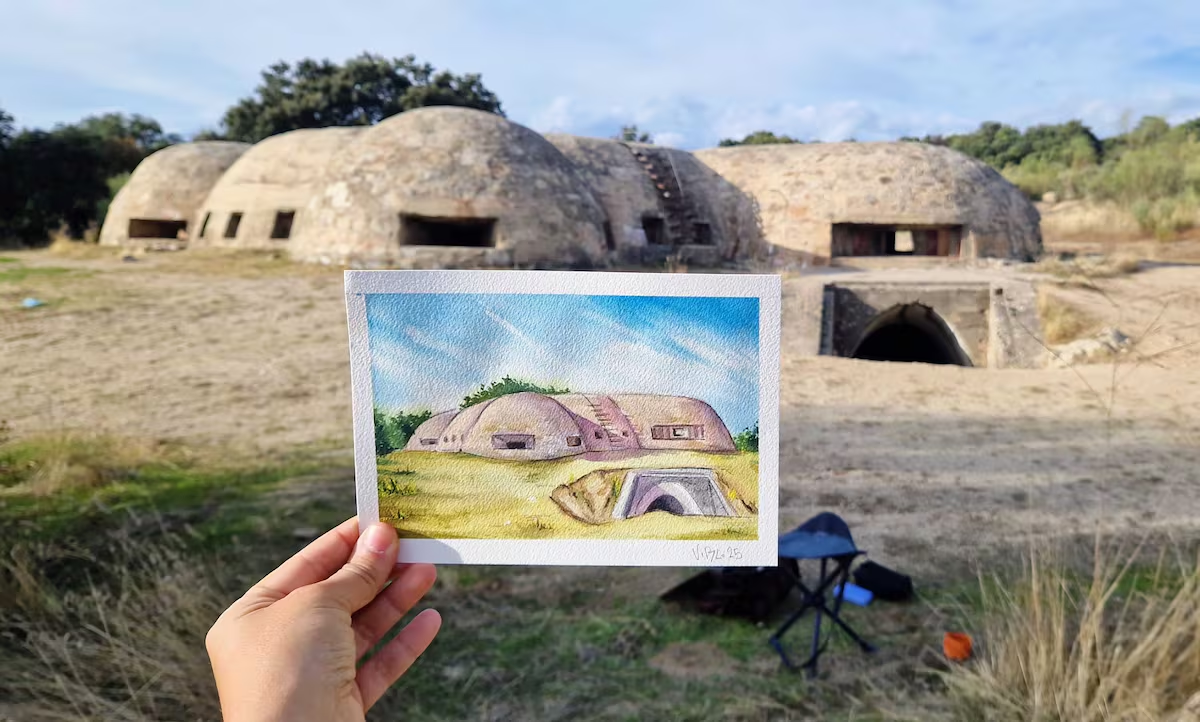

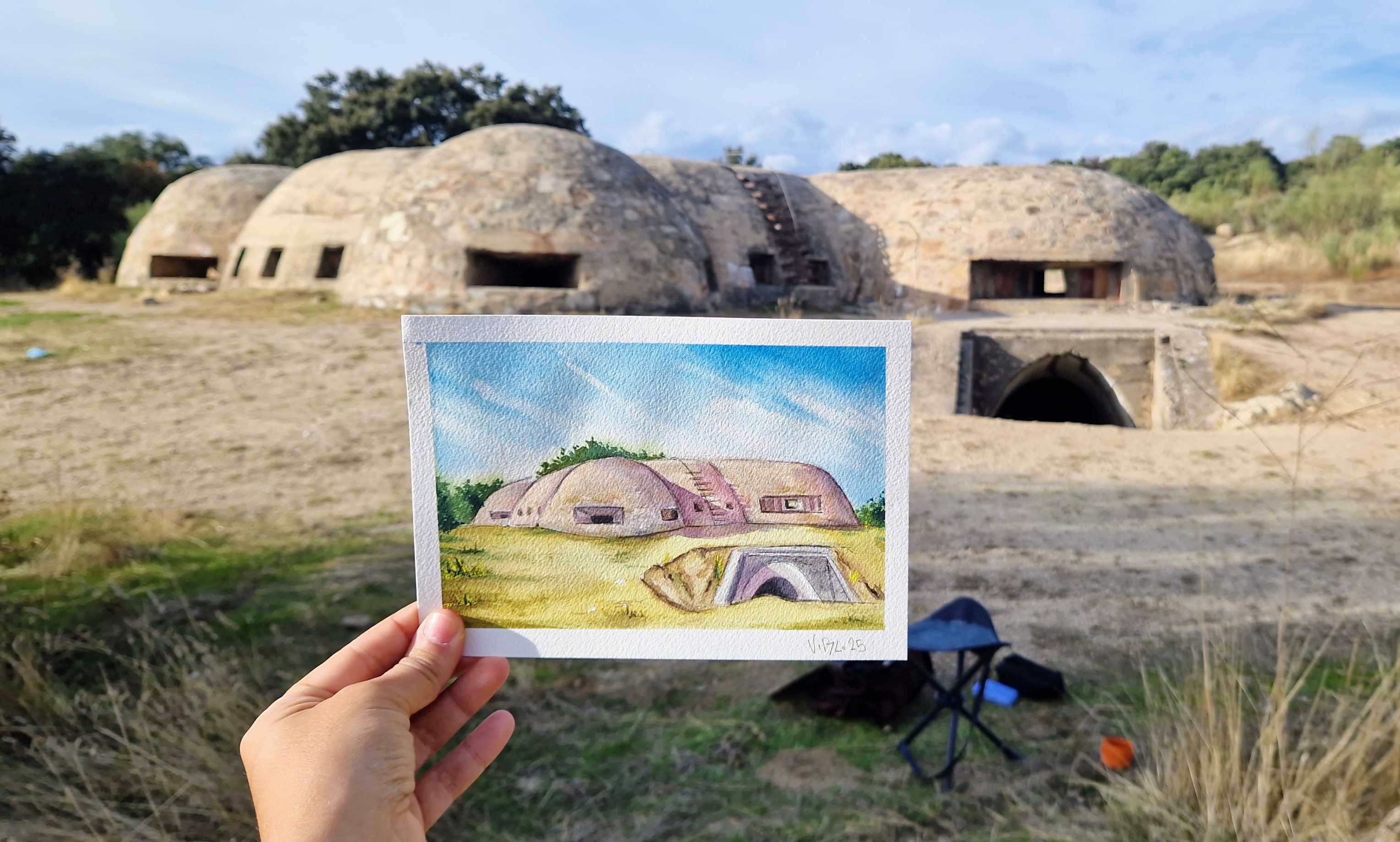

Seven children made Blockhaus 13, in Colmenar del Arroyo (Madrid), the scene of their games. Some throw balls against its concrete walls and others run madly through its tunnels, buying every ticket to get out of there with a gap. At the top of the bunker, two adults, who appear to be the parents of some minors and the temporary guardians of the others, are eating. They leave their position when one of the children falls on his face, starts crying and takes at least five minutes to get up, which is quite common. They check that there is no need to go to the hospital and return to the heights. Perhaps the children think this mass of concrete is a playground because there are no signs indicating that it is actually a Civil War bunker, declared an Asset of Cultural Interest (BIC) in 2019.

“There’s no sign?” Archaeologist Pablo Schnell is surprised. “Before, there were explanatory signs. Not anymore? They’re not always there? Maybe someone took them.” This fort, according to the expert, was full of dirt and covered in graffiti, but it was renovated in 2013. It was cleaned, gutted and properly marked. More than a decade later, it still bears no traces of graffiti and is in relatively good condition, although its tunnels show signs of damp. But what there is no trace of are the information panels. It remains nameless and without history for anyone wishing to visit it. “Based on the condition of the Civil War fortifications, I think they are some of the cleanest and most visitable, but of course these things require maintenance,” Schnell adds.

