One day, Stalin’s two youngest sons, Vasily and Artem Sergeyev, let the wind blow away the pages of the old history book they were studying. It was an oversight as they joked outside, but her father just appeared with a … of some friends. The dictator grabbed them by the arm and told them about the thousands of years of knowledge they contained, the blood, sweat, and tears it had taken to gather that information, and the decades of work invested by their authors to arrange the pages so that they would learn something. Finally, he ordered them to rearrange the pages and, before leaving, added: “You have done well. “Now you know how to deal with books.

Stalin’s love of literature began when he was a child and did not diminish throughout his life, even if this facet has been little studied by his biographers. Unlike other dictators like Hitler, the idea of burning books never occurred to the Soviet leader. He would surely have agreed with Victor Hugo’s response to the Paris Communards when they burned the Louvre library in 1871: “Have you forgotten that your liberator is the book?”

Stalin collected books with the same passion as he collected battles. Of Marx has Balzacof Lenin has Shakespeareof Emile Zola has HG Wellsof Joseph Conrad has Winston Churchill. When Artem was seven years old, he gave him a copy of “Robinson Crusoe” (1719), the famous adventure novel by Daniel Defoe. “For my little friend Tomik, with the wish that he becomes a conscious, firm and courageous Bolshevik,” he writes on the first page. At the age of eight, he gave her a copy of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Jungle Book” (1894).

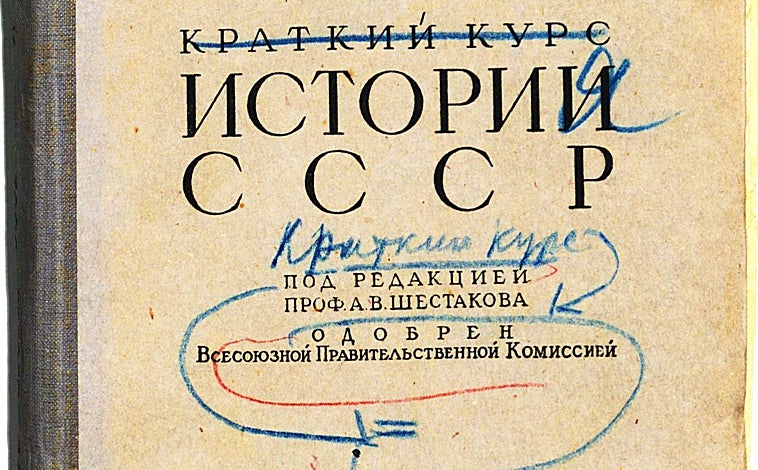

Vasili, for his part, received a Russian translation of “Air War 1936” when he began serving in the Air Force during World War II. He didn’t care at all that the author of this work of fiction, German pilot Robert Knauss, served the Nazis. You could learn a lesson from any book, even if it was written by an enemy. He also entrusted him with a work whose composition he personally supervised and edited: “History of the Communist Party of the USSR” (1938).

The power

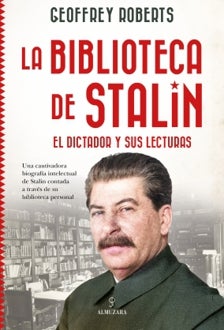

“He read above all to learn what was useful for the exercise of power, but also out of a simple desire to have fun and have fun. It is true that the evaluation of everything I read was political. For him, great literature was that which contributed in one way or another to the cause of communism. This is not to say that the work had to be purely socialist in its content, but it did in some way raise awareness of a progressive future,” Geoffrey Roberts, who has just published “Stalin’s Library” (Almuzara), tells ABC.

The professor of history at the University of Cork, a member of the Royal Irish Academy and one of the world’s leading experts on the Soviet Union, explores the intellectual life of the Soviet leader by asking two questions: How could such a voracious reader become one of the most feared and bloodthirsty dictators of the 20th century? And why has this whole culture not appeased its desire for repression? What is exceptional about this essay is that Roberts responds through the tyrant’s personal library, which housed over 25,000 books.

“It is true that Stalin persecuted writers and intellectuals he considered a threat to the communist system, but he did the same to other groups. The Communist Party and state bureaucrats suffered as much as the writers, because their maxim was to defend Soviet socialism. This is why the vast majority of his victims were peasants or members of ethnic groups living in the Soviet peripheries, whom he considered ideologically unreliable due to the influences they received from nationalism. However, we must not forget that intellectuals played a leading role in propagating the projected image of the ‘Great Purge’, as their friends and family preserved and publicized their stories of victims of repression,” comments the author.

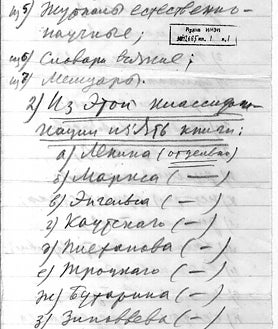

Persecuted and executed

In 1962, journalist Ilya Ehrenburg wrote in the magazine “Novy Mir” that of the 700 authors who participated in the first congress of the Writers’ Union of the USSR in 1934, only 50 survived to see the second in 1954. In 1988, Vitaly Shentalinsky gave the figure of 2,000 writers detained and 1,500 executed or died in prison, although he later increased this figure to more. over 3,000 and 2,000 respectively. Joseph Brodsky, one of the most important Soviet poets, stated in 1981 that “in the 1930s and 1940s, Stalin’s regime produced writers’ widows so efficiently that there were enough of them to organize a union.”

