The industrial cordons of the big cities, the chimneys, the workers leaving the factories in uniforms, all at once, seem like postcards of a Western world that is no longer, or at least, is in the process of being transformed. Large-scale industry is increasingly concentrated in the east of the planet.

During the twentieth century, in the United States, manufacturing employment was synonymous with upward mobility, especially for those without a college education. The factories provided good wages, stability, union coverage, and opportunities in cities like Pittsburgh – the “Steel City” – or Akron – the “Rubber Capital.” In the seventies, One in four American workers was employed in manufacturing.

“Factory labor is overrated,” according to an article in The Economist today This number has fallen to less than 10%, and only 4% of workers perform tasks directly on the production line. More than half of jobs classified as “industrial” actually correspond to support or professional jobs such as human resources, marketing, design, or engineering. Even countries with strong industrial surpluses such as Germany, Japan and South Korea have seen their share of factory workers shrink. Surprising fact: China eliminated nearly 20 million manufacturing jobs between 2013 and 2020.

In Argentina, the classical industry also lost its place. Although there are still latent brands such as being one of the 32 countries that manufacture cars, the suburbs of Buenos Aires are synonymous with a veritable factory graveyard that began in the 1990s and which has more plots of land every year.

In the United States, this phenomenon It can be viewed as industrial decline, but it can also be seen as synonymous with progress.also. In fact, American factory output today, in real terms, is more than double what it was in the 1980s. American factories produce more than those in Japan, Germany and South Korea combined. If taken as a country, it would constitute the eighth largest economy in the world. Naturally, they are doing so with fewer people: factory employment has declined as a result of automation, digitalization, and structural changes in consumption, which now favor services over goods.

