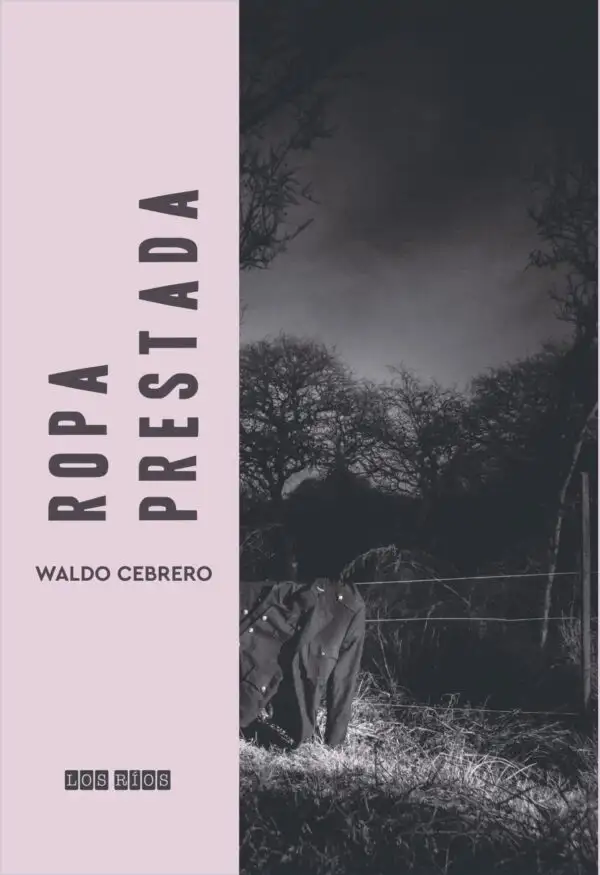

Waldo Cebrero He was born in San Carlos Minas in 1983, trained as a journalist and now spends his time between university lectures and writing workshops. For years he reported on trials for crimes against humanity and legal cases related to illegal repression in Córdoba.

A very intimate story emerges from this experience borrowed clothesa non-fiction book published by Los Ríos publishing house in which chronicle, essay and autobiography overlap.

The starting point is a blunt object: the dress uniform of Raul Pedro Telleldin, Founder and Head of the Information Department of the Police of Córdoba (D2)one of the key elements of the repressive apparatus that operated in the USA Santa Catalina Passage during the dictatorship.

This uniform that belonged to the man many called “Menendez” from the provincial police, ended up hanging in Cebrero’s closet in his own house for a decade.

the book follows the journalistic research that led the author to interview victims and oppressors, including Telleldín’s son Carlos, who presents him with the garment with a clear mandate: to bring it to “his father’s museum.”in relation to Provincial Memorial Archives. The organism’s reaction leaves the author alone with the uniform that no one wants to accommodate.

The plot becomes even more personal when the narrator recognizes himself as the son, grandson and brother of police officers, growing up in northwest Córdoba, a region he describes as a “police factory.”

The arrival of her second daughter, Elena, and her partner’s request that this article of clothing not coexist with the girl drives the writing forward: getting rid of the uniform also implies the question of what to do with this family legacy and with the violence – past and present – that surrounds the police institution.

In dialogue with After Office (point-to-point radio, FM 90.7)Cebrero gives a look back at the story behind it borrowed clothesreconstructs the figure of Telleldín, tells what it was like to live in that uniform for ten years and reflects on how Córdoba continues to process or avoid memories of its own police force.

Economics in Córdoba: the lens that makes the new poor workers visible

The “Menéndez” of the Córdoba Police

—Who was Raúl Pedro Telleldín, the owner of this uniform?

– Raúl Pedro Telleldín was something like the Menéndez of the Córdoba Police during the dictatorship: the founder and head of the D2 secret service, which operated in the Santa Catalina Passage and was the operational and intelligence organ of the police to kidnap, disappear, rob and loot.

He was also the author of an internal police purge during the dictatorship, in which about twelve police officers, including Alvareda, Fermín and Robles, were kidnapped and murdered.

Since he died in 1983, he was a figure who remained in the shadows at the beginning of the trials: he had been the leader of all the convicted police officers.

