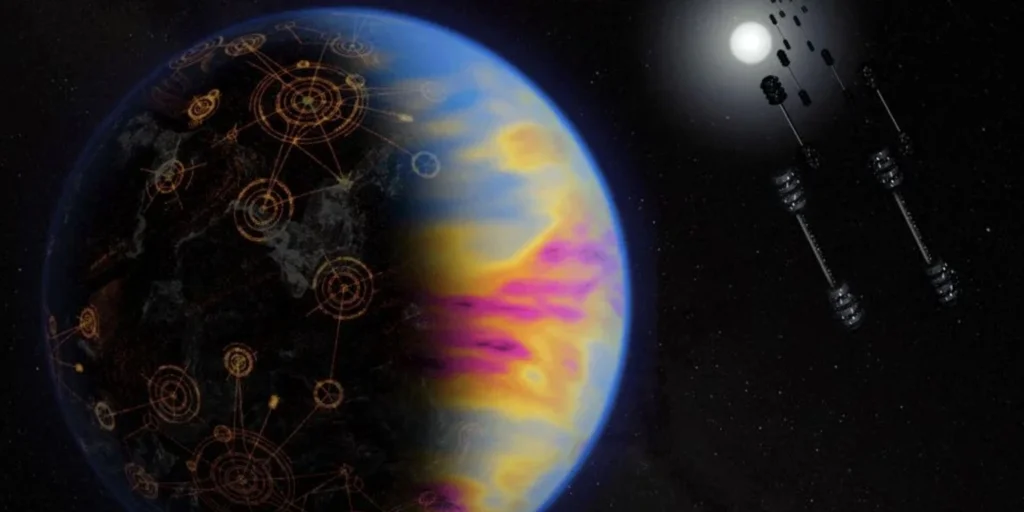

Our first contact will not be with a prosperous and peaceful civilization. Nor will it look like what science fiction writers imagined, who did everything possible to prepare us for possible contact with extraterrestrials. Invasions of hostile species, huge ships … who threaten our cities, contacts with highly evolved species, benevolent extraterrestrials who have come to save us from ourselves… None of that.

The first civilization we detect won’t necessarily be very advanced or conquering, according to a new study by famed astronomer David Kipping of Columbia University. Although it will almost certainly be a “noisy”, unstable civilization and, most likely, plunged into its own final agony.

Under the title The Eschatian Hypothesis, the work will soon be published in “Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, although it is already available on the preprint server “arXiv”.

Kipping, director of the Cool Worlds laboratory at Columbia and a successful popularizer, starts from a postulate that astronomers know well, even if the public often ignores it: in space, the first thing we see is never the “normal”, but rather the most extreme.

A sustainable and peaceful civilization would be practically invisible to us; whoever detonates nuclear weapons or burns its atmosphere emits an unequivocal signal

The history of astronomy, in fact, is littered with “first detections” that turned out to be very rare exceptions, not the norm. This is called “observation bias.” If we walk into a dark room full of people whispering and there is a single person screaming at the top of their lungs. Who will we detect first? Obviously, to the one who shouts. But that doesn’t mean everyone in the room is screaming, it means that screaming is the only “signal” loud enough to stand out from the rest.

Rare and extreme cases

“The history of astronomical discoveries,” Kipping explains in his study, “shows that many of the most detectable phenomena, especially early detections, are not typical members of their class, but rather rare and extreme cases, with disproportionate observational signatures.”

When we look at the night sky with the naked eye, for example, we can see about 2,500 stars. And about a third of them are giants, huge, bright stars. Therefore, if we only relied on our eyes, we would think that the Universe is full of giants. But it’s a lie. In reality, these stars are a minority, less than 1% of the total. What happens is that they are so bright that they “jump” into our view, while the red dwarfs, our closest neighbors, which constitute the true majority of the galaxy’s inhabitants (about 80% of the total), remain invisible to the human eye due to their dimness.

The search for exoplanets tells us the same story. In the early 1990s, long before the discovery of other worlds became routine, the first planets outside the solar system were discovered in the most inhospitable place imaginable: orbiting a pulsar, the spinning corpse of a dead star, a cosmic “beacon” that, as it rotates, emits radiation with clockwork precision. In other words, the planets orbiting the PSR B1257+12 pulsar were not detected because they were common, but because they slightly modified the perfect rhythm of the “pulsations”.

