Sometimes a book begins with a phrase heard in passing, an idea caught on the fly. This is what happened to Carlos Arenas (Seville, 1949), retired professor from the Department of History and Economic Institutions of Seville, when he heard Esperanza Aguirre on a television news talking about “mamadurrias”, to designate public subsidies. This was not the only case; Other politicians have scornfully called this aid a “reward,” viewing its recipients as mere parasites of the “daddy-state” and burdens on economic development. There, Arenas thought, was a subject to study.

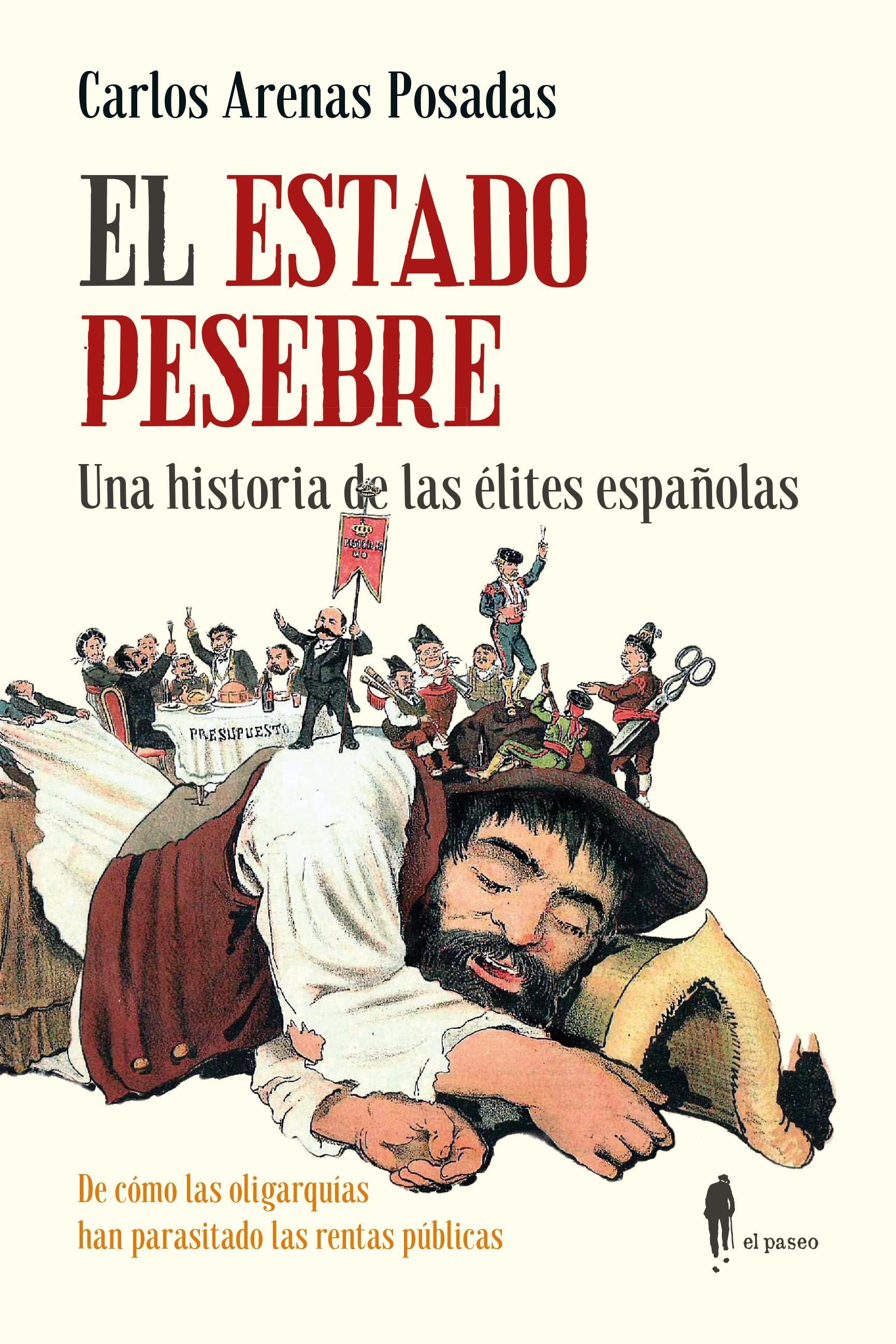

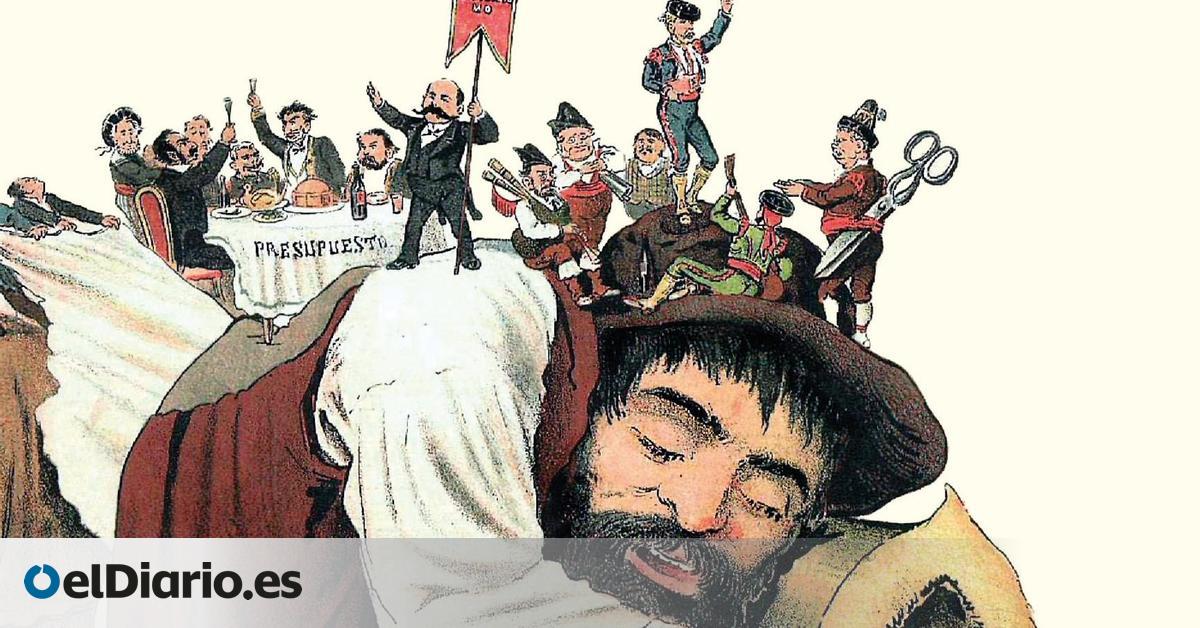

“I set out to study, with a lot of data, the capitalized Mamandurrias that the oligarchies have had in Spain since the creation of the State, at the end of the Middle Ages, until the present day. The thousand forms, methods and fraudulent acts perpetrated with the connivance of mental and cultural trompe-l’oeil that try to lull people or deceive them.” The result is The Manger State (El Paseo Editorial), a detailed review of the historical plundering of public coffers by these privileged groups.

“Since ancient times, the elites have taken the State as a manger and obtained its benefits, privileges, etc. », Comments the author. “We could go back very far, but among the most striking, I would highlight the fact that the Austrians and Bourbons, in the 17th and 18th centuries, sold positions and titles of nobility, because they needed money for their wars. And whoever bought the title or position, obtained the return, in addition to honor and prosapia. The return came from the theft from the people, hand in hand, of the institutions they occupied. In today’s democracy, positions are not sold much, but politicians are, as we see, as well as judges. It is an indirect, but equally effective, way for the elites to continue to occupy the State.

