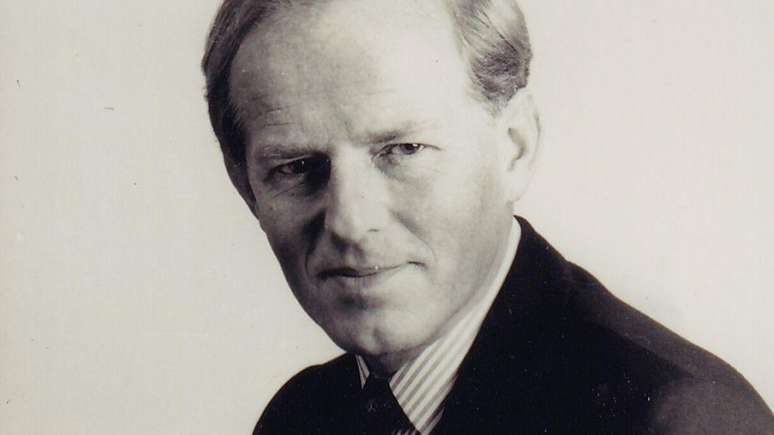

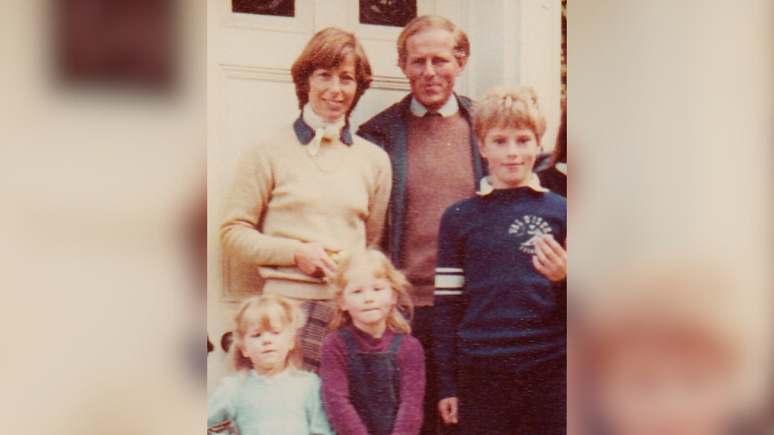

Fiona Rugg, 47, is the youngest daughter of lawyer and Christian charity chairman John Smyth QC, who died before being brought to justice.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Smyth subjected approximately 130 boys and young men to extreme physical and sexual abuse, which he presented as a form of spiritual discipline.

Since then, Rugg, who now lives in Bristol, United Kingdom, has gradually assimilated the seriousness of the facts, but says he has often faced a feeling that he defines as “shame by association”.

“Rationally, I know it’s not my fault, but you feel guilty that your father could do that to someone and besides, he never showed regret,” she said.

“A lot of my father’s story and how he evaded responsibility involved cover-ups and deception. But I want to address that and bring it all to light.”

The so-called Makin Report, published in 2024, concluded that the Anglican Church’s handling of the matter represented a cover-up of the allegations against Smyth.

One of the clergy involved even admitted, “I thought it would do immense damage to God’s work if it became public.” »

Speaking openly to the BBC for the first time, Rugg said understanding the extent of her father’s “shocking” abuse had helped her heal.

“I have forgiven him, but that doesn’t take away the pain or make what he did acceptable. I no longer feel trapped or ashamed, but that doesn’t lessen the horror of his actions,” she said.

“On his part, there was no sign of regret. I apologize, on behalf of my father, for what he did to those boys.”

Warning: This report contains sensitive content and references to child abuse.

Rugg recalls an oppressive childhood, marked by what he describes as constant “hypervigilance” to his father’s unpredictable moods.

“I think the predominant feeling was actually fear, for as long as I can remember,” he recalls. “I was afraid around my father, he was very unstable.”

