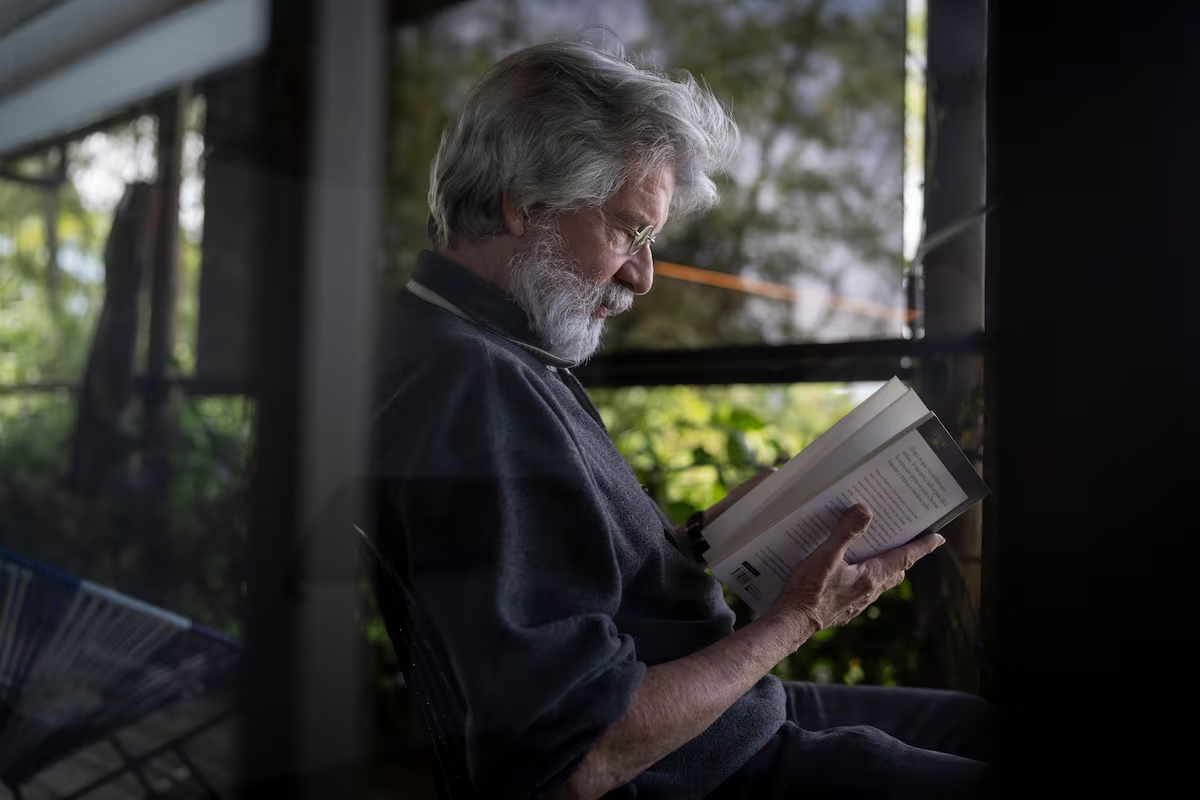

It speaks very well of Tomás González that, when asked about his leadership in literature, he responded that he did not have a leader’s profile and that the only thing that interested him was not to let the novel that he writes from his home in Guatapé cool, as he was responding to the interviews that took place against him for the Manuel Rojas Story Prize, which he has just won in Chile, and for the publication of his latest book, View from the abyss. Its title shows that, in his maturity – if not already since the publication of his first novel, First there was the seaand in sustained, honest and persistent work, without too much advertising noise and without even appearing in the soup -, González continues to reveal to us something that brings us closer to what is primordial, to the very essence of things.

Born in Envigade, from a large family populated by women, and nephew of Fernando Gómez Ochoa, one of the most important Colombian thinkers, this writer born in 1950 has published a dozen novels, half of them short stories and a collection of poetry. He has the gift of writing any of the three genres in such an astonishing and simple way that it is hard to believe that he abandoned engineering – the respected career in his family – because “he didn’t have the precision for mathematics,” when he makes each word carry an exact weight, so that the entire structure remains strong and also beautiful, without finishes or ornaments.

González has continued to approach what is important with the simplicity of words and life itself since he published First there was the sea. It was the time when he moved to Bogota to study philosophy (a degree he also didn’t graduate from) and worked as a bartender at the legendary salsa bar El goce pagano, while his wife supported him as the most loyal of customers. And although the title of his first work was once imperfect, this immense body of water continues to feature in many of his stories, not only as a backdrop but as witness to a youthful dream that turns into a nightmare.

The words with which he reflected on the importance of his uncle could be perfectly applied to describe him himself: “Neither the best nor the worst, but the most personal and independent of any pretension, pose or affiliation. » The kind of revelations that suddenly appear in its pages never have a political connotation or a fashionable subject. Everything happens and nothing happens in the narrative universe of Tomás González. They only shed light on a few very simple certainties because, as he himself says, “sometimes fiction is closer to the truth of things than the facts themselves”.

González marks the passage of human time from the gestation of a calf in the belly of a cow, the irreconcilable distance that arises in a couple from a piece of chalk with which they divide the spaces of the house they share, or the resentment towards an authoritarian father through a storm. The most complex human relationships unfold before the reader during a family trip to the sea to take the foolish old matron to see the whales, or during a road trip to help a son perform euthanasia. His work is, yes, full of water and green, perhaps because of his numerous trips to the Pacific, because he lived for a long time surrounded by the exuberant vegetation that arises in Cachipay, or because for years he experienced the voracity of the concrete jungle that is New York, where he emigrated with his wife and worked as proofreader and translator for a magazine directed by Heriberto Fiorillo, although before that he had to do a forced passage through a “culturally arid” Miami. and with very spiritual horizons.” narrow.”

And it’s not that González claims to be a guru. There are leaders who do not want anyone to follow them. They don’t mind us talking about it because everything they wanted to say, they already wrote it down. Their work is the valve that protects them from the world and, at the same time, connects them. This is Tomas Gonzalez. Under his pen, the contemplation of the most trivial and traditional reality is transformed into a deep, intimate and universal portrait that allows us to see the poem that is happening in our lives and which goes unnoticed while we fill it with influencers or very serious problems that do not really matter.

Margaret Atwood said it well: “Being interested in a writer because you like what they write is like being interested in a goose because you like what they write.” Foie gras“Among so many dazzling, bombastic celebrities that social media (and often publishers) produce, González’s work is a beacon for those of us who read (and write) in search of something beyond a well-told story, and that has to do with the architecture of words and the beauty of things somehow illuminated by them. Long live Tomás González and his work.