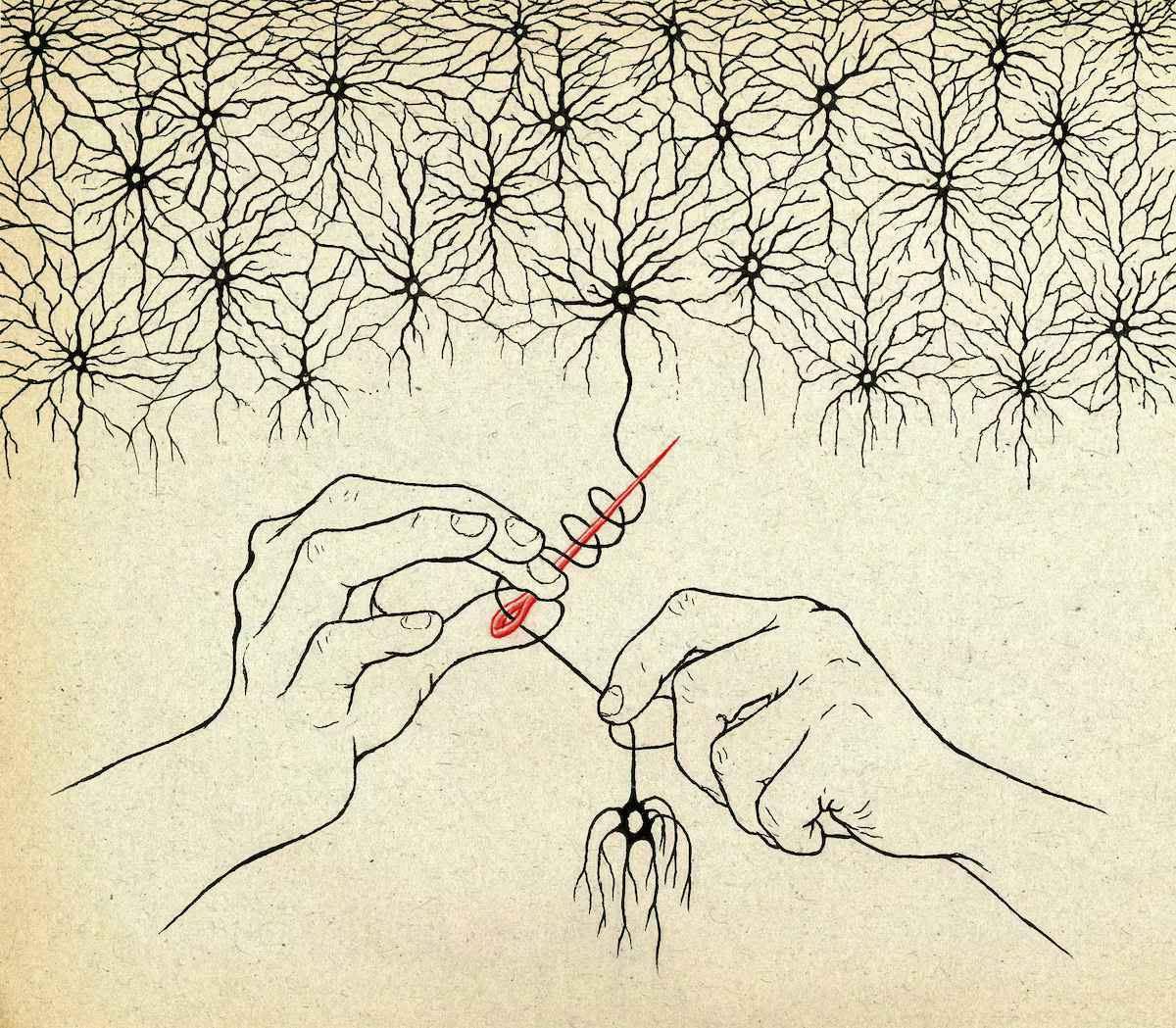

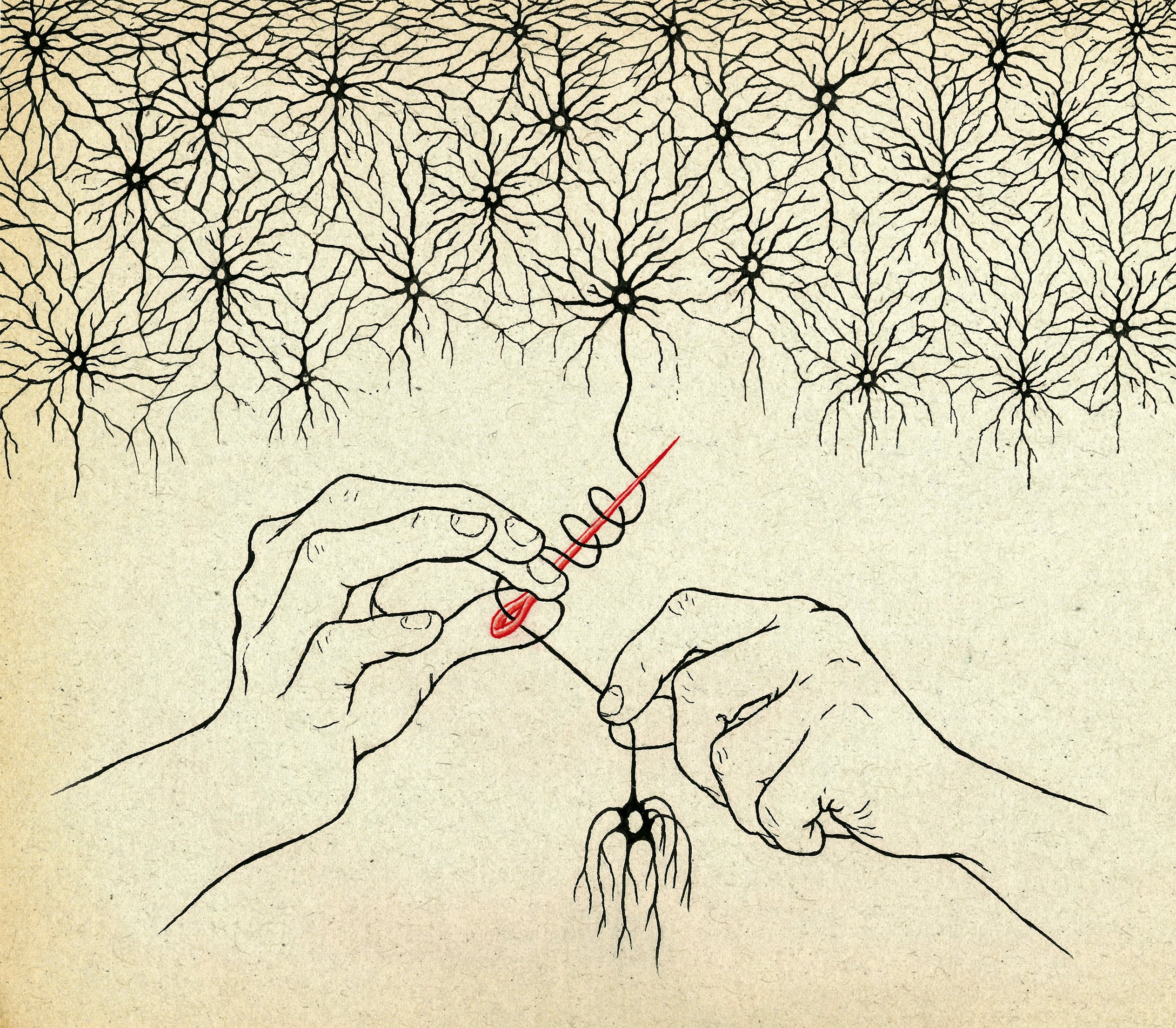

What can a needle tell us about the human brain? And what can embroidery tell us in these turbulent times? During the most uncertain days of the pandemic, when everything was calming down and hands were looking for something to do, a group of people decided to embroider neurons. With thread, needle and patience, they reinterpreted the drawings of the Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal, as if each point revealed a secret of the brain. This is how the Cajal Embroidery Project was born, an initiative that connects science and art, in which each embroidery is also a way of thinking and resisting. Faced with a reality that has become disjointed, the subtlety of embroidery has revealed itself as an effective means of confronting the turmoil of the human spirit.

The project, designed to commemorate the centenary of the Cajal Institute in Madrid, was going to be presented at the Congress of the European Federation of Neuroscience Societies, in Glasgow, in 2020. But the pandemic forced it to be reinvented. The idea arose during a conversation between two Edinburgh neuroscientists: Jane Haley was considering showing Cajal’s original drawings in an exhibition, but, encouraged by Catherine Abbott’s suggestion, she ended up coordinating an embroidery project. The lockdown transformed it into a remote experience. The title of Nancy Huston’s novel Slow emergencies (slow emergencies) can be a perfect description. Embroidering neurons was not just a manual activity, but a form of intangible support that managed to slow down the fracture. As if each point could connect the synapses themselves. As one of the project participants said: “There is something about connecting with your hands that allows your mind to clear.” »

Cajal clearly felt this: “Each human being, if he thinks about it, can be the sculptor of his own brain. » Like other craft practices, embroidery simultaneously activates motor, sensory, visual and linguistic areas, and stimulates hand-eye coordination, sustained attention and pattern memory. Concentrating on a manual task momentarily disconnects us from our thoughts: we cease to be the weight of our daily life and it is the materials – thread, fabric, wood, clay – that begin to shape us. Everything happens as if, by working with our hands, we dematerialize ourselves to reintegrate a