“He would get very angry, and there was this feeling of emotional instability, of walking on eggshells, of trying to guess what his mood would be. A feeling of guilt, because when I was a child I didn’t like my father and sometimes I hated him.”

Rugg said her father “completely ignored” her when she was a child, to the point of making her question her own judgment about her “unstable” character.

“What I saw confused me,” he said. “He was so scary and angry and cruel, so difficult to deal with. I wanted to get as far away from him as possible, but what I saw at the same time were people who adored him.”

As Smyth laughed and played outside with boys and young men in the sun, she watched from the window, after being told to keep her distance as it was considered an “unwelcome distraction”.

“We lived with a completely different John Smyth than the one he presented to the world,” he explained.

“When you’re a child, the natural conclusion is to think, ‘He must be right, and I must be the problem. I’m the one who’s not seeing things correctly.'”

Smyth gained access to Winchester College in England in 1973 through the school’s Christian union and began abusing students after inviting them to Sunday lunches at his family’s home.

He forced his victims to strip naked and endure violent caning sessions in a soundproof warehouse on the grounds of his residence, where he attacked them with such intensity that they bled.

An evangelical Christian, Smyth presented abuse as a form of punishment and repentance for supposed “sins” such as pride or masturbation.

An internal investigation by the Iwerne Trust revealed the scandal in 1982, describing the attacks as “prolific, brutal and horrific”, detailing how eight of the boys received a total of 14,000 lashes.

But instead of reporting to authorities, high-ranking evangelical officials in the Church of England facilitated Smyth’s quiet departure from the United Kingdom, allowing him to evade justice for decades.

When the family was taken to Zimbabwe, in southern Africa, in 1984, Rugg says his father presented the move as “noble work,” a sacrifice of his “brilliant career” to serve as a missionary.

But the trail of destruction followed him across the world. Soon after, he began organizing Christian camps in which he forced boys to be naked and beat them.

The following year, tragedy struck. A 16-year-old boy named Guide Nyachuru was found dead at one of Smyth’s camps less than 12 hours after arriving at the site. The case resulted in a manslaughter charge, but the case was eventually dropped.

When he returned to live in England at the age of 18, Rugg began to ask more and more questions about his father.

“Sometimes, people would say that I was my father’s daughter and I would see a shadow pass over people’s faces,” she remembers.

“The reactions weren’t ‘oh, what a nice man’. It was the opposite. There was absolute silence. There seemed to be little connection with the UK, which always struck me as strange.”

She confronted her father about the rumors on Christmas Eve. The reaction was an explosion of fury: he accused her of being “disloyal” to the family for daring to question their integrity.

“His reaction was so extreme that I remember thinking, ‘Well, now I’m sure of it.’ There’s never so much smoke without fire,” he said.

Complaints about Smyth’s abuse were first made public in February 2017, following an investigation by Britain’s Channel 4.

One night, Rugg turned on the television and found his father’s face on the screen, with his name associated with horrific crimes.

“They were young, vulnerable children whose lives were destroyed. I have a son,” he added.

“As cruel as I saw him be, I had no idea he had committed so much criminal abuse. It was horrible and shocking, but at the same time it all started to make sense.”

“His whole life was about doing ‘the work of the Lord’. Everything was justified by his Christian faith and I found this hypocrisy truly repugnant.”

In August 2018, Smyth received a summons from Hampshire Police to return to England and make a statement, under threat of extradition.

Eight days later, he died of heart failure, at the age of 77, without ever being held legally responsible for the trauma inflicted on the boys in his care.

Rugg said that today he can talk about his father “without bitterness or hatred” and that he finally feels at peace.

“In my experience, if you face what your father did, it is possible to heal and then forgive,” he explained.

“There are still moments of sadness, but I no longer feel this knot in my stomach when I think of him, and that’s progress. It’s not something I have to carry or something I have to be controlled by.”

“It stopped being something that was imposed on me, to ‘I choose what to do with it’.”