Another striking case, adds Arenas, is that of the famous cliques of the 19th century, “like those of María Cristina, the wife of Ferdinand VII, or Isabella II. Not only were there absolutely fundamentalist nuns or priests, but there were oligarchs like Salamanca, swordsmen like Narváez, who did, let’s say, real business at the cost of being very, very close to the kings.” “We could also remember Alfonso “The oligarchies will accumulate capital. And then, already in the Transition, we know the pressure groups, the lobbies, the revolving doors… Everything is the same.”

latent civil war

Arenas does not hesitate to point out that these practices still persist today: “The same church continues to agitate with its charter schools and its private universities. At the moment, ‘the Chirons,’ right? Who are the Chirons? Well, more of the same thing, another drop, another element of something that comes from very old. They are not isolated rascals, they are not bad apples. This is the system.” he says. “The book ends on May 25, but I wish it had ended today. I would have told the story of the chyrons and housing and masks and all that kind of stuff. We have an economy, a capitalism that we can call rent-seeking, where whoever has the most political power takes most of it.

Even justice does not escape the historian’s magnifying glass. “We already see how the sentences that should set an example are pronounced by certain gentlemen who are not at all exemplary, who only seek to divide Spanish society in two, in a plan for civil war: those who believe that the Attorney General was well condemned and those who say that they were badly condemned. I believe that in Spain it is not necessary to win wars. It is enough that there is war, that there is a conflict. And this sentence, like so many others, seems to be going in this direction a kind of latent civil war to scare people so that they do not take political action on the matter.

On the other hand, it is not always a question of putting your hand in everyone’s pocket: often, the crèche comes from tax evasion. “We also need a little culture of solidarity and redistribution of taxes. The poor pay, but I save it,” laments Arenas. “Those who vote for Vox and those who vote for the PP are generally people who say why they are going to pay taxes, because they are going to Sánchez. Well, if they don’t want to pay taxes, don’t let them benefit from it: health will be universal, especially for you who don’t pay taxes; for the toughest. A little political behaviorism wouldn’t hurt. »

Enemies saved

What also draws attention throughout the book is the way in which these lootings are systematically whitewashed, allowing the thieves to go down in history as great men, saviors of the country, worthy of all honors. “I usually say that the grander the message, the more deceptive the messengers are. Franco is an example. The grander the honor, the country, destiny, the universal, I don’t know how much, God, etc., etc., the more they get along.”

And the same can be said of the capacity of parasites to always be others. “There has always been an enemy to blame: the Moor, the Jew, the enlightened, the liberal, the republican, the separatist, the social-communist, the anarchist… The enemy is always the other. And we must use physical, moral, cultural violence, whatever, to crush him like a cockroach. We are a country of soldiers and religious people, everything else is the enemy.”

As I have pointed out before, there have been historic opportunities for things to be different. “At the beginning of the 19th century, with the war of independence of the Cortes of Cádiz, there was an egalitarian program which was aborted. And the federalist proposals of the Andalusians were also aborted, between 1820 and 1873. The first republic was an Andalusian republic, because in Andalusia the Federal Republican Party was voted massively. This was aborted in Pavia, as the Second Republic aborted, although this “She made big mistakes. She did not realize that by abandoning Andalusia to its fate, she was abandoning herself. »

The antidote to the “resilient”

“An opportunity was also lost with the Transition, which made people believe that change was happening, and what happened was this kind of decaffeinated, oligarchic democracy that we have, in the hands of the regulars. Therefore, there were times when, either through violence or in a seductive and deceptive way, by deceiving people, the changes were prevented. But I believe that the time has come, finally, to put an end to the resilience of the elites, and that people are now acting on the I am optimistic, I remember Aznar’s phrase: “He who can do, let him do”, but vice versa, each in his field, one writing books, another doing journalism, another doing politics and another doing neighborhood life, we are doing it to put an end to the resilient.

Indeed, even if the panorama described in the volume is rather dark, the ending indicates possible solutions to this age-old evil. “Participate in politics, don’t be fooled by propaganda, and accumulate political capital,” Arenas instructs. “The poorer the people, the fewer voices there are, that is, they are so numb and so beaten that they do not participate or protect themselves from these oligarchies. After the pandemic there was a lot of talk about resilience, but oligarchies have been resilient since the 15th century. Why? Because there have been moments in the history of Spain where it has been possible to turn the situation around. For example, perhaps with the two Republics, or during the Transition And yet, the oligarchies “They were able to recover and stay in power. Then, what we must try is not to be resilient once and for all, and this is done with more democracy, with more transparency, with fewer pacts, by being a little more courageous.”