Today, with more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, we know that such worlds are in fact absolutely rare. In fact, only about a dozen similar planets have been discovered.

And now, in his study, Kipping applies the same logic to the search for aliens. “If history is any guide,” he writes, “it may be that the first signatures of extraterrestrial intelligence we detect are also very atypical and ‘noisy’ examples of a broader class.”

The scream hypothesis

This is where the term that gives its name to the study comes in: “Eschatological”. The word comes from “eschatology”, the part of theology and philosophy which studies the final destiny of the human being and the Universe (from the Greek “escatos”, last), that is to say death and the final judgment. Not to be confused with the similar term “skatós”, which means excrement and which gave rise to the same word also referring to physiology and vulgar language.

Well, Kipping proposes that technological civilizations, like stars, could experience multiple phases. And the brighter phases, those that emit more energy (and more signals into space), are also generally the least stable. Consider a supernova: it is the brightest and easiest to detect event in a galaxy, visible millions of light years away, but it represents the violent death of a star, not its usual state.

It is no longer a question of looking for stable signals, of listening for hours, but rather of constantly monitoring the entire sky, looking for flashes, anomalies that barely last days or weeks.

“Motivated by this,” said Kipping, “we propose the eschatological hypothesis: that the first confirmed detection of an extraterrestrial technological civilization is most likely an atypical example, unusually ‘noisy’ (i.e., one that produces an unusually strong technosignature), and plausibly in a transient, unstable, or even terminal phase.”

In practice, this means that a quiet, sustainable, ecological civilization, living in balance with its planet for millions of years, is likely to be “quiet” in terms of radio emissions or energy. We won’t see it. On the other hand, a civilization that burns through its resources, detonates nuclear weapons on a global scale, or desperately modifies its star to survive, will emit a very powerful signal.

Some scientists had previously suggested that our own civilization might be entering this “noisy” phase. Climate change, the accumulation of chemical pollutants in the atmosphere or the radiation from our telecommunications could be perceived from the outside as the “fever” of a sick society. In Kipping’s words, “a byproduct of a declining civilization.”

Was the “Wow” signal a cry for help?

The hypothesis even allows us to speculate about mysterious signs from the past. Kipping wonders, for example, about the famous “Wow! signal. detected in 1977, a unique and very powerful radio burst which has never been repeated. Under the prism of the eschatological hypothesis, it was perhaps not a greeting, but a final cry for help. It could have been, as the author suggests, “the very loud cry for help of a civilization approaching its own end”.

For Kipping, it is logical to think that if a society feels, or knows, that it is going to disappear, or if it enters into a violent energetic collapse, this short period of time will be the one that leaves the biggest mark on the electromagnetic spectrum. According to the astronomer’s simulations, if a society is “noisy” for only one millionth of its life, it must emit an immense amount of energy at that “instant” for us to have a chance of seeing it before its “silent sisters”.

A new research strategy

The new study, according to Kipping, implies that it is quite possible that until now we have been looking for “evil.” Much of SETI’s efforts have always focused on finding continuous signals, persistent beacons, or repetitive messages to anyone who can hear them.

But if we change focus and start looking for “accidents” or brief “bursts” of technological activity, then we will need to change tools. “In practical terms,” advises the astronomer, “the eschatological hypothesis suggests that wide-field, high-rate studies optimized for generic transients may offer our best opportunity.”

That is to say, it would no longer be a matter of pointing at a star and listening for hours, but rather of constantly monitoring the entire sky, looking for flashes, anomalies that last for days or weeks and then disappear. Kipping points out that we’re entering a “golden age” for this type of research thanks to observatories like the Vera Rubin or the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, which constantly scan the sky for changes, for things that suddenly turn on and off.

“Instead of targeting narrowly defined technosignatures,” the study concludes, “eschatological search strategies would prioritize broad, anomalous transients (…) whose luminosities and timescales are difficult to reconcile with known astrophysical phenomena.”

In short, it is very likely that our first “contact” will not be with an invader, nor with a peaceful “galactic ambassador”, but with the cosmic equivalent of a devastating fire, or a shipwreck: a clear and brief signal from someone who has shone too brightly before going out forever.