Blockhaus 13 was built by the rebels in 1938 and was the culmination of a change in the way the fronts were defended. This mass of concrete was not placed on the front line, but at the rear, with the idea that if the Republican side broke the front, it would find defense at road junctions and therefore would not be able to advance along them. “The Republic had demonstrated in the fall of 1938 that it still had an offensive capacity. The mission of this fortification was therefore, if the front fell, to gather a few retreating men, put them there, lock the bolt and become strong as long as they could resist,” explains the archaeologist. Additionally, the upper central part was prepared to accommodate an anti-aircraft gun.

It was first proposed to build a defensive line of 22 bunkers in this area, which remained at 16, but work only began on nine and Blockhouse 13 was the only one to be completed. “Plans are always more ambitious than reality. These forts were very expensive, very complicated to build. And they required a lot of personnel and a lot of equipment,” says Schnell. It was never used as it was virtually finished by the end of the war. It was time to build a double bunker not far from there: “But for now, there is nothing left because there is urbanization and the little that had been built has been destroyed. »

It is generally not common for this type of construction to be preserved so completely, Schnell says. “The post-war period was very hard. These fortifications were built with a lot of iron, with a lot of steel. That, in Spain in the 1940s, represented very good money. The state itself took whatever it could, because the materials were very expensive and very necessary at that time.” And why then did Blockhaus 13 survive this looting and remain intact? “It is not normal that it is so well preserved, but the reason is that the iron armor it has is difficult to remove and is not very large. It is such a massive work that it has the metal very deep inside and with rebars that are difficult to extract.”

And this remained practically the same as at the end of the war. However, there is no point in this piece of history remaining intact if its memory disappears for visitors.