For centuries, the Bayeux Tapestry has been interpreted as a work designed for monumental spaceslinked to cathedrals or large aristocratic halls. However, a recent research raise a different hypothesis: The famous 11th century embroidery was perhaps intended to be hung in a monastic refectory, where monks gazed at it while listening to readings during meals. This proposal allows us to better explain both its physical characteristics and its complex narrative structure.

The study, published in Historical researchplace it origin of the Tapestry in CanterburyEngland, probably around the monastery of Saint-Augustin Abbeyshortly after the Norman Conquest of England. There existed a monastic community equipped with the technical means, intellectual knowledge and visual tradition necessary to produce a work of such magnitude. The author of the research, Professor Benjamin Pohl from the university’s history department, also points out the role of Father Scolland as key figure in the reorganization of the monastery after 1066 and how possible promoter of the project.

Practicality is one of the main disadvantages

One of main problems of the traditional interpretation is practical. The covering measures more than 68 meters long And weighs approximately 350 kiloswhich would have made its continuous and legible display extremely difficult in a Romanesque church, fragmented by columns and arches. To this is added that many of his scenes and especially its Latin inscriptions would be out of the viewer’s field of vision in a large space.

The question of readability is at the heart of the new hypothesis. The embroidery contains 58 inscriptions identifying characters, places and actions, and uses terms such as hic (“here”) or Ubi (“where”), which refer to a guided reading of the image. According to the study, this combination of text and image requires close and prolonged observationsomething not very compatible with a cathedral nave, but entirely consistent with a refectory.

Who was it addressed to?

In medieval monasteries, the refectory It was a space of ritual silence in which monks ate while listening to historical, biblical or moral readings, according to the Rule of Saint Benedict. The walls of these dining rooms were once decorated with narrative images which accompanied this exercise in memory and contemplation. The article documents numerous examples of European refectories, including several Norman ones, whose continuous surfaces allowed large textiles to be hung at eye level.

This reinterpretation also redefines the audience for which the Tapestry was intended. Against the idea of an aristocratic public, the study argues that the level of understanding of Latin used designates a monastic community. Additionally, the tone of the story is sober and not triumphant: he does not glorify William the Conqueror without nuance nor demonize Haroldbut presents the facts ambiguouslyinviting moral reflection on power, oaths and violence.

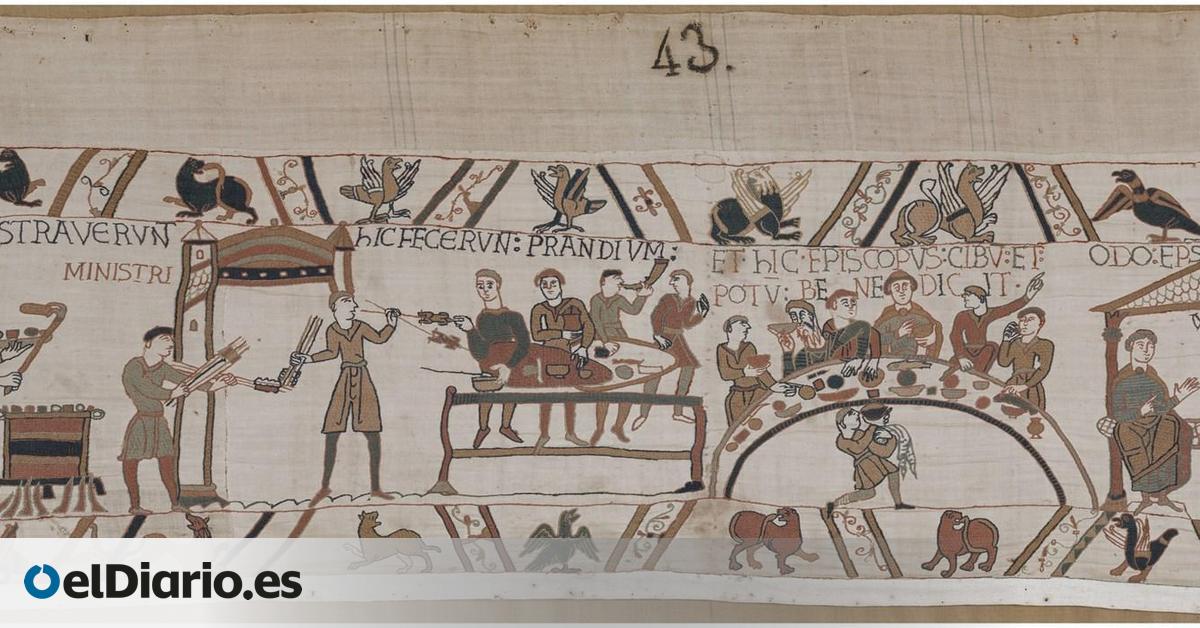

The author even emphasizes internal parallels in the work itself. In one of the best-known scenes, two banquets confront each other: a noisy one, featuring Norman soldiers, and another quiet one, presided over by Bishop Odo, where the guests eat fish and communicate with gestures. This second scene faithfully reproduces the rules of the monastic refectory, reinforcing the link between embroidery and this environment.

Seen from this angle, the Bayeux Tapestry would not have been a object of thought impress from a distance, but to accompany the ritual repetition of the historical narrative, day after day. Its possible exhibition in an internal and non-permanent space also helps to explain the rarity of the first documentary references. More than a monumental chronicle, embroidery thus appears as a collective memory toolintended to be observed, listened to and slowly “digested” by a monastic community.