Credit, AFP via Getty Images

-

- author, Navin Singh Khadka

- To roll, Environment Correspondent, BBC World Service

-

Reading time: 8 min

A few years ago, Muhammad Yaqoob Baloch and his family almost abandoned their home in Keti Bandar, southern Pakistan, after rivers and wells dried up.

It became difficult to find water to drink and crops failed on several occasions.

“People from New Delhi, Mumbai and China came to buy our rice, wheat and vegetables,” says Baloch, who is also a farmer. “But more than 50,000 hectares of our land have become unproductive.”

Many residents abandoned land inherited from their families, and Baloch was on the verge of doing the same until the government opened a desalination plant and began producing drinking water from the Arabian Sea.

Today, many of those still living in the area manage to support themselves by farming crabs in the irrigation canals, now filled with salt water, while continuing to farm what they can.

Pakistan is one of several countries around the world that have expanded seawater desalination as global warming makes fresh water increasingly scarce.

Until recently, this practice was largely limited to the rich, arid countries of the Middle East, but global warming has changed this scenario.

According to Global Water Intelligence (GWI), a company that provides market analysis for the water sector, around four in five countries (80%) today produce desalinated seawater for human consumption and other purposes, and this figure is only increasing.

According to the survey, Brazil recorded a 189% increase in the amount of desalinated seawater between 2010 and 2025, reaching 1.4 billion liters per day.

Among the initiatives underway in the country is a factory in Espírito Santo, built by a steel company that uses desalinated water in its industrial process.

Plans are underway to build desalination plants on the São Paulo coast, in Ilhabela and in Ceará’s capital, Fortaleza, both for human consumption of desalinated water.

Faced with negative repercussions among experts and telecommunications companies, the Ceará government changed the location of the project.

In countries like Kuwait, Oman and Saudi Arabia, more than 80% of water supplies now come from desalination, either from seawater or from underground sources of brackish water – that which contains more dissolved salts than fresh water but less than seawater.

During the recent Israeli and American attack on Iranian nuclear facilities, Qatari officials expressed concern about the possibility of contamination of the Gulf, which is now the main source of water for Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait.

Credit, Veolia

Why isn’t there enough fresh water?

Here’s the problem. Nearly two-thirds (67%) of the planet’s surface is covered in water. However, according to the United Nations (UN), only 0.5% of this total is usable fresh water, and even this proportion has been declining rapidly due to rising temperatures and droughts.

In a report published in 2023, the World Commission on Water Conservation warned that there could be a supply gap of 40% by 2030, while the world’s population is expected to reach 9.7 billion in 2050.

Corruption and mismanagement of water resources have also contributed to severe water shortages in many countries.

Given that oceans contain more than 95% of the world’s water, many argue that seawater is a possible solution, even though its share of total global water consumption is still quite limited.

Credit, AFP via Getty Images

Global expansion

Desalination plants have sprung up in more than 20,000 locations around the world, almost double the number recorded a decade ago, studies show.

“The desalination market is expected to accelerate its growth over the next five years, driven mainly by the Middle East and North Africa, Asia-Pacific and some European countries,” says Estelle Brachlianoff, CEO of Veolia, one of the leading international water companies active in the desalination sector.

Data collected by GWI shows that around 160 countries already have desalination plants that treat seawater.

On average, 60% of the water produced is used for public drinking water supply, depending on the entity.

“Desalination is already helping many countries deal with chronic water stress,” says Rachael McDonnell, deputy director general of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), a research organization dedicated to water security.

“While desalination is not a silver bullet for all drought-prone regions, it is already playing a key role in helping many countries strengthen their water security in the face of drought and increased demand. »

GWI estimates that the sector is growing at a rate of more than 10% per year.

According to the organization, over the past 15 years, the production of desalinated drinking water has increased significantly in more than 60 countries, in all regions of the world.

The survey shows that while many saw increases of two, three or even four times — Singapore, for example, grew 467 percent — others saw even more significant expansion, from 10 to 50 times.

Saudi Arabia is the country that produces the most desalinated seawater: 13 billion liters per day, enough to fill 5,200 Olympic swimming pools, according to GWI.

Bangladesh, India and Pakistan use desalination technology not only for seawater, but also to treat brackish water in areas where advancing seas have contaminated groundwater.

Afghanistan uses this technique to desalinate groundwater that is brackish for other reasons.

How does desalination work?

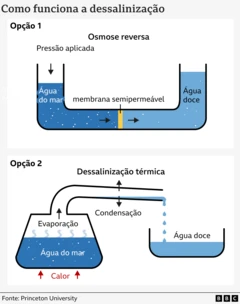

Desalination is mainly done in two ways.

The first, most common and most energy efficient, is reverse osmosis, which involves applying pressure to force water through a semi-permeable membrane, which traps salt and other chemicals.

The second method is thermal desalination. In this process, seawater or brackish water is heated; it then evaporates and the condensed vapor is collected as fresh water.

Cost

Traditionally, desalination has been an expensive technology, but the use of cheaper renewable energy sources and increased efficiency have reduced costs in recent years.

According to experts, the cost of producing desalinated water has fallen by up to 90% since 1970.

IWMI research shows that combining desalination with solar power could make it even more economically viable by 2040 in many coastal areas.

However, a large desalination plant with the capacity to produce 500 million liters of water per day requires an investment of around $500 million (around 2.7 billion reais), according to Veolia.

Another significant cost is transporting desalinated seawater to dry inland regions.

“In developing countries, cost remains a barrier,” says Shakeel Hayat, an expert on climate change, water, sanitation and hygiene at WaterAid, an international organization that has helped create around 100 small desalination plants in South Asia.

“For many of these countries, small solar power plants, intended to transform brackish water into drinking water, are more viable than large seawater desalination projects.”

Credit, Getty Images

The brine problem

One of the biggest challenges of the desalination process is the removal of brine – the highly salt-concentrated water that remains after removing potable water.

The discharge of this brine into the sea increases the salinity and temperature of the water and can seriously affect marine ecosystems, even creating dead zones around the discharge points.

“In most desalination processes, for every liter of drinking water produced, approximately 1.5 liters of liquid polluted with chlorine and copper are generated,” said the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

“If not properly diluted and dispersed, these discharges can form a dense plume of toxic brine, capable of degrading coastal and marine ecosystems.”

Scientists have already measured significant negative effects on corals and algae in the Gulf of Aqaba, which separates Egypt from Saudi Arabia.

Despite this environmental cost, the expansion of desalination shows no signs of slowing down in almost all regions of a rapidly warming world facing increasing water shortages.

*With reporting by Camilla Veras Mota, BBC News Brasil.