network of meaning. In difficult times, such as confinement, neural connections, links, resilience and plasticity were created thanks to this collective gesture. And this is where the paradox arises: in emergency situations, we need time to devote ourselves to slow, contemplative practices, like embroidery, which promote mindfulness. Embroidery offers another temporality which does not compete with that of the clock.

According to psychoanalysis, this could be understood as a form of reparation. Freud spoke of the “work of mourning” as a repetitive, almost artisanal process. Her daughter Anna knitted while listening to her patients, to allow freer listening. In mythology, Penelope embodies this active waiting: every night, she weaves and unweaves the shroud of Laertes. His gesture is not passive, but rather his way of resisting the passing of time and keeping alive the possibility of reunion with Ulysses. Embroidery is not just about decoration, but also about storytelling, elaboration and maintenance. Perhaps in these times of global uncertainty, embroidery involves not only neural connection, but also a way of rethinking the structure of the world.

In Chile, under the Pinochet dictatorship, arpilleristas – women who had lost their loved ones and their livelihoods and who also had no right to work – turned domestic sewing into a political and therapeutic language. Driven by their collective memory and the traumas they experienced, they embroidered scenes of disappearance and denunciation in clandestine workshops. As Violeta Morales, mother of missing Newton, says: “We wanted to embroider and express our pain, but also convey a message of resistance. » Each stitch was a heartbreak, a memory and a resilience. The thread and needle can not only connect neurons, but also suture wounds, reconstruct connections and weave memories.

This tactile and attentive relationship produces a presence that promotes sustained states of concentration in which the flow of time slows and the mind calms. Sociologist Richard Sennett argues that craft is not just technical work, but embodied thought: the connection between the hand and the materials of work generates a type of profound and transformative knowledge. Sennett mentions Kant, who more than two centuries ago casually remarked that “the hand is the window to the soul,” an observation that condenses the evolving dialogue between our hands and the psyche.