Abracadabra and it was time and here “The Magician” reappears. And with him the genius and the somewhat missing figure – like that of Anthony Burgess or John Updike or Saul Bellow and many others – of John Fowles (UK, 1926-2005). finished and … very consumed in its moment of conjuring in these increasingly distant times when, among the “bestsellers” at the top of the lists, the most “best” also appeared among the same “sellers”.

“In fact, I never wanted to be a writer,” writes the Englishman in the introduction to “Wormholes” (wormholes, 1998), his last book published during his lifetime, a compilation of essays and obsessions. And yes, now my wish is almost granted. Because Fowles, who always defined himself as “an outsider”, does not seem to figure in any canon and is not recognized as a beacon by any young narrator (and perhaps the posthumous publication of his diaries, filled with very “British” and homophobic and anti-Semitic comments, contributed to this). But yes: the good times when this man published a work where one could detect glimpses of Shakespeare, George Eliot, Tolstoy, Mann and the great and ancient Greek philosophers without that stopping him from “having fun” and having fun playing all the styles.

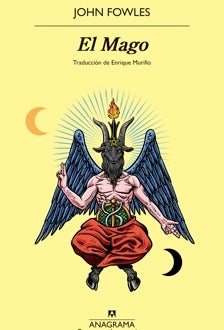

-

Author

John Fowles -

Translation

Enrique Murillo -

Editorial

Anagram -

Year

2025 -

Pages

680 -

Price

26:90

Thus, his beginnings with the quasi-founding character of serial killer love in the quasi-Nabokovian “The Collector” (1963 and, we learned, an instruction manual for more than one real-life Hannibal Lecter); the period metafiction and the very successful postmodern pastiche in “The French Lieutenant’s Lover” (1969); the terrific storybook and conceptual novel “The Ebony Tower” (1974); the great Hardy-style novel of the 19th century updated in “Daniel Martin” (1977); the refined pornography of “Mantissa” (1982); or the quasi-Pynchonian historical novel with a touch of science fiction in “Capricho” (1985). But he is above all – although Fowles never considered him the best among his people; Thus, the first to complete but the second to appear on the scene, he published it in 1966 and revised it extensively in 1978 – “The Magician”, original title “The Godgame”.

At the time, “The Magician” was hallowed and admired as an addictive cult novel embraced worldwide by the Aquarian generation (and also, it usually happens, it resulted in a terrible movie shot in Majorca with Michael Caine and Anthony Quinn in the lead roles; a TV series in the works for years could correct this absurdity which, of course, is today adored by the most crazy and psychotropic moviegoers). In the meantime and until then, here it is again wonderful road novel of ideas and whose roots – Fowles did not hesitate to recognize this – sank into the very firm and fertile soil of two brilliant novels of which the air of the visitor and the host were the key: “Great Expectations”, by Charles Dickens and, especially, adored by Fowles, “Le Grand Meaulnes”, by Alain-Fournier.

Over the years, somewhat disconcerted by the book’s fame, Fowles tried to dampen this enthusiasm.

To these precedents, Fowles added Mediterranean eroticism, post-beatnik impulses, nomadic mysticism, a touch of Elizabethan fantasy from “The Tempest”, “up-to-date” psychology, Chatwinian tourist postcards, secular eroticism and Hellenic mythology, achieving something that is today read and appreciated anew as a kind of missing link between Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”, “The Great Gatsby” of Fitzgerald, the Herman Hesse of ‘Steppenwolf’ and ‘The Bead Game’ with the Donna Tartt of ‘The Secret History’ and the Peter Straub of ‘The Camera Obscura’ sprinkled with magic dust of the David Lynch of ‘Twin Peaks’ and ‘Lost’ of JJ Abrams and the Stanley Kubrick of ‘Eyes Wide Shut’.

Suicidal crisis

Here, young professor and Oxford graduate Nicholas Urfe (with more than one trait of his authorship) goes through a near-suicidal crisis when he discovers he is not and will not be a great poet and abandons his love Alison and seeks to reinvent himself as an English teacher on a Greek island. There, the hypnotic Maurice Conchis: a wealthy Greek-British who may or may not have been a Nazi collaborator and who now lives isolated in his temple-palace. Then, psycho-mental-sexual-dialectical duel with Conchis as Sadistic manipulative puppeteer masterful with Urfe, his dedicated puppet. Throughout the scenes and rituals where two irresistible and almost vampiric local priestesses also appear – Urfe returning to London – discover that nothing was what it seemed in this trance: that a dead woman is alive, that he himself has been born again, that he is no longer who he was or thought he was. And a final revelation – a definitive and perhaps vindicating prestige – will reveal a past in which the illusionist succumbed to his illusions.

Fowles was born in 1926 in Leigh-on-Sea, a small civil parish in the county of Essex. He sums up his childhood in a single sentence: “Since then, I’ve been trying to escape it. »

Over the years – somewhat disconcerted by the book’s fame – Fowles attempted to temper this enthusiasm by asserting that “this will remain essentially a adolescence novel written by a late adolescent”. What so many other great novels are also accused of, including the magnum opus of Salinger, Kerouac and Cortázar. Magical novels like magic. Novels without tricks. Novels which, when reading them, one can only wonder how their conjurers managed to understand in a few pages that the best, the wisest, is to relax and let oneself be carried away (like Urfe de Conchis) by their numerous sleight of hand and to be happy that someone has performed them before us. Novels that invite us to everything here and everything there and presto!