Once inside the Museum of Almería and approaching the exhibition ‘Reflections. Picasso x Barceló’, it is difficult to ignore one of the most effective museographic resources of this institution: an impressive “stratigraphic column” (a free-standing parallelepiped) 13 meters high. … which dominates the central space and the stairwell of this establishment.

This is formed through strata of earth and archaeological replicas, from bedrock to today, visualizing local societies, such as those of Los Millares (3,200 BC) and El Argar (2,200-1,500 BC), as well as Rome or Al-Andalus. In a visual scan, from bottom to top, the archaeological period up to the present day is shown, which would crown the rectangular and elongated volume.

Already located in the exhibition in question, enveloped in a scenographic and intimate atmosphere, this volume now seems to become, horizontallyin the axis which articulates the whole: a huge base of around 16 meters. A sort of game is made there from 42 ceramic pieces by Picasso (1881-1973), Miquel Barceló (Felanitx, 1957) and the collection of the Almería Museum, which provides 20 references out of the hundred on display.

between the jewels

This museum has some of the oldest ceramics preserved in our country, such as the Neolithic vase found in El Ejido, which is 7,500 years old. In this horizontal parallelepiped, in this central spine around which we gravitate with enjoyment and curiosity, the strata have disappeared, without chronological organization, for example. The strata are not there, but the earth is of each of them transformed into ceramic.

This is part of the happy proposition – perhaps a game – that the curatorial team has imagined. The ceramic pieces are arranged in a certain order (typologies, anthropomorphic echoes or zoomorphic references), linked to each other and breaking chronological stories, so that we can appreciate, at different levels (morphological, technical, iconographic, decorative or finishes such as enameled and burnished), continuities and developments.

Thus, walking around the pedestal is a real treat for the senses and a learning experience that arouses astonishment and surprise, because it is an invitation to discover the authorship of the works, which can be confused, notably between Picasso and Barceló. Wondering about the condition and date of some, like a fragment of a Picasso piñata from 1950, which could pass for an archaeological vestige; or observe the dialogues, quotes and transformations that take place over the 8 millennia of pottery creation that rests on this infinite table.

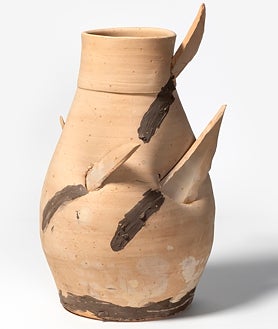

In the images, from top to bottom, Plate decorated with a goat’s head, by Picasso; and two pieces by Barceló: “Untitled”, ceramic from 2021, and “Ganivetades” (2009)

On either side of this journey towards the history of ceramics, in dialogue with this rich ensemble (Neolithic, Metal Age, Greece and Rome and Al-Andalus), are Majorcan masks and other pieces from Malaga accompanied by drawings, reinforcing some of the convergences between the two (bullfighting, reliefs, the African factor).

The climax of the game appears in the final room, a diorama, composed of forty other pieces, which seem to reproduce a nativity scene or a Nativity scene. In any case, it is a ritual procession, like those which took place in Antiquity in honor of Apollo or Theseus, in which figurines of animals and characters are arranged which, probably, “embodied” deities. In this heterogeneous procession, created especially for the occasion, which heads towards a cave portal reminiscent of Barceló’s large ceramic installations, different eras come together again, from Prehistory to the recent details of the Mallorcan project for the Sagrada Familia, including Greco-Roman or Picasso pieces, some with a clear mythological inspiration. We must think that Picasso arrived at ceramics in 1945, with his return to the Mediterranean and the evocation of the original.

The whole allows us to appreciate the performative component of ceramics, which so often preserves the imprint, literally the imprint, of the person who creates it, of their gesture. Into this lies the dimension of experimentation, play and imagination that we find in Picasso and Barceló, as well as the subversion of the practical character of this discipline. The case of Majorcan is paradigmatic, since brought clay work to an undeniable performative condition and scenic through the actions. In many of his works, he transforms, to the point of metamorphosis, amphoras or jugs, which become other realities.

It therefore follows in the wake and teaching of Picasso, who varied the morphology of traditional typologies. In fact, one of Picasso’s key concepts is that of metamorphosis, which occupies the twenties and thirties. Its exposed pigeons allow us to visualize how an imaginative action transforms a container in one of the animals most linked to his biography.

These overflowing ‘Reflections’. Picasso x Barceló’ It has many other virtues. It is priceless, in an Almería whose symbol is the anthropomorphic Sun of Portocarrero (16th century), to see how a bowl with soliform motifs from the Copper Age (3,200-2,200 BC) dialogues with Picasso’s “Vase with Three Heads” and a plate decorated schematically with human features, both from the 1950s.

‘Strengths. Picasso x Barceló’

Almeria Museum. Almeria. Carretera de Ronda, 91. Commissioners: Miguel López-Remiro, Tania Fábrega and Laura Esparragosa. Until March 15. Cadiz Museum. From March 25 to June 28. Four stars.

On the occasion of the centenary of Ortega’s “The Dehumanization of Art”, we remember his judgment in the face of the “suspicious sympathy towards the most distant art in time and space, the prehistoric and wild exoticism” that he found in new art, understanding it as typical of a “fury of plastic geometry” which periodically runs through History. Leaving and returning to the “stratigraphic column”, we cannot avoid placing Picasso and Barceló there, at the top, heirs and renewers of a millennial constant and tons of mud “under their feet”.