A few days ago, the Network of Authorities of Scientific and Technical Institutes (Raicyt) reported that “Thursday, December 4, 2025, will unfortunately remain in history as a key date for the dismantling of the Argentine scientific system,” announced the organization that brings together more than 400 directors of scientific organizations. The statement came about because the R&D&I Agency, which is under the Ministry of Innovation, Science and Technology, canceled the already awarded tenders for PICT 2022 research projects and permanently closed the 2023 tender. What happened is consistent with President Milei’s statements that he refused to fund scientific research in Argentina and even went so far as to claim that it should be privatized, as if it were something alien to state policy.

Defunding science is not just an administrative adjustment; It is a strategic amputation that determines the economic, social and technological future of a country. When a government dismantles or dismantles its scientific institutions, it consciously gives up the ability to generate its own knowledge, train a highly skilled workforce, and develop technologies that enable independence, industrial development, and sovereignty.

Authoritarians don’t like that

The practice of professional and critical journalism is a mainstay of democracy. That is why it bothers those who believe that they are the owners of the truth.

The intention expressed by Javier Milei to “privatize” science or to transform research into an activity exclusively driven by the market reveals a profound misunderstanding of how the scientific system works worldwide and ignorance of its importance for each country. No scientific power—not the United States, not Germany, not Japan, not South Korea, not China—delegates basic and strategic science into private hands. The private sector invests when there are clear and predictable benefits, but the discoveries that go on to revolutionize entire industries almost always arise from long-term, uncertain and costly projects with no immediate return: exactly the kind of investment that the market never accepts on its own. Mariana Mazzucato, a leading American economist and professor at University College London and the University of Sussex, in her book The entrepreneurial state. Myths of the public sector versus the private sectorhas destroyed the idea that only private capital produces innovations in scientific matters, but public investments always produce innovations that can then be developed by private companies.

Argentine science and technology at risk of extinction

Public science develops breakthrough vaccines, satellite technologies, genetics, new energies, innovative materials and complex data platforms. Public science enables the existence of the innovative private sector and not the other way around. All the new drugs that have been developed for use in the different types of cancer have been developed thanks to public investments and in Argentina there is enough evidence of this.

What is at risk in Argentina

Despite cyclical crises, Argentina has built a scientific system at the highest level in Latin America for decades. CONICET has been ranked among the best organizations in the world; Its institutes trained professionals in critical areas such as biotechnology, physics, astrophysics, chemical engineering, marine sciences, nuclear energy, translational medicine and social sciences. There are many achievements of our scientists and researchers that we can mention

- The vaccine against Argentine hemorrhagic feverdeveloped by the Maiztegui Institute, unique in the world.

- Satellite development (ARSAT, SAC-D, SAOCOM), with crucial contributions from CONAE and national universities.

- Agricultural biotechnologywith research that made it possible to transform agriculture, increase yields and promote the export of knowledge.

- nuclear developmentwith export reactors (NA-SA and INVAP), one of the most modern capacities in the country.