His surname gained historical notoriety after the attack on the AMIA, when his son, Carlos Telleldín, was accused of being responsible for the delivery of the van that blew up the AMIA, for which he was later acquitted. This is the owner of the uniform: Raúl, Carlos’ father.

The uniform that no one wanted and that was in the closet

—In the book you talk about your own connection to this uniform. What was your encounter with this piece of clothing and what path did you take to get to “Borrowed Clothes”?

– I have been wearing this uniform for ten years. I am a journalist who has researched and reported on trials for crimes against humanity. The topic interested me, I am interested in this topic. At that moment, with a different intention and a different aesthetic, I began researching to create a biography of sorts.

In this investigation, I spoke to many of Telleldín’s oppressors and also victims. I interviewed Carlos, I was living in Buenos Aires, and one day Carlos told me: “I have my father’s uniform, take it to my father’s museum.” From his point of view, the memory archive is his father’s “museum”.

With this idea in mind, I brought the uniform with me. It seemed to me that as an archive they were archiving things, not just documents, and the uniform could have a place there even if it wasn’t on display. However, at that time the file was in the middle of an administrative transition and they were unable to obtain it.

We had a detailed conversation and they told me: “This is in memory of the victims.” I think this is part of the work of the archive and the response has been very good. In fact, I also submitted other documents that I found during the investigation.

The thing is, I kept the uniform. I moved and the uniform started hanging in my closet. I was left with something that wasn’t mine, but that I had made mine.

—There is also the reading that the repressor’s son considers this room as “Papa’s museum”, while the archive decides not to accept the uniform. How did you experience this tension?

– For the son, this place is the father’s museum: “My old man’s story, look at it.” And the archive, on the other hand, takes the position that this is a place to tell the story of the victims.

They rejected my uniform, said no, and in the spirit of the book that makes up the uniform I own: I had it and I have it and I have to do something with it. After ten years of living with this thing hanging in my house not in a package but as a piece of clothing, I asked myself another question: I have always lived with uniforms.

As the son of police officers in the northwest of Córdoba

—Why do you say that you have always lived in uniform?

– Because I am the son of police officers, the grandson of police officers, the brother of a police officer, a high school classmate of many police officers. I come from the northwest of Córdoba, an area that is a police factory because there are not many work areas. I always rejected the opportunity to become a police officer.

This uniform put me in front of the family mirror. And the twist I was able to give the book was to abandon the journalistic balance sheet that I wanted to have at the beginning. In the end, a kind of chronicle was created in which you can see a small part of Telleldín’s life, but also my own journey to get rid of this uniform and at the same time tell what it’s like to be the son of a police officer.

Carlos appears there as the son of a police officer; Fernando Alvareda appears, son of another police officer, in this case Telleldín’s victim; and I appear and try to understand both.

—The plot is permeated by something very intimate: your partner’s mandate and the arrival of your second daughter. How does this fit into the book?

—The plot of the non-fiction book is based on my partner’s assignment. She, pregnant, tells me, “When Elena is born, I don’t want her to be here,” referring to the uniform. Elena is my second girl.

The story is then told as the appearance of the narrator’s second daughter approaches. You have to get rid of this story and also the object. The book tells about this process: what I do with the uniform, what I do with what it stands for and how it all mixes with my family biography.

The destination of the garment and what it leaves behind

– What can you say about the fate of the uniform without spoiling the book? Do you know what you’re going to do with it?

—There is also an ending to the uniform in the book. I will return it because his family asked me to. Maybe I can do it if the opportunities are there; It could also happen that it takes another ten years or that the file finally gets it, I don’t know.

What I can say is that it is no longer in my house: I haven’t had it with me for two years. It’s in other places.

– In the last part you talk about this uniform as a personal “file”. Do you feel like you’ve kept the word you gave your partner?

– Yes, at least I kept that word. I don’t experience it as an absolutely cursed object. As I can tell you, I’m a pro at this and it always seemed to me that objects convey things, they convey stories, full of very painful stories of course, but they are still an archive of all that for me.

The uniform served me, if you will, to ward off a little both the historical pain – which I experienced neither as an immediate family member nor as a protagonist, because I was born after that time – and the personal pain.

It allowed me to take a look at what was happening in Córdoba in the 70s and also to take a look at new violence that was being recycled in the police, other forms of coexistence with a police officer who is your family. A little bit of everything in the book.