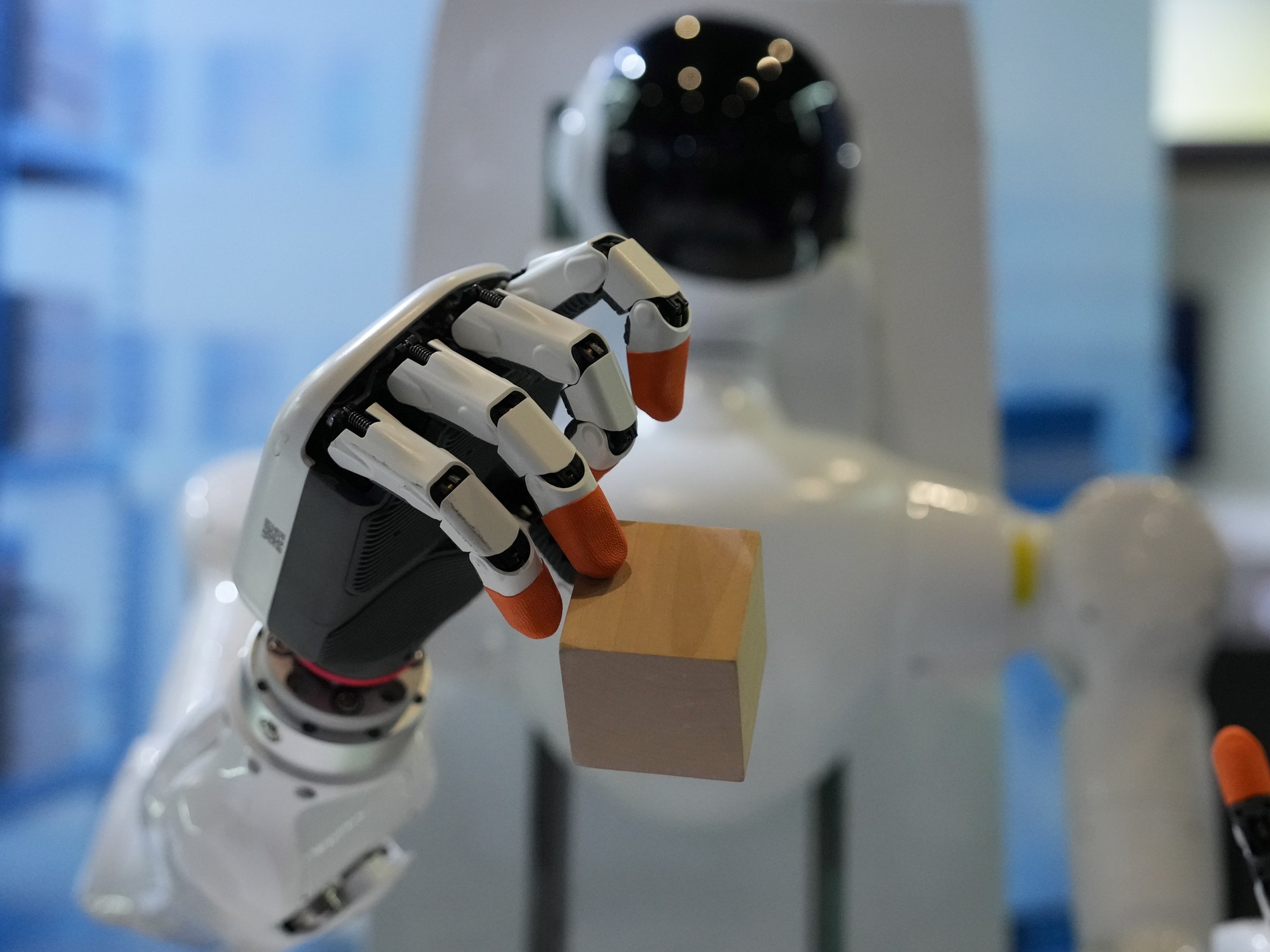

Change has always accompanied business, but its nature is shifting. According to Accenture’s Pulse of Change survey – based on the views of more than 3,000 executives around the world – technology has become the main driver of global business change, with generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) at the forefront. Latin American companies are no exception. In Brazil, for example, CEOs They considered adapting to technological advances a major priority for them in 2024By 2025, technological disruption will be among their top three concerns.

However, nearly half (44%) of these executives admit that they do not feel fully prepared to face these changes. And they’re not alone: workers are also wondering what the future defined by the AI general will look like. In fact, 3 out of 4 in Brazil believe their situation will be significantly affected – or completely transformed – by this technology, making retraining a necessity to either remain competitive in their roles or move into new roles.

However, analyzing the scale of impact that generative AI can have in Latin America has been little explored. According to Accenture, generative AI has huge potential to accelerate value creation across Latin America. However, as with any disruptive technology, His first steps are riddled with uncertainty. Media messages reflect this. After the launch of ChatGPT, concerns about job losses dominated the news headlines. More recently, discussions have focused on data privacy. However, careful analysis can help challenge some prevailing myths. .

Accenture developed three different growth scenarios to compare the impact of different approaches to generative AI adoption: “Aggressive,” “cautious,” and “people-centered.”. These factors take into account key variables such as the pace of adoption, the likelihood of a career transition, the quality of the job, and the potential for displacement.

As the Economist article says, the lesson is clear: The heart of the working class no longer beats in the factories. As happened with agriculture after the Industrial Revolution, manufacturing employment is being displaced by technological and demographic shifts. The challenge is not to rebuild the glorious industrial past, but to improve the quality, productivity and dignity of the jobs that are already growing. This may also mean adopting tools such as artificial intelligence to increase the value of personal and technical services. The question is whether countries like Argentina are investing in order to provide the labor needed for the new industrial revolution.

Argentina knew how to grow with an industrial model that is currently in crisis in the world. At the same time, the current government’s decision does not seem to focus on the industry, at least on the industry that has developed in the country, where a world of small and medium-sized companies has been built, as well as large companies, which today see imports from China and other Asian countries as a real threat. On the other hand, technology-based service companies are beginning to flourish. The best example of this is Mercado Libre, which within a few years has become a transnational company and the largest company in Argentina.

Traditional industry also has arguments to stimulate discussion. The main reason is that even though they call it a subsidized industry, they stress that technology companies have a law that exempts them from some of the taxes they pay.

However, there is still a threat facing both industries. This threat is China. In reality, More and more Argentines are buying imported products and on platforms from that country such as Temu or Shein.