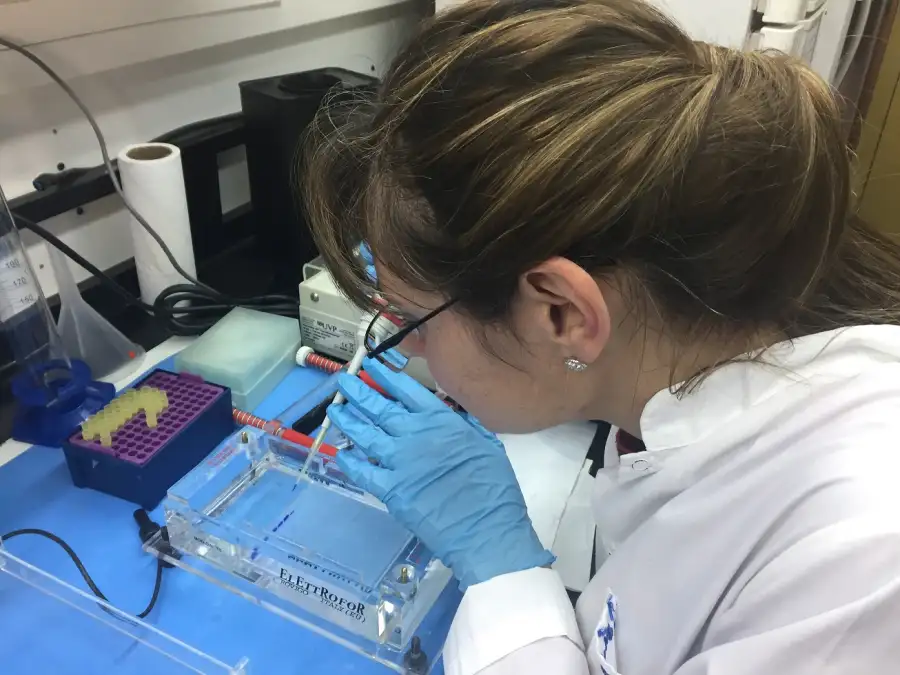

- The creation of diagnostic kitsmedical excellence research and laboratories that have been essential for analyzing samples, producing supplies and modeling data during the pandemic.

- Argentine astronomywith groups participating in global projects such as Pierre Auger and collaborating with high-level observatories.

- Social sciences: In the field of social sciences, there is notable work in history, sociology, and philosophy coming from government-funded researchers.

This scientific framework was not created overnight. It is the result of generations of researchers, scholars, technicians, public universities, state institutes and sustainable policies who, despite all the ups and downs, have understood that without science there is no modern nation. I know all too well the costs associated with research and the hard work that must be done, even if the results are not immediately visible. In my personal case, I have been able to owe all the research work on economic history and other subjects on which I have published and which can be found in the most important libraries in the world to the public institutions that have provided me with tools to carry out the work.

The privatization of science: a conceptual and strategic mistake

Privatizing science is not only unfeasible; It’s a contradiction in terms. Basic research – that which enables future discoveries – does not bring immediate profits. It requires government, stable funding, decades of planning and freedom to explore. If a country forgoes financing this structure, it condemns itself as a consumer of foreign technologies and is dependent on decisions made outside its borders.

Furthermore, the idea that the market will replace the state ignores that companies will only innovate when there is a strong public scientific ecosystem to act as a base. Without decades of investment by the American government in physics, mathematics, electronics and computer science, Silicon Valley would not exist. Without universities that generate new molecules and fundamental knowledge, pharmaceutical companies would not exist. The private aerospace industry thrives on government contracts.

Defunding Argentine science does not lead to efficiency, but to backwardness. And its privatization does not liberate the state, but rather makes it dependent.

The most serious loss: human capital

When science adapts, the first to go are the young scientists. They emigrate, they look for stability, functioning laboratories, decent salaries and projects that are not dependent on the political climate. This flight is not only a personal loss, but also an economic loss. Training a doctor in physics, biology or materials engineering requires years of public investment. When they leave the country, the investment is transferred to another country for free.

A state that destroys its own scientific capabilities transfers talent, knowledge and competitiveness to others. It is the quietest but most profound form of deindustrialization.

We cannot forego the future

Science is not an expense. It is a condition of possibility: without science there is no industry, without industry there is no quality employment, without employment there is no development and without development there is no sovereignty, and without sovereignty there is no true independence but a fiction that determines the future of a nation.

Its definition is an act of political improvisation that endangers multiple generations.

Argentina has irrefutably proven that it can produce outstanding science. The question is whether it wants to continue like this or whether it will resign itself to being a dependent country, a buyer of technology, a distributor of talent and a passive observer of other people’s progress. Resigning oneself to using only the science and technology produced by others is the most tangible evidence that one has not the slightest idea of what a state policy is, and that one only wants to force the nation to be a kind of caboose for countries that have a future because they have science, and, moreover, they do not function solely on the amalgamation of their deficits and are not bound by rigid tax orthodoxies that prevent the financing of that future.

The Nobel Prizes that Argentina received were won by men and women trained in public institutions, at a time when publicity was still a national priority. We were not subject to the mediocre economists who reduce everything to immediate utility and who, even when guided by the same narrow criteria they claim to defend, have demonstrated time and again their ineptitude and failure. This contrast shows something obvious: when a country chooses knowledge, it advances; If it is given over to the logic of permanent adaptation, it will regress without any remedy.