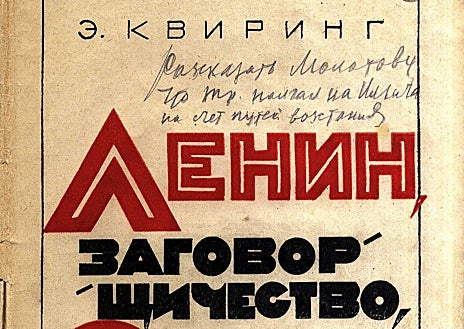

During this time, the dictator read everything he could get his hands on, including military history books. “He learned as much from his favorite writers as from his enemies. Trotsky was his greatest rival after Lenin’s death, but he continued to read his writings and draw positive lessons from them, as well as ammunition with which to attack him. And although his favorite author was always Lenin, he deeply admired the works of Robert Vipper, even though he was far from a Marxist historian. He gained much of his understanding of Russian history from the book he dedicated to Ivan the Terrible in 1922,” warns Roberts.

He also read a lot of fiction. His library contained thousands of novels, plays, short story compilations, film scripts and collections of poetry. The famous Russian poet Osip Mandelshtam repeatedly spoke of the immense respect Stalin had for poetry, without knowing that he himself would be arrested shortly after for reciting verses critical of the regime and that he would die in a concentration camp in Siberia. “When they took him away,” said his wife, the writer Nadezhda Mandelshtam, “I asked myself the forbidden question: Why did they arrest him?” According to our legal rules, all motives were possible: his poetry, his statements on literature or the poem against Stalin.

The first thousand

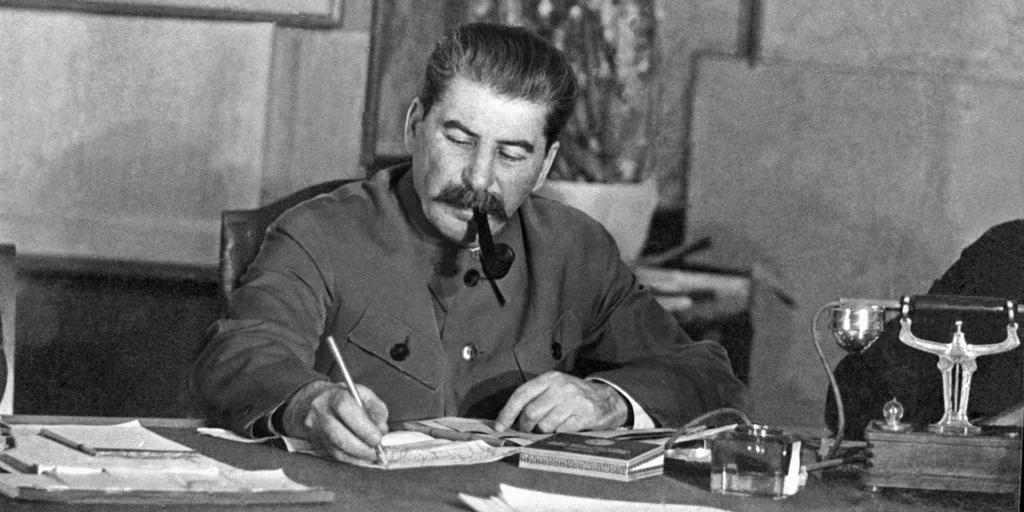

Before coming to power, he already had a thousand works. In the mid-1920s, as their numbers increased, the dictator gave them their own identity with a personal seal that he placed on each copy: “JV Stalin Library”. He also designed his own classification system and employed the services of a librarian. The main room of his dacha – country house – in Moscow was a large room which he devoted exclusively to the storage of books, although most of his extensive collection was in an adjacent building. “There is no doubt that the tyrant was an intellectual devoted to endless reading, writing and editing, although it is true that given the scale of his misdeeds, it is normal to imagine him as a monster,” the author emphasizes.

-

Author:

Geoffrey Roberts -

Editorial:

Almuzara -

Pages:

336 -

Price:

29.95 euros

His obsession was such that his body remained for several days on the sofa in this library, surrounded by books. He had had a heart attack and none of his assistants dared to enter for fear of interrupting his readings. Dmitry Shepilov, editor-in-chief of the newspaper “Pravda” and later Minister of Foreign Affairs, visited the dacha the day after the discovery of the tyrant’s body and described the room as follows: “It was a large desk with another placed against it forming a T, both filled with books, manuscripts and papers stacked on their boards, like the small tables arranged around the room.

The collection could have remained intact, but plans to turn the dacha into a museum dedicated to Stalin were postponed when Khrushchev denounced his repressive practices and cult of personality at the 20th Communist Party Congress in Moscow in February 1956. According to Roberts, who has followed his trail for decades, Stalin’s more than 25,000 books were distributed among other libraries, although significant remnants survive in the group’s archives, where Four hundred texts marked and annotated by the same dictator that the historian studied in detail stands out.

“My attention was drawn to a 1945 book on constitutional law in capitalist countries, which the dictator read with great interest, especially the section devoted to the Constitution of the United States. At the end of World War II, Stalin was considering radical changes to the Soviet constitution and was interested in what lessons he could learn from the experiences of other countries. Unfortunately, any chance of change was thwarted by the outbreak of the Cold War and the resurgence of repression in the USSR following the relative liberalization that occurred during the war,” Roberts recalls.