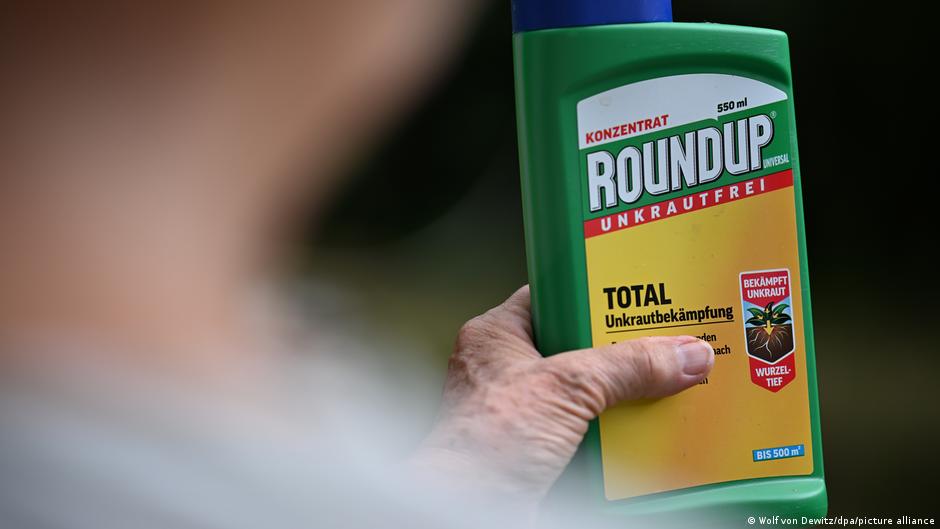

In the last seven years, there have been nearly 200,000 lawsuits in U.S. courts against Bayer’s herbicide Roundup. The protracted legal battle becomes the nerve center of American politics.

During Joe Biden’s administration, the U.S. Department of Justice allowed Roundup consumers to seek damages against the German chemical giant, with most cases related to the development of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) after prolonged exposure to the pesticide.

However, earlier this month, President Donald Trump’s administration changed that stance. After the U.S. Supreme Court sought the attorney general’s opinion, the Justice Department sided with Bayer and called for a limit on the thousands of lawsuits still pending.

Bayer has already paid around $10 billion (8.53 billion euros) to settle cancer disputes in the United States. In July, the company said it would provide an additional 1.2 billion euros ($1.41 billion) to cover compensation.

Bayer acquired Roundup in 2018 as part of its $63 billion purchase of Monsanto, the American agricultural giant known for its genetically modified seeds and controversial agrochemicals.

States confront the federal government

Biden’s Justice Department argued at the time that federal pesticide law did not protect Bayer from lawsuits in state courts because legal liability and consumer protection are traditionally the responsibility of states.

The plaintiffs include farmers and amateur gardeners. The lawsuits, filed under state law, allege that Roundup’s active ingredient glyphosate causes cancer and that Bayer failed to provide adequate warnings.

Lawsuits represent a costly burden for the industry

In contrast, the Trump administration has now asked the Supreme Court to accept Bayer’s argument that federal law preempts these lawsuits, which would significantly limit the scope for the remaining approximately 65,000 plaintiffs.

Trump’s team has also framed the Roundup litigation as an unnecessary burden on the company, exposing Bayer to massive and unpredictable liabilities even though the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has approved its products.

Critics have criticized Trump’s stance as favoring corporate interests over justice for plaintiffs, many of whom claim to be terminally ill or severely disabled.

“This trend of restricting civil liberties by far-right governments (like Trump’s) is … frightening,” Martin Dermine, executive director of PAN Europe, a network of NGOs working to eliminate dangerous pesticides and promote sustainable agriculture, told DW.

Other critics of Trump’s stance argue that this reversal represents a failure to protect public health and weakens authority at the state level because overturning the measure in favor of Bayer deprives local courts of their ability to hold companies accountable.

Bayer calls for an end to the controversy

The German pharmaceutical and biotech giant claims Roundup is safe for human use and defends the product, citing decades of studies. However, that argument has been weakened by claims that one of these ghostwritten studies uncovers other ethical problems at Monsanto.

Nevertheless, the vast majority of regulatory authorities worldwide continue to classify glyphosate as non-carcinogenic when used as directed.

Bayer CEO Bill Anderson warned that the company could stop selling Roundup in the U.S. if the lawsuits are not resolved soon. Anderson said last May during an event hosted by American media group Axios that the herbicide was “essential” in the fight against global food insecurity.

He recently applauded Trump’s policy shift, adding, “The stakes couldn’t be higher as the misapplication of federal law threatens the availability of innovative tools for farmers and investment in the American economy as a whole.”

The Supreme Court could limit future lawsuits

It is now up to the US Supreme Court justices to decide whether to grant Bayer’s request. If this is the case, a judgment is expected to decide in mid-2026 whether the German company will receive comprehensive legal protection.

A positive ruling could save the company billions of dollars in pending litigation. In addition, it could become more difficult in the future for consumers to make claims for harmful products and to drastically limit claims for damages.

Whatever the outcome, Chris Hilson, a professor of law and climate change at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, warned that the Roundup-related lawsuits could be “just the beginning” of a broader wave of litigation against the agri-food sector.

“So far, climate disputes have focused primarily on the energy transition, with fossil fuel companies in the crosshairs,” Hilson told DW. “We can expect more litigation driven by the environmental movement, both on climate grounds and on biodiversity and human health grounds.”

Europe is closely following the Bayer case in the US, as the European Union has extended the use of glyphosate until 2033 despite strong opposition from environmental groups. Some EU member states, including France and Austria, continue to push for stricter limits or outright bans.

